Introduction

Literature Review

Social Sustainability, women safety and urban planning

Urban and social theories with focus on gender safety

Research Methodology

Data, Result and Discussions

Conclusions

Introduction

Social sustainability can be defined as a critical facet of the broader concept of sustainable development, which advocates the cohesive way of life among people and communities in a way that is equitable and inclusive. It tries to solve a range of issues like access to basic services, social justice, human rights, and cultural diversity. Within this context, gender safety has emerged as a key area of concern, particularly in urban areas where women and young girls often encounter heightened chances of violence, harassment, and discrimination. Numerous studies have documented the concerns & challenges of women and girls in urban areas, including inadequate access to public amenities, facilities & services like poor lighting and visibility, limited opportunities for social interaction and community engagement. The research studies on the intersectional dynamics of gender safety in urban India, argues that gender-based violence is shaped by multiple factors, including social norms, infrastructure, and institutional practices [1]. These factors can contribute to a sense of insecurity and fear, which can limit mobility patterns of women and their opportunities which ultimately affect their quality of life. A qualitative research with women in Delhi, India by Jagori, concluded that women’s experiences of violence were shaped by factors such as gender norms, lack of public transportation, and inadequate lighting in public spaces [2]. In a similar study by Ramya Subrahmanian and Shilpa Phadke, conducted with women living in slum communities in Mumbai, identified poverty, limited accessibility to services, and the gendered nature of public space as major factors contributing to unsafe gender spaces in urban areas [3].Women often try on their own ways to deal and tackle these factors [4].

To address the above challenges, there is a growing recognition of the need to create gender-inclusive urban environments that prioritize the safety and well-being of all members of the community. This requires a multifaceted approach that involves a greater revamp of physical interventions, such as improved lighting and transportation infrastructure. Recent research has emphasized the importance of taking a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to promoting gender safety in urban areas. For example, a study by [5] sound that community activism and policy interventions can play an important role in addressing gender-based violence in urban communities. Similarly, [6] emphasizes the importance of incorporating gender perspectives into planning and design of public spaces in order to create safer and more inclusive environments for women. Promoting gender safety in urban areas is a critical component of social sustainability, and requires a comprehensive and collaborative approach that involves multiple stakeholders and perspectives. Through this stakeholder participatory approach, women were able to voice their concerns and propose actionable areas to the concerned urban authorities. However, the major challenge is to quantify and create an empirical input framework to identify major parameters and prioritize actions by civil societies, local administration, and public authorities.

In one of the reports, the World Bank emphasized the need for data to inform policies and programs to address the safety concerns of women, including the need for standardized data collection methods and indicators [7].This paper tried to apply the AHP model, which is an analytical approach when the decision is based on multi-criterion. The AHP application is demonstrated in various socially relevant researches and decisions. One such research was conducted in Ulaanbaatar to create a useful framework for evaluating the sustainability of housing programs and ensuring that they meet the needs of residents while minimizing their impact on the environment [8]. The AHP method is used to prioritize the criteria and sub-criteria based on their relative importance, and to identify the most critical planning elements for sustainable urban development [9].

To address the prioritization bottleneck, this paper tried to understand the core urban concepts and amalgamate them with gender studies findings to arrive at major parameters and sub-parameters that are concerned with gender safety. Further the study tried to apply multi criteria decision analysis (MCDA) with the help of 32 relevant stakeholders to create a framework for prioritizing the identified safety parameters. The study was majorly piloted in the city of Kanpur, India, which is undergoing a rapid urbanization and witnessing a rise in concerns pertaining to gender safety. Applying MCDA i.e Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) is very appropriate for gender safety in urban areas because it allows for a systematic and comprehensive approach to identifying and prioritizing the factors that contribute to gender safety in the built environment. The framework tool developed in this study can help planners and policymakers to objectively evaluate the relative importance of various factors that impact gender safety, such as pedestrian mobility, urban amenities, transit system and security. Further this study also proves that AHP can be an effective tool for execution as well in creating gender friendly spaces by concerned authorities.

