Introduction

New Urbanism Theory

New Neighborhood Cases of Korea

Project overview of Sangam Millenium City

Project overview of Wangsimni New Town

Characterization of New Urbanism in Neighborhood Projects in Korea

Analysis of SMC neighborhood planning

Analysis of Wangsimni neighborhood planning

NU principles in Sangam DMC and Wangsimni neighborhood planning

Conclusions

Introduction

New urbanism (NU) places a major value on the lifestyle and settlement form prevalent in the United States before World War II. NU is a neo-traditional planning movement that seeks to reorganize modern living elements, housing, work, shopping, and leisure space and return to a traditional lifestyle. The movement, which began in the late 1980s, is interested in progressively reorganizing the urban environment and diagnoses various urban etiologies [1]. The cities such as Kentlands, Sea Side, Laguna West, Harbor Town, and Celebration are models of NU design principles. Interest in NU is rapidly increasing, and NU has become a key topic of urban planning [2, 3].

The New Urbanists, with a deep interest in human alienation, class conflict, and environmental issues, came up with the principles of NU to solve these problems. The building up of a community through NU design is the core of social orientation of the movement [4, 5, 6, 7]. New Urbanists presuppose that the paradigm of suburbanization, which began in the mid-20th century, cannot last through the next generation [8]. Instead of the current disordered urban sprawl, compact urban development and infill development that focuses on living factors are used as alternatives. NU emphasizes the neighborhood design marked by mixed-use development of job-housing proximity, pedestrian-friendly urban areas, and a system of wide-open space [9].

This study addresses a gap in the literature, as studies on NU have mostly been conducted in new towns and suburbs [10, 11, 12]. Although there are not many cases of NU inner city renewal have yet been realized worldwide, various NU principles have been reflected in recent inner city renewal projects in Seoul, Korea. This study thus explored the NU design principles present in Sangam Millennium City (SMC) and Wangsimni New Town (WNT), which are representative of Seoul’s neighborhood redevelopment cases, to understand now NU can be applied to urban renewal.

The objectives of this article were to find NU principles of new town in town and to characterize the principles in terms of urban design. The following questions were addressed:

1.How can NU design principles in urban design be classified?

2.How were NU design principles applied in urban development in Seoul?

3.How applicable are NU design principles from an urban design perspective?

New Urbanism Theory

NU emerged in the 1980s as an alternative to conventional suburban developments. Traditional neighborhood development represents a rediscovery of the planning and architectural traditions that shaped some of the most livable communities in America [13]. NU, as a new paradigm of urban design at the end of the 20th century, has been mentioned as a concrete example of a post-modern approach to urban planning [14, 15, 16, 17]. NU focuses on the discussion of concentration and dispersal, as well as the other costs for reducing urban energy consumption and expanding infrastructure [18]; the possibility of reduction of traffic occurrence by efficiency of land use and design substitution [9, 19, 20]; increasing the opportunities for social contact by linking or expanding public space [4, 9, 21]; the preservation of cropland [21]; and better sedentary design [9, 22]. The background for NU can be found in the Ahwahnee Principles, which were established at the Ahwahnee Hotel in Yosemite National Park in 1991. In 1993, the Congress for the New Urbanism was formed and remains active to this day.

New Urbanists presuppose that the paradigm of suburbanization that began in the mid-20th century cannot be sustained through the next generation [8]. Instead of encouraging the current disorderly spread surrounding urban areas, NU is designed as an alternative, with compact urban development that focuses on living factors, infill development, and multi-purpose complexes that bring shopping or work closer to neighboring districts. Emphasis is placed on neighborhood design that fits into the wide-open space system. The NU perspective on the city and suburbanization criticizes land use that separates mutual functions by a considerable distance and prioritizes the use of automobiles, as in the design of widely separated shopping malls, residential areas, and workplaces in box-type industrial parks. This unfortunate increase in traffic, the development of private spaces, shrinking of public spaces, and fragmented green spaces have brought about a change in lifestyle, which is thought to have eroded American values [1, 8, 22, 23, 24, 25]. NU aims to improve quality of life for urban residents and build an urban environment that supports these values; NU regards disordered urban sprawl as the cause of urban pathology. The proliferation of disorderly urban areas is discussed in terms of its social costs, energy consumption, development pressure on agricultural land, public transportation use, efficiency through centralization, changes in development density due to telecommuting, and strengthening the city’s future and city center competitiveness [1, 18, 26].

From the standpoint of urban design, NU can be classified into two types of urbanism: first, the neighborhood pattern that became the prototype of the design from the early settlement period in the United States to the middle of the 20th century, and second, the suburban pattern that has been popular since then. NU seeks to avoid existing forms of urban development and return to a neighborhood-oriented city design; its design tradition is rooted in the City Beautiful and Garden City Movements. NU has also inherited design elements such as the streetcar suburb connected to public transportation, the grid street space and corridors, and the emphasis on public space. Creating a sense of place and grafting a rural lifestyle into the city are keys to NU, as are the importance of green space in the suburbs and the formation of neighborhoods where parks and trails are securely equipped [1]. Specifically, NU is expected to reduce dependence on automobiles and the uncontrolled consumption of land resources by reducing traffic volume; this transit-oriented development (TOD) encourages the use of public transportation such as light rail, pedestrianism, and bicycles rather than passenger cars [9, 23]. NU also seeks to revitalize local economies and regenerate small retail stores in residential areas that are in danger of being extinguished by large discount stores. This ethos is also called neo-traditionalism in that it seeks to reproduce architecturally the design of suburban areas in the United States before World War II [8, 27].