Literature Review

Social sustainability is one of the key components of urban planning, which primarily focuses on a city or community’s ability in creating and maintaining a socially just, equitable, and livable environment. The aim of social sustainable urbanism is to promote cohesion, community participation, and quality of life, irrespective of their gender, background, income, status etc. The study highlights the need for greater citizen participation and engagement in smart city development, as well as the importance of addressing social inequalities and promoting sustainable development. The findings of the study can be used to guide future smart city development [10].

Urban planners play a significant role in ensuring social sustainability by designing and managing the built environment [11] . They must consider the social implications of their decisions, such as access to basic services, the provision of public spaces, and affordable housing. This section shall review the existing literature pertaining to concepts like social sustainability and gender safety in the context of urban theories and their importance in creating livable and inclusive cities [12]. The study also highlights the importance of citizen participation and engagement in smart city security, as well as the need for interdisciplinary collaboration between security experts, urban planners, and policymakers. The findings of the study can be used to guide future smart city development efforts, particularly in terms of addressing security challenges and promoting citizen- centered security strategies. [13]

Social Sustainability, women safety and urban planning

Social sustainability began to gain essential consideration in urban planning, given the enhanced awareness levels about the social, economic, and environmental challenges faced by cities worldwide. The importance of social sustainability has been recognized by the United Nations (UN) in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which aims to create sustainable and inclusive cities for all [14]. Social sustainability’s importance in urban planning is evident in the impact it has on residents’ quality of life. It also promotes social justice by addressing issues of inequality and discrimination, which can lead to exclusion and marginalization.

Some key aspects of the importance of social sustainability in urban planning include

1.Promoting community participation and engagement: Social sustainability requires that urban planning takes into consideration the needs and interests of all members of the community.

2.Creating livable and inclusive neighborhoods: Urban planning can help create livable and inclusive neighborhoods that provide safe and accessible public spaces, affordable housing, and access to essential services such as healthcare, education, and transportation.

3.Encouraging social cohesion and cultural diversity: Urban planning can encourage social cohesion and cultural diversity by creating spaces that facilitate social interactions and promote cultural exchange. This can help build a sense of community and strengthen social ties.

4.Addressing social inequalities and environmental justice: Urban planning can address social inequalities and promote environmental justice by ensuring that planning decisions are made in a way that promotes equity and fairness.

Urbanism plays a crucial role in influencing the experiences of women in cities. Women face unique challenges and opportunities in urban environments, and urban planners and designers must take these into account to create women-friendly cities. This literature review will examine key themes in gender studies and urbanism research related to making cities more women-friendly [15]. Safety and security are essential components of a women-friendly city. Women are more prone to and exposed to harassment and violence in public spaces, and urbanism can play a significant role in addressing these issues. Research shows that measures such as improved lighting, increased police presence, and more active public spaces can help reduce crime and improve safety [16]. However, safety and security measures must be carefully designed to avoid creating exclusive or oppressive environments that restrict women’s mobility and freedom [17]. These insights take us to explore the fundamental concepts of crime prevention, natural surveillance, and safety perception as important aspects to understand, using the well-acclaimed concepts from the fields of social sciences and urban design. In this regard, gender studies is an interdisciplinary field of study that explores the social construction and performance of gender in society. It involves examining the ways in which gender shapes our identities, behaviors, and experiences, as well as the social and political structures that reinforce gender inequality. As summarized in the Table 1, This literature review will provide an overview of key theories and concepts that have a fusion of gender and urban studies.

Table 1.

Literature review of Gender theories [1961-2018]

| Year | Theory | Inference | Reference | Key components discussed |

| 1961 |

Eyes On Street |

The inference of the Eyes on the Street theory is that urban environment’s design and physical layout can have a significant impact on levels of safety and social cohesion. The theory emphasizes the importance of natural surveillance as a means of deterring criminal activity and promoting community engagement. | [21] |

1. Active street frontages 2. Mixed-use developments 3. Clear sightlines 4. Lighting 5. Community engagement: 6. Greenery 7. Walkability 8. Pedestrian-friendly streets |

| 1970 |

Situational Crime Prevention |

Situational Crime Prevention theory focuses on reducing opportunities for crime through modifying the environment and increasing the perceived risk of detection. It focuses on specific situations, like reducing opportunities for crime through measures such as increased surveillance and changing the layout of the environment. | [24] |

1. Opportunity reduction 2. Specificity 3. Rational choice theory 4. Displacement 5. Evaluation |

| 1971 |

CPTED Theory- |

CPTED theory discusses that design and physical environment can influence fear of crime and levels of crime. The 4 principles of this theory are natural surveillance, access control, territoriality, and maintenance | [27] |

1.Natural Surveillance, 2. Territoriality, 3. Access Control, 4. Maintenance. |

| 1972 |

Defensible space |

Defensible Space theory proposes that a well-designed physical environment can deter crime and increase community safety by providing clear boundaries and territorial control. | [28] |

1.Territoriality 2.Natural Surveillance 3. Image and Maintenance 4. landscapes 5. Graffiti 6. Physical Barriers 7. Access Control |

| 1980 |

Gendered Space Theory |

Gendered Space Theory is a feminist urban theory that examines the relationship between gender, space, and power in the production and experience of urban environments. | [29] |

1. Spatial segregation 2. Fear of crime 3. Masculinization of public space 4. Patriarchal power relations 5. Gendered norms and expectations |

| 2011 |

CPTED Theory- |

CPTED theory has continued to evolve and gain relevance over the past three decades. Overall, the paper underscores the ongoing importance of CPTED theory as a framework for designing and managing the built environment in ways that promote safety, social cohesion, and quality of life. | [30] |

1. Inclusivity 2. Sustainability 3.Environmentally-friendly built environments 4. Technology 5. Human Behavior |

| 2018 |

Towards an Urban Theory of Care |

The theory proposes an urban theory of care that seeks to highlight the spatial and social dimensions of care provision, and to promote a more holistic approach to urban planning and design that takes into account the needs of caregivers and care recipients. | [31] |

1. Interdependency 2.Inclusive and participatory planning 3.Supportive infrastructure 4. Care work and care workers 5. Ethics of care |

Urban and social theories with focus on gender safety

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) has been a popular multidisciplinary applicable approach that aims to improve safety and reduce crime in urban environments. This approach emphasizes design and how to manage physical and social environments to deter criminal activity and enhance the perception of safety among residents and visitors. CPTED has been widely adopted by urban planners, architects, law enforcement agencies, and community organizations as a practical tool for enhancing public safety [18]. Several studies have evaluated the effectiveness of these approach strategies in improving safety and reducing crime in urban areas. One study by Jeffrey Nassau and Jeffrey LaFrance (2014) examined the impact of the approach on crime rates in 13 cities in the United States. This study found that the implementation of CPTED principles led to a reduction in crime in 10 of the 13 cities, with a median crime reduction of 10%. However, some studies have also raised concerns about the potential for CPTED strategies to displace crime rather than prevent it. For example, a study by Elizabeth Groff [19] found that the implementation of CPTED strategies in one area of Philadelphia led to a displacement of crime to nearby areas that were not targeted by CPTED measures. Despite these concerns, CPTED remains a popular and effective approach to improving safety and reducing crime in urban environments. By considering the design and management of physical and social environments, CPTED can help create safer and more livable cities for all residents and visitors [20]. The “Eyes on the Street” theory is a well-known concept in the field of design and urban planning that was introduced by Jane Jacobs in her most popular book from 1961 [21]. The theory suggests that the presence of people on the street, particularly those who live and work in the area, can contribute to increased safety and vitality in urban neighborhoods [22]. Over the years, there have been numerous studies and discussions on the effectiveness of the “Eyes on the Street” theory in creating safer and more vibrant urban environments. One of the key findings is that the presence of eyes on the street is associated with reduced crime rates, as it increases the likelihood of potential perpetrators being observed and held accountable by others in the area. The “Eyes on the Street” theory remains a prominent concept in urban planning and design, and continues to be studied and debated by scholars, practitioners, and community members alike as a key component of creating safe and vibrant urban environments.

Defensible Space theory, proposed by architect and planner Oscar Newman in 1972 [23], defines the relationship between crime prevention and the physical environment. According to Newman, the built environment’s design can significantly impact crime rates, and certain features can help create a sense of ownership and territoriality among residents that deters crime. Newman’s work has contributed to a broader understanding of the importance of the built environment in shaping social behavior and crime rates, and his ideas continue to be influential in contemporary urban design and planning [23].