NU seeks a diverse mix of housing types, land uses, and building types and sizes to avoid the uniform and monotonous suburban landscape caused by zoning systems. Creating this built environment is expected to evoke a sense of community by enhancing the sense of unity and intimacy among community residents. This is expected to be an alternative to the overwhelming human alienation prevalent in suburbanization [23]. New Urbanists believe that design should solve social problems from the environmentally deterministic view that design strongly influences human behavior [4, 6, 28, 29, 30, 31].

NU is not about returning to the past, but rather returning to the pre-suburbanization of human consciousness by reducing private spaces and increasing public spaces. This transfer from private to public space can be done by increasing open spaces, placing houses close to the street, reducing land parcel size and building setbacks, and bringing the porch into direct contact with the road [6, 31]. It is estimated that NU principles could make a social contribution through resource allocation, such as by reducing the development cost invested for passenger cars in parking lots and roads and making those savings available to the welfare sector [31, 32].

New Neighborhood Cases of Korea

Project overview of Sangam Millenium City

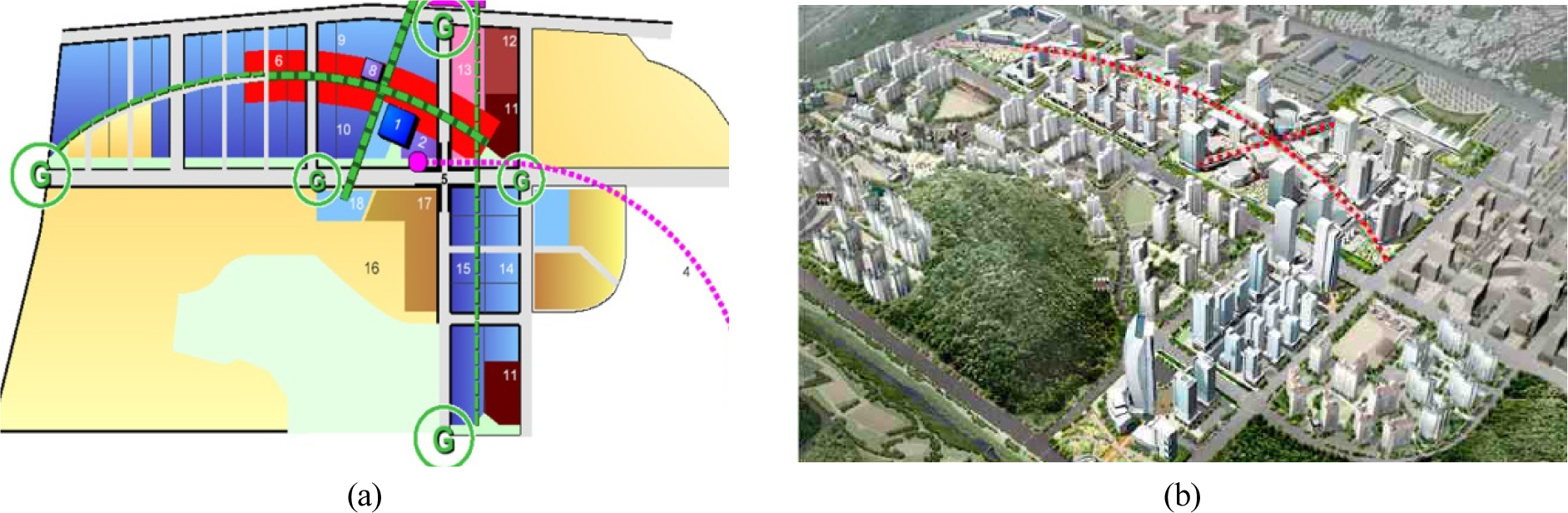

SMC is an example of creating a new city neighborhood where a landfill and clustered settlement were originally located. It is a new neighborhood created around the World Cup Stadium in commemoration of the 2002 World Cup. The master plan was established in 2001 and was planned for a total area of 6,330,000 sq. m, of which the city area—except for the landfill and Han River—was 1,818,000 sq. m. The first phase of SMC was completed in 2011, and the project as a whole is now almost completed. The main land use in the city area (Figure 1) was allocated to residential land (1,270,345 sq. m), commercial land (335,655 sq. m), and road land (212,000 sq. m). The city’s development goals were to be a gateway city, information city, and sustainable city in the metropolitan area.

Gateway city

The concept of the gateway city is to strengthen the character of Seoul and to complete the functions of the city center in connection with wide area access. After the opening of the new airport railroad, the environment of the Susaek Station district which will become the gateway to Seoul’s northwest area was established. It became a connecting point between the Gyeongui Line and Subway Line 6, allowing it to grow as a node of public transportation and a sub-center of Seoul to support the concept of TOD.

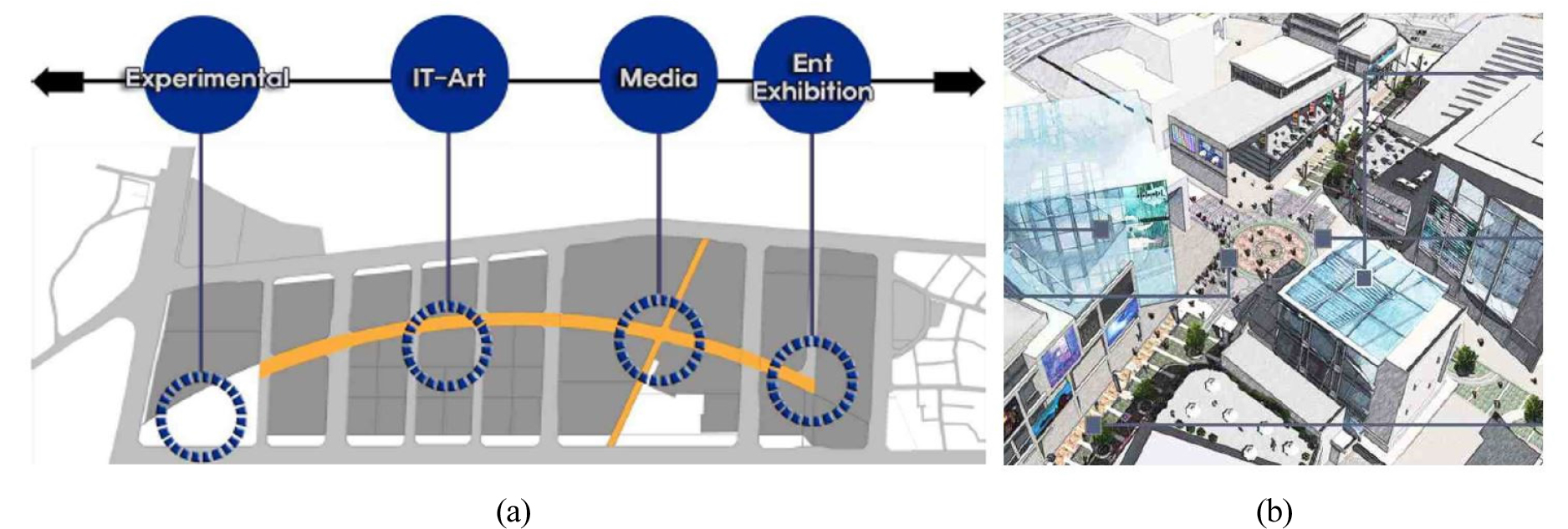

Information city

An information city is a gathering place for high-tech production, exhibition, and sales, and in creating such place, it is necessary to develop the information infrastructure to lead the information age and foster the place as a hub city in the metropolitan area. This fosters the high value-added content and information and communication technologies industries, as well as attempting to combine advanced technology with the design industry to create a high-tech information and multimedia venture industry complex. In connection with the idea of the smart city, common district infrastructure—including water and sewage, electricity, gas pipes, waste collection pipes, air conditioning, and optical communication cables—was installed to save resources and energy.

Sustainable city

The sustainable city planning concept was to restore the environment of Nanjido, an waste landfill, create an ecological park, and create an environmentally friendly city that could save energy and recycle resources, while also establishing a water resource circulation system involving the Han River and surrounding tributaries. This concept solves the environmental problems of landfills including leachate and landfill gas, restores the surrounding ecological environment, and creates the upper and surrounding landfills as a space that can be used by citizens, preserving the natural environment as much as possible, suppressing overcrowded development, and making the most of alternative energy.