The concept of Situational Crime Prevention (SCP) is another urban theory that addresses safety parameters. SCP theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the specific context and circumstances that contribute to criminal activities in urban spaces. By removing the opportunities for criminal activities, crime can be prevented through modifying the environment, such as by improving lighting, removing physical barriers, or creating more formal surveillance systems [24].

The Gestalt Theory, also known as Gestalt psychology, is a theory of perception developed in the early 20th century. The term “Gestalt” is a German word that means “shape” or “form,” and the theory emphasizes the importance of how we perceive and organize visual information into meaningful patterns and wholes. The visual quality of the built environment is a significant determinant of perceived safety and, by extension, women’s mobility and access to resources [25].

Smart cities improve the quality of life by using technology to create more efficient and sustainable systems in urban environments. One aspect of smart cities is integrating technology into urban planning and management to increase safety and security, particularly for women. Technology can be used to improve lighting in public spaces, increase the visibility of public areas, and monitor potential threats. This can include the use of smart lighting systems that adjust brightness based on the time of day, the use of cameras and sensors to detect potential hazards, and the use of mobile apps that allow women to quickly and easily report incidents of harassment or violence. Jaemin Lee emphasizes the importance of creating a pleasant and safe environment for people to walk, shop, and socialize using technology, which can play a vital role in achieving and enabling a more efficient and personalized experience for pedestrians. [26]

Research Methodology

Thomas Satty developed the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), which is a very popular multi-criteria decision-making methodological model. According to the model, the approach is highly structured for handling complex problems with multiple criteria and systematically prioritizes and evaluates them. The AHP process breaks down the complex issue or problem into small, manageable parts and then assesses these parts based on their relative importance and how well they contribute to the overall goal. This is accomplished through a pairwise comparison process, where the decision-maker compares each criterion or option against every other criterion or option in terms of importance or performance.

To evaluate the significance of each component at a given stage, a pairwise comparison is made between the component and the next higher-level component. This process starts at the top and proceeds downward in a hierarchical manner. By performing these pairwise comparisons at each level, a set of square matrices can be obtained, which reduces the complexity of the decision-making process.

A = [αij]n×n as in below [32]

()

The properties of the matrix, which involve reciprocal relationships, are explained in the following section [33].

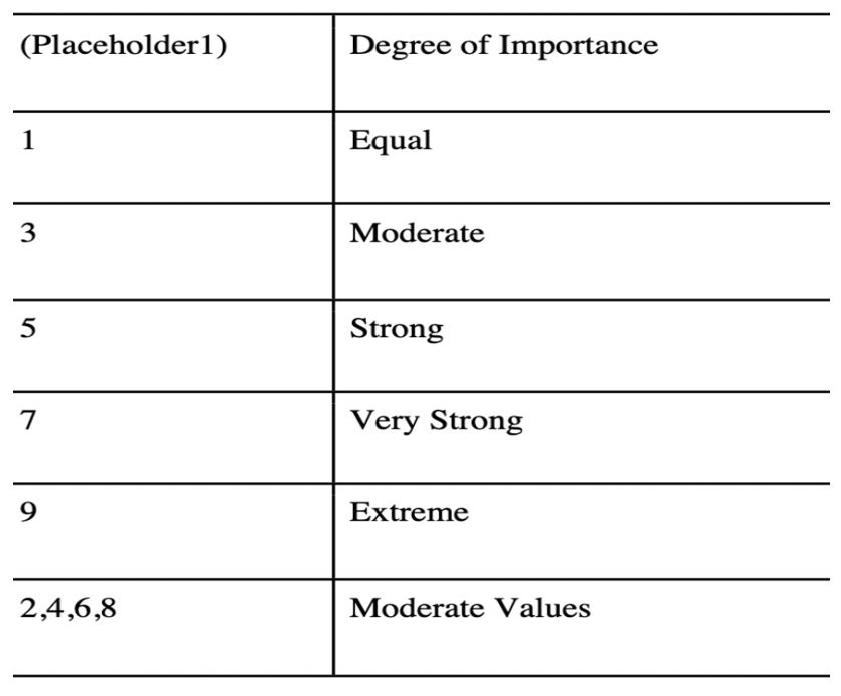

The process of assigning weights to the items in pairwise comparison is conducted using a scale ranging from 1 to 9. Once all of the pairwise comparison matrices [W1, W2, ……, Wn] [34] have been created, the weight vector is computed using Satty’s eigenvector technique. This method comprises two steps: creating pairwise comparison matrices and computing weights [35].