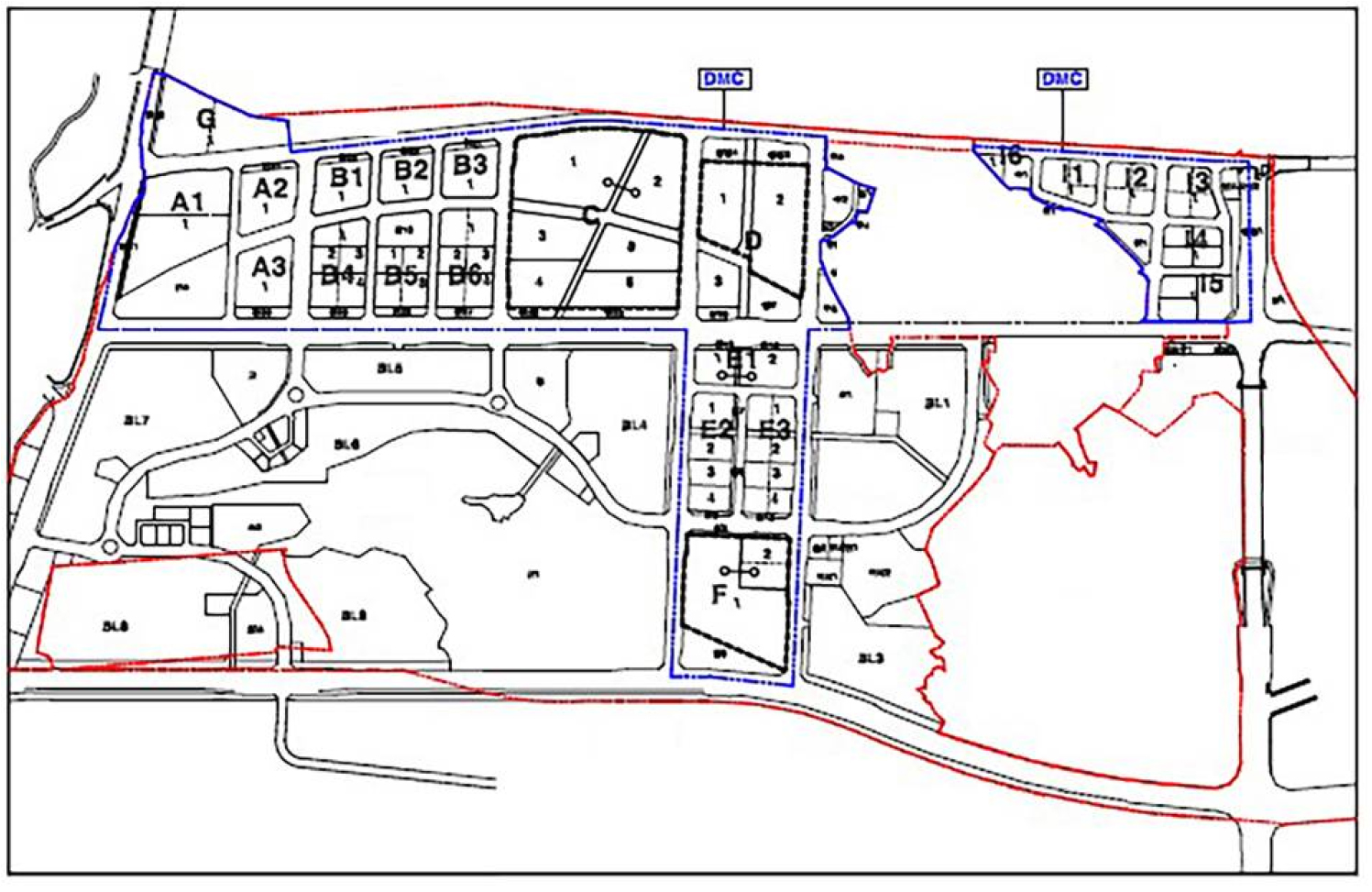

Project overview of Wangsimni New Town

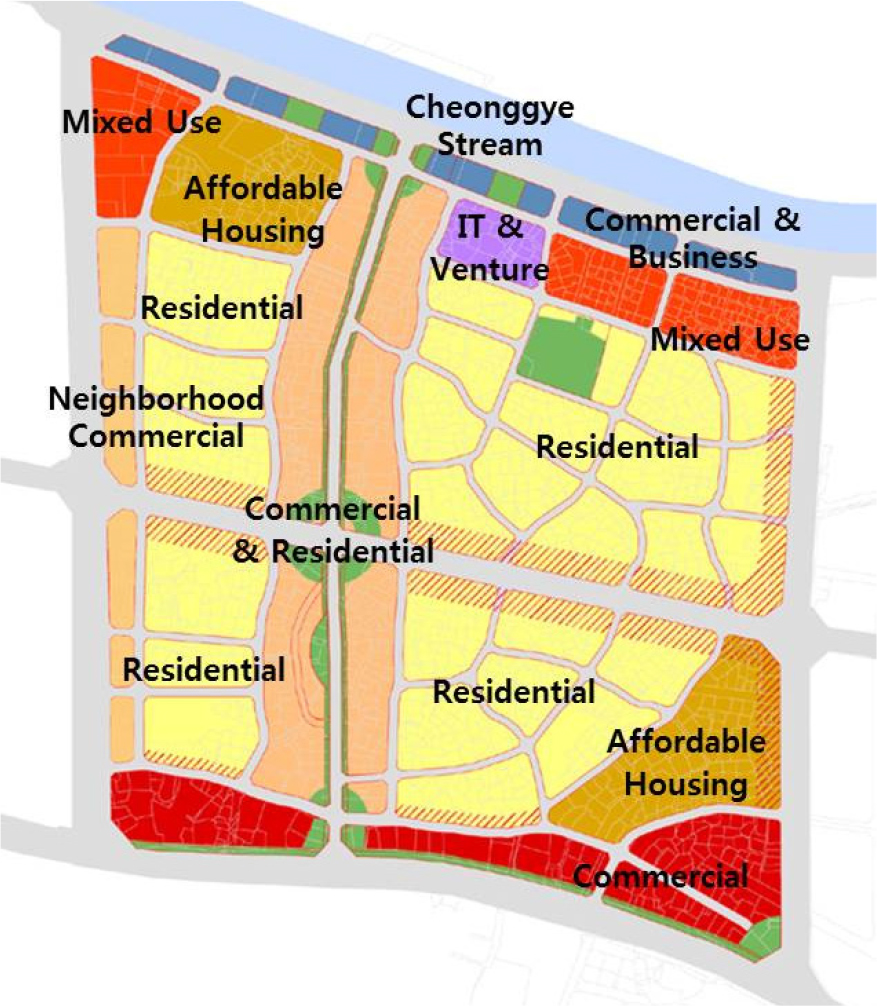

WNT is located on the outskirts of downtown Seoul and is an urban renewal project for small home factories involving foodstuffs and areas with affordable housing. The master plan was established in 2002, with a total area of 335,000 sq. m, of which 211,700 sq. m was for residential land, 45,398 sq. m for commercial land, and 77,902 sq. m for roads and parks (Figure 2). The city’s development goals were to create a compact city with multiple functions, establish a green open space network, and expand public facilities.

Compact city

In the past, manufacturing and affordable housing have been concentrated together and left to stagnate into areas of decline. The plan for neighborhood revitalization tried to create a mixed use development of job-housing proximity to overcome the urban center decline in Seoul and pursued a compact city of high-density development connected with subway stations.

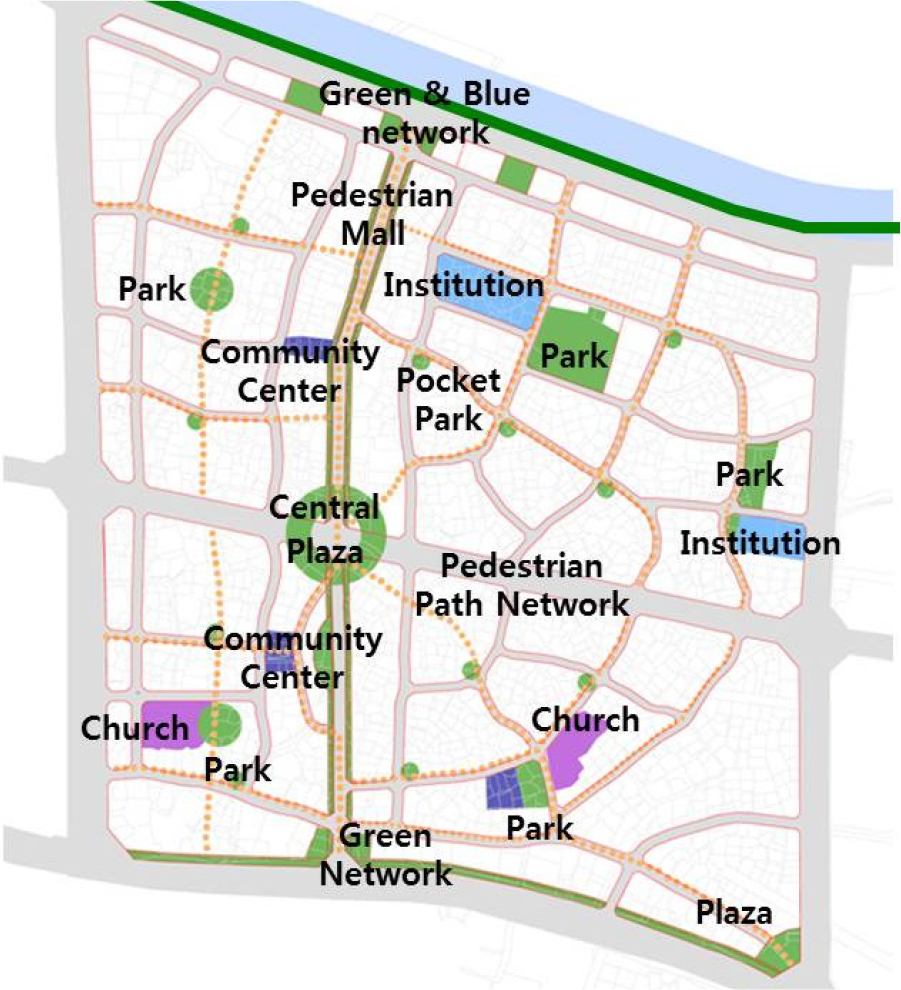

Green open space networking

The green and blue network was expanded by connecting park space and the Cheonggyecheon Stream in the main district. A green road and green axis were created to penetrate the target area, so green spaces would penetrate into each district.

Achieving urban integrity through expansion of community facilities

By expanding educational facilities such as elementary schools and high schools in the center of the city—and intensively establishing community facilities such as sports facilities, libraries, and community centers—the planners intended to support a self-sufficient city that could perform the complete array of urban functions.

Characterization of New Urbanism in Neighborhood Projects in Korea

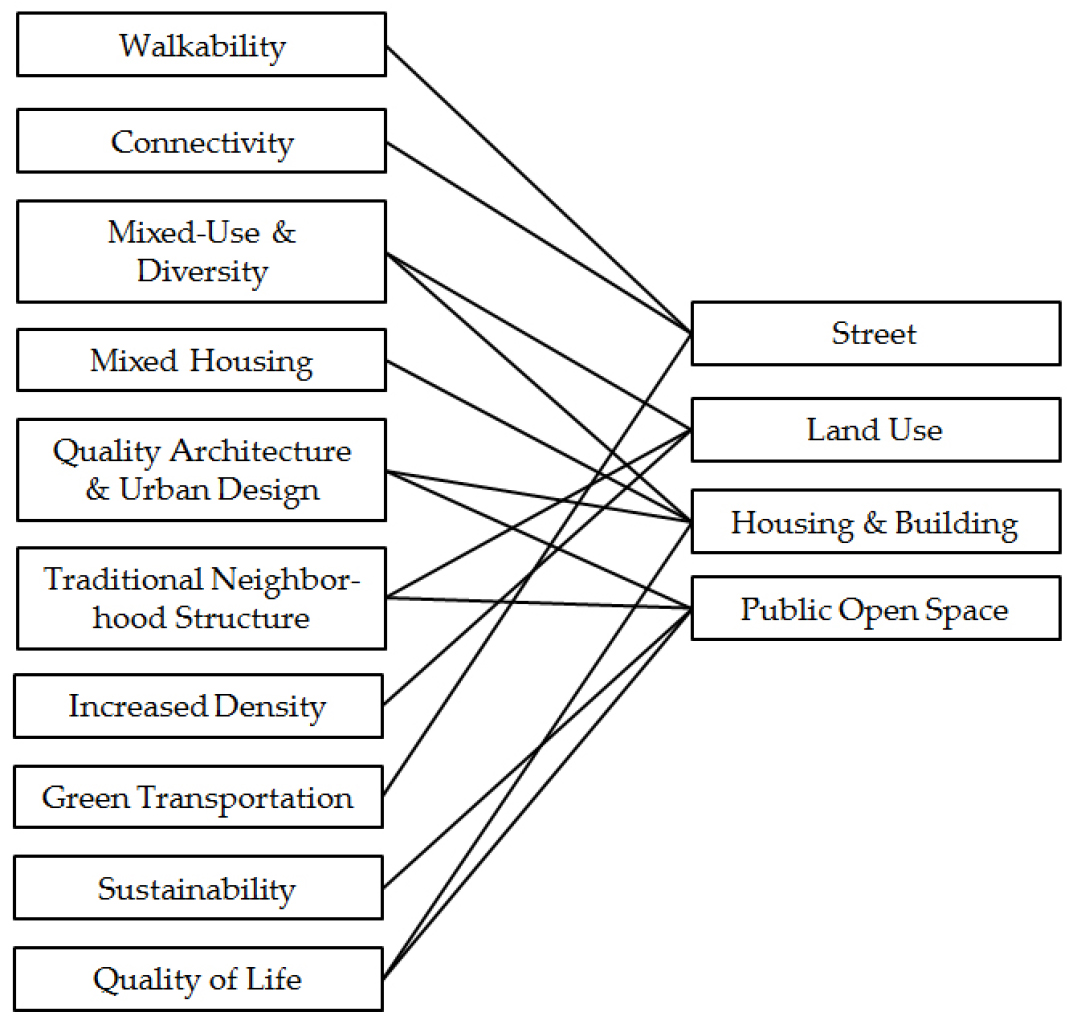

The ten NU design principles are walkability, connectivity, mixed-use and diversity, mixed housing, quality architecture and urban design, traditional neighborhood structure, increased density, green transportation, sustainability, and quality of life [33]. In this study, these ten design principles were classified into four categories for comparative analysis (Figure 3).