For all I =1, 2,.....,n

As shown in equation 3, Satty established the connection between the pairwise comparison matrix A and the vector weights [36].

The λmax value plays a vital role in AHP and is used as a reference point for filtering data through the calculation of the Consistency Ratio (CR) of the estimated vector. To determine the Consistency Index (CI) of any matrix, Equation 4 can be applied.

Eq. 5 used to analyzed CR: [37]

Satty’s research presents Table 2, which displays the values of the random consistency index (RI) obtained from a randomly created pairwise comparison matrix. The acceptability of the comparisons is determined based on the Consistency Ratio (CR), where a CR below 0.1 is considered acceptable. In case the CR exceeds 0.1, it indicates conflicting evaluations, and Satty recommends reconsidering and revising the key parameters in the pairwise comparison matrix [38].

Table 2.

Random inconsistency indices (RI)

| N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| RI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 0.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.46 | 1.49 |

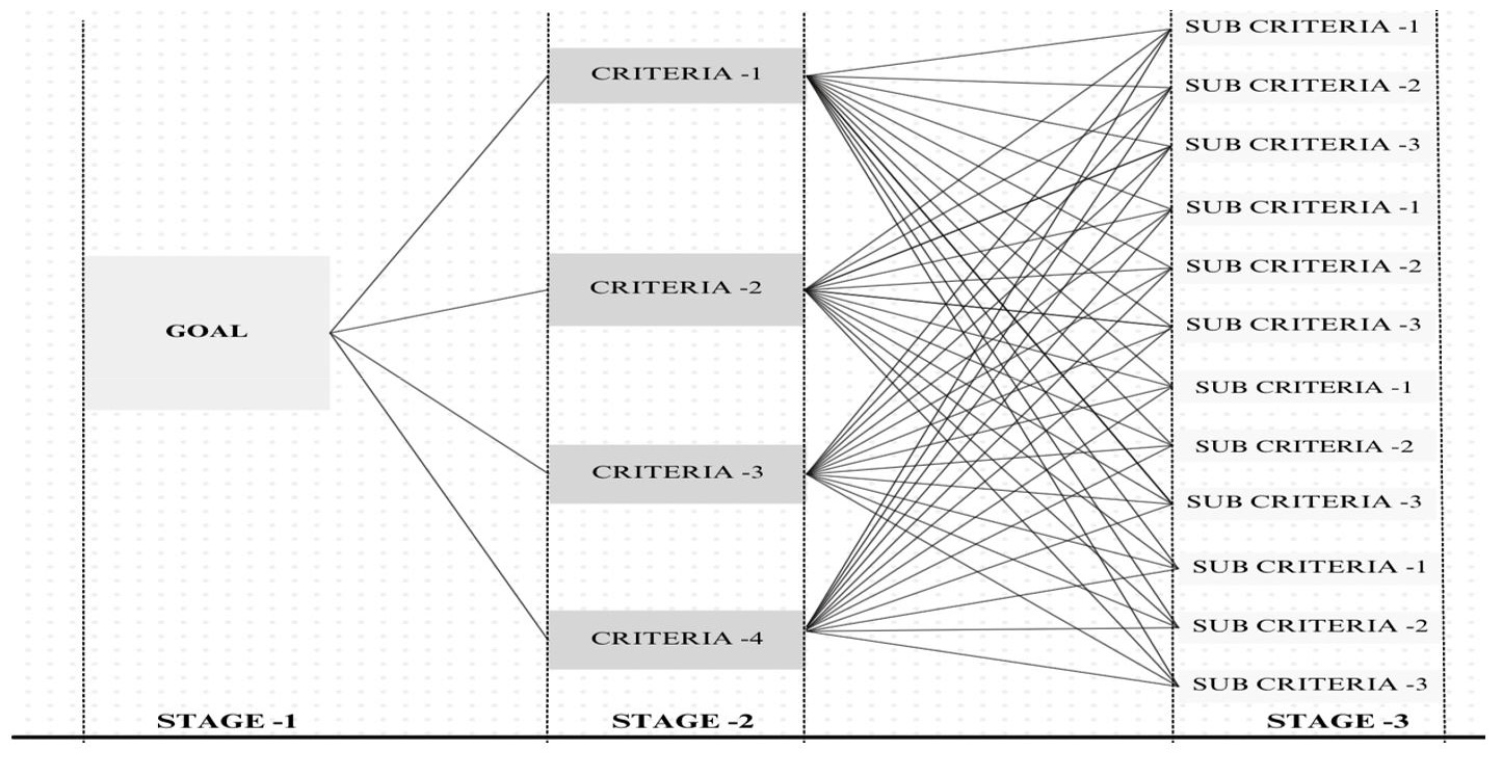

The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) consists of a three-step process. Step 1 involves establishing the research goal by defining specific criteria. Step 2 entails defining criteria by breaking them down into sub-criteria. Step 3 involves defining the parameters and variables for the sub-criteria. In the evaluation of gender-friendly urban space design, a multitude of elements are involved in achieving an effective strategy. This process utilizes Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA), with the AHP being implemented in this analysis.

As shown in the Figure 2, The evaluation of this research involves several steps, including:

·Stage 1: Providing an overview of the topic and research area

·Stage 2: Identifying the indicators and criteria

·Stage 3: Determining the criteria & sub-criteria

·Stage 4: Conducting pairwise comparisons

·Stage 5: Assigning weights

·Stage 6: Normalizing weights

·Stage 7: Assigning final scores

Once all of the criteria have been analyzed and structured in a clear hierarchical manner, it is now appropriate to proceed to the subsequent stage of AHP to achieve the objectives of this paper.

Data, Result and Discussions

To apply the AHP model, as discussed in the above research methodology, this study piloted the application in the city of Kanpur, India. Kanpur is one of India’s major cities with a population of 2.7 million and is divided into 6 administrative zones. The city is witnessing an increasing trend in women’s safety- related cases, and local authorities are taking steps to address this issue. This study has been piloted to complement the efforts of policymakers and local bodies in prioritizing actionable areas.