Analysis of SMC neighborhood planning

Street

The SMC horizontal network is basically an interconnected street grid network. The main arterial roads penetrate the center to disperse traffic in the district efficiently. Collector and access roads for the arterials in each district secure the hierarchy of the road network. The pedestrian path system adopts a sidewalk parallel and separation method; the footpath is wide, and the bicycle road is also arranged in parallel with the pedestrian road. The sidewalk is thus separated from the driving surface to form a safe and car-free pedestrian pathway. Commercial areas provide a comfortable space for pedestrians with a pedestrian-friendly design. Because the subway station leans to the southeast side and includes a large-scale residential complex, it is difficult to ensure a ten-minute pedestrian commute between home and work, although it is possible by bus. Bus transportation connects the major arterial roads and the major nodes in commercial areas, centering on Susaek Station and Digital Media City Station. Each block in the commercial and residential areas is entered through an underground parking lot, excluding through traffic.

Land use

The center of SMC has a cross-shaped axis centered on Susaek Station, and the central commercial, business, and accommodation centers are concentrated in this space. The boundaries between residential and commercial areas are clearly established. Commercial complexes are also developed by distributing residential complexes at the outskirts of the commercial areas (Figure 4(a)). Shops, apartments, and community facilities are mixed closer together in residential areas for ease of walking within neighborhoods. The commercial business district, where workplaces are concentrated, forms a cross axis to increase accessibility to residential complexes (Figure 4(b)). It is possible to reach the commercial business district from the residential complex within 20 minutes on foot. The central commercial area has the highest floor area ratio (FAR) of 8, while the FAR of the peripheral area is under 5, forming the highest density in the SMC area. The average FAR of the residential areas is 1.8, with high and low density housing being evenly distributed. Institutional facilities are planned closely with residential complexes, allowing for walking commutes.

Housing and buildings

The central commercial district is divided into various block and lot shapes, so the district unit plan guidelines are accordingly diverse, as are the building shapes and volumes. The MBC broadcasting station buildings, which serve as landmarks, are located at the front of Susaek Station to enhance the urban image through architectural diversity and identifiable scenery. Residential areas focus on multi-unit apartments, and a single type of building has been arranged to create a somewhat uniform appearance, but also to reflect the surrounding natural landscape. The design is intended to form a vibrant landscape by co-locating with a unique skyline. A good social mix is encouraged by the construction of various unit types within the block and the placement of both small units and public rental housing (Figure 5).

Public open space

Highly versatile commercial areas provide ample space for pedestrians through public plazas and open spaces linked to pedestrian paths (Figure 6). Pedestrian roads, public plazas, and civic arts in public spaces are well organized, making them excellent for the landscape (Figure 7). Residential areas focus on multi-unit apartments, and all of the residential complex blocks are accessed by underground parking lots, except for minimal aboveground parking, to focus on pedestrian accessibility and rich green open space at street level. The children’s playground and community facilities are located at the center of the residential block to encourage active engagement and interactions among residents in public spaces. The landscape in the block pursues an eco-friendly plan to minimize the environmental impact by incorporating plants that could grow well in the area and conserving the streamlet and wetlands by making use of the existing water-rich environment.

Analysis of Wangsimni neighborhood planning

Street

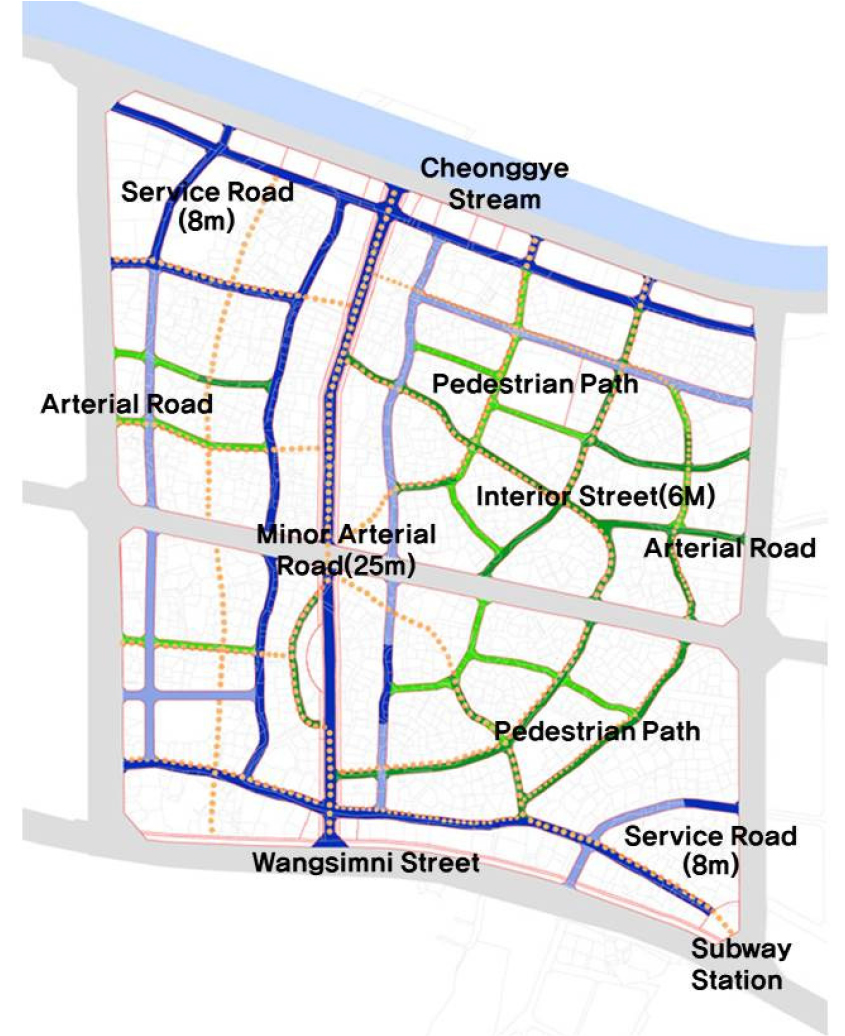

The street network follows a grid pattern, and a side road is planned for the commercial business areas along the main north-south access roads; commercial business facilities are thus accessed from the rear. Residential areas are accessible in each neighborhood through the internal cross axis, which distinguishes the hierarchy between narrow streets, boulevards, and alleys. The pedestrian path system takes a parallel approach for the outer and inner cross axis in the commercial areas and builds a strict pedestrian separation system that circulates through four neighborhoods to form a safe and car-free pedestrian lane (Figure 8). WNT also incorporates a large-scale residential complex, like SMC, which makes it difficult to ensure a ten-minute pedestrian commute. Sangwangsimni Station is part of a transportation network that penetrates the outer and inner cross axes of the target area by bus, and each block in the residential area strictly prevents through traffic from entering through the underground parking lot.

Land use

WNT is a rectangular urban hub centered on Sangwangsimni Station in the southeast of the target area; it is further divided into four large blocks. Commercial and business spaces are located near the subway station, which is characterized by mixed-use development zoning for high-rise multi-use buildings. Cheonggyecheon Stream, at the north of the site, is also allocated for residential, commercial, and business complex facilities. The residential and commercial business mixed-use area is clustered on the south and north sides, with the interior for residential use. Like SMC, community facilities and commercial facilities are mixed with residential areas and placed within walking range. The average FAR of residential areas is under 1.8, and the number of floors is 7 to 25, with high-rise and low-rise buildings distributed throughout. Education facilities and public institutions are placed on a cross axis that separates the area, so pedestrian access is easy from each neighborhood (Figure 9).