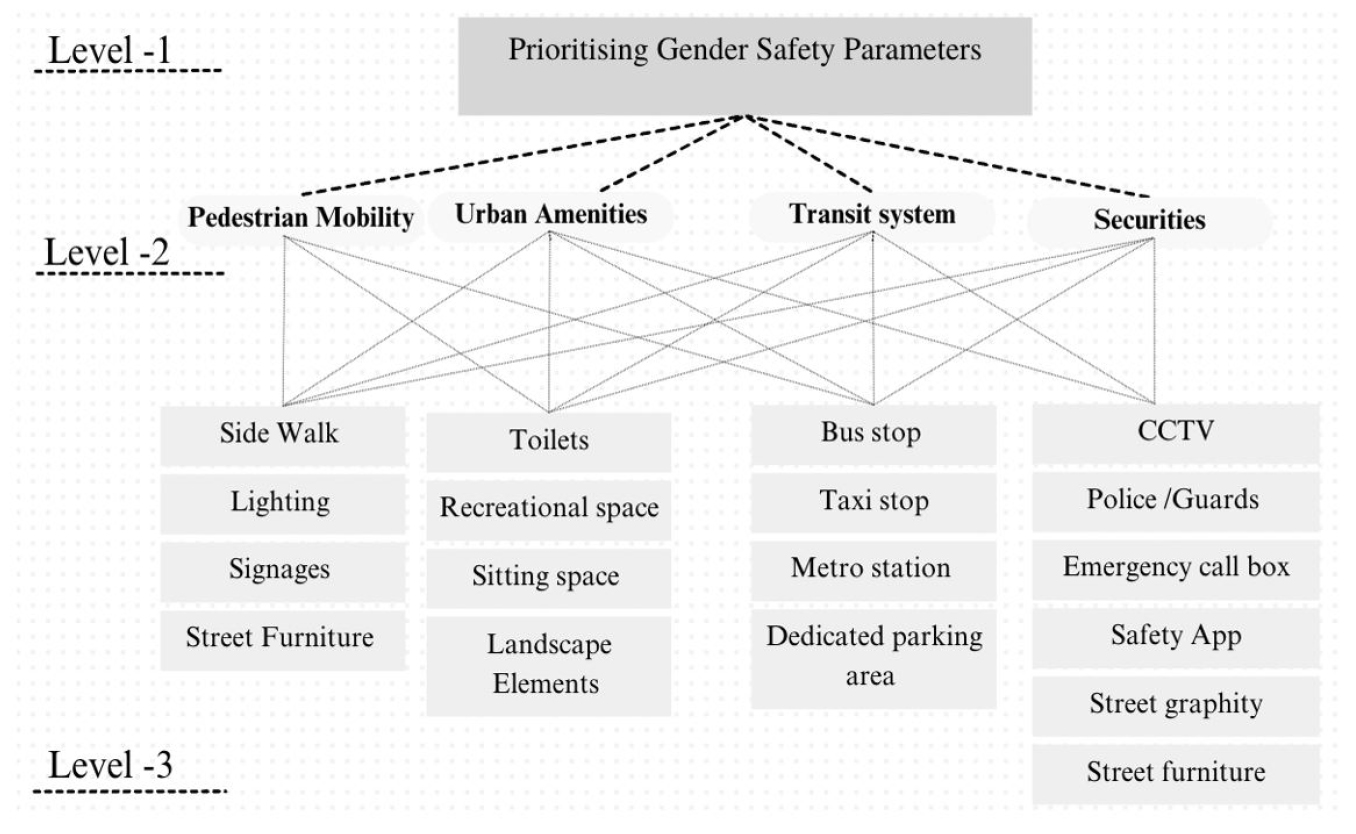

The pilot study involved 32 relevant stakeholders in identifying the main criteria and sub-criteria using a set of questionnaires circulated among them. These criteria and sub-criteria were then assigned their respective relative weights. The four main criteria identified are Pedestrian Mobility, Urban Amenities, Transit System, and Security System, all essential aspects for ensuring women’s safety in urban spaces. Additionally, the research aimed to implement a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach to establish a structure for prioritizing the identified safety parameters. The study utilized the row geometric mean method for all the analyses, which proved to be a precise approach in dealing with complex scenarios involving multiple criteria for decision- making (MCDM) [29].

The study revealed that people’s perceptions of urban spaces varied based on certain aspects, ranging from feeling the least safe to feeling the safest, or from agreeing to disagreeing on certain factors. Women often feel unsafe in urban spaces. Research has identified several factors that affect women’s movements in cities, including Pedestrian Mobility, Urban Amenities, Transit System, and Security.

Specific factors related to Pedestrian Mobility can make an urban space more women-friendly, such as the presence of sidewalks, adequate lighting, appropriate signage, and street furniture (as shown in Figure 3).