Housing and building

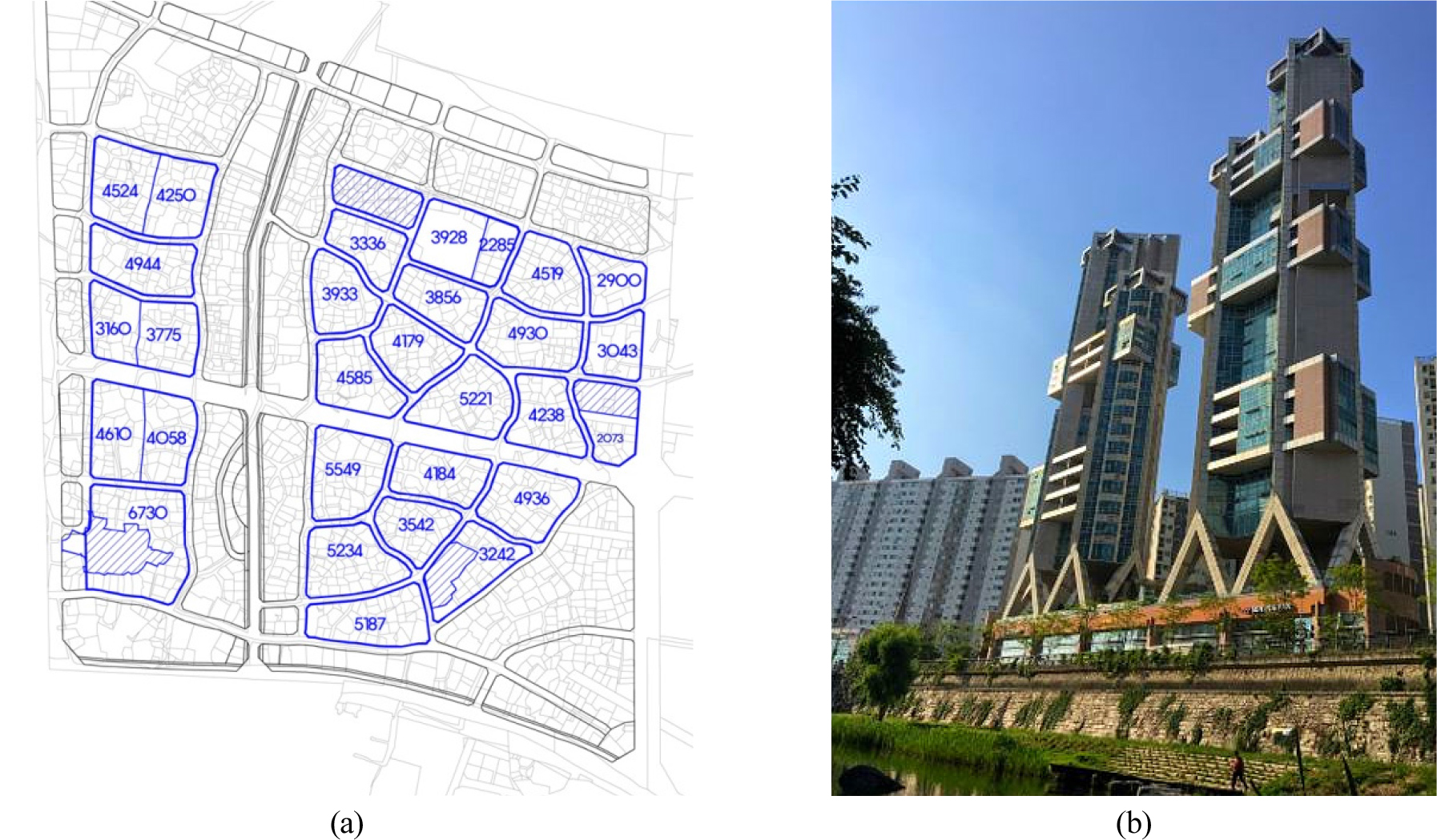

The central commercial district, adjacent to the boulevard, has large blocks that are densely planned around the subway station. The Cheonggyecheon riverside to the north is divided into smaller parcels than the station area and is intended for a combination of residential and commercial buildings as a design landmark to emphasize the riverside landscape (Figure 10(b)). Residential areas incorporate mainly a single building type—multi-family houses—while high-rise buildings along the main road and low-rise buildings toward the inside form an enclosed space. Visual corridors are secured to create a sense of openness from the inside to the outside, so a number of tower types and segmented masses are placed in the outer area. Social mix is encouraged for residential areas through the use of various unit types in blocks, as well as the incorporation of small units and public rental housing.

Public open space

The blocks are not deep in the commercial area, so there is enough pedestrian space on the main road to secure open space, which is located at a main point connected to the interior of the area. Playgrounds and community facilities are intensively arranged in the four neighborhoods through the use of enclosed spaces to improve accessibility and usability by neighborhood residents and ensuring they are well connected with the circular pedestrian axis that penetrates the interior. Residential areas are centered on multi-family housing, and all of the residential complex blocks are entered through underground parking lots, except for some ground parking, so walking and rich green open space are supported at street level. The landscaping in the block is intended to make the most of the existing natural environment by arranging abundant planting spaces and trails and securing a circular green axis that connects to Cheonggyecheon stream in the north (Figure 11).

NU principles in Sangam DMC and Wangsimni neighborhood planning

In both cases, common NU principles were adopted, although some were adopted selectively. A pedestrian-friendly street design and a pedestrian-free walkway were incorporated in both cases, but as they were created as new neighborhoods, it was difficult to realize walkability to reach the goal of a ten-minute pedestrian commute. However, commuting through these areas is very easy because public transportation is well connected. Connectivity is effectively achieved by building a grid street pattern to distribute traffic and ensure ease of walking. By building a road network that connects cities, towns, and neighborhoods, and designing a space that considers pedestrians, the goal was to establish a smart transportation network.

For land use, the commercial center is densely arranged around the subway station, so the center and boundaries are clearly separated. The increased density and traditional neighborhood structure prescribed by the NU design principles are thus pursued. However, in the case of WNT, the traditional neighborhood structure was selectively reflected by placing public space at the subway exits and directly connecting each neighborhood without planning a large-scale public space around the subway station area. SMC distributed residential and commercial complexes in the outskirts of commercial areas, and WNT sought to incorporate mixed use by arranging commercial complexes around the station area and Cheonggyecheon stream.

Diversity of housing and building types was considered in planning the balance of various types of housing, including public rental housing, but true mixed-use was only partially applied for neighboring districts, blocks, and buildings in WNT. Mixed housing was partially reflected in the uniformity in terms of land price around apartment complexes and high density at the city center.

Both cases pursued convenience by arranging public open spaces in residential areas at the center of the district. Plans were ecologically sustainable by fully utilizing planting and existing water systems to minimize environmental impacts and enhance the quality of architecture and urban design. Residential, work, and public spaces thus achieve high quality of life compared to the surrounding areas of urban decline (Table 1).

Table 1.

New urbanism principle characterization of SMC and WNT

| NU principles | Urban design criteria | SMC | WNT |

| Walkability | Street | △1 | △ |

| Connectivity | Street | O2 | O |

| Mixed-use & diversity | Land use Housing & building | O | △ |

| Mixed housing |

Housing & building | △ | △ |

| Quality architecture & urban design | Housing & building Public open space | O | O |

| Traditional neighborhood structure | Land use Public open space | O | △ |

| Increased density | Land use | O | O |

| Green transportation | Street | O | O |

| Sustainability | Public open space | O | O |

| Quality of life | Housing & building Public open space | O | O |

Conclusions

NU is still being incorporated in many new cities since it was first introduced in the late 20th century. This study analyzed how NU design principles were applied by characterizing the cases of urban renewal within existing cities and attempted to interpret these applications from the viewpoint of urban design. The cases of SMC and WNT revealed that ten principles of NU have had a great influence on four urban design factors such as streets, land use, housing and buildings, and public open space in terms of connectivity, quality architecture and urban design, increased density, green transportation, sustainability, and quality of life. These elements are actively being adopted and accepted for streets, land use, housing and buildings, and public open spaces in both new neighborhood cases. Mixed-use and diversity and traditional neighborhood structure are related to land use, housing and buildings, and public open space and were also partially adopted. Although the pedestrian environment in the sites featured a friendly street design and pedestrian paths free from cars, the planned area is large, so it was not possible to ensure walkability and commute on foot. Both cases strengthened public transportation links by connecting to workplaces and make up for the lack of pure walkability. From this overall point of view, NU design principles in urban renewal had positive advantages from planning to realization and can be used as fairly effective principles. This study tried to reveal fundamentals of urban design to adopted NU principles but only two cases were available currently. Hereafter NU still needs to be verified through more cases and established a more substantial theory for urban renewal development as well as new town