In addition to pedestrian mobility and urban amenities, transit systems and security are also important factors that contribute to creating a woman-friendly urban space. For pedestrian mobility, factors such as sidewalks, lighting, signages, and street furniture are crucial. For urban amenities, toilets, recreational spaces, sitting areas, and landscape elements are important. The transit system, on the other hand, should have bus stops, taxi stands, dedicated parking areas, and metro stations, as indicated in Table 7. Lastly, security measures such as CCTV, police/ guards, emergency call boxes, safety apps, street graffiti, and street furniture also play a significant role in making urban spaces safer for women.

After identifying all criteria and the respective sub-criteria, the researcher conducted the pairwise matrix comparison constructed on experts’ comprehension regarding the relationship between the identified parameters and the research’s criteria and sub-criteria. The row geometric mean approach was then used to assess the safety concerns of women in urban areas. The pairwise comparison matrices, consistency checks, and relative weights of all the criteria and sub-criteria are presented in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Table 3.

Comparison of 4 Main criteria

| PM | UA | TS | SS | CW | |

| PM-1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2.990 |

| UA-2 | 0.2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1.046 |

| TS-3 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 0.707 |

| SS-4 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.451 |

PM-1: Pedestrian Mobility, UA-2: Urban Amenities, TS-3: Transit System, SS-4: Securities, CW: Criteria Weight

·CR= 0.07

·CI= 0.04

·RI= 0.9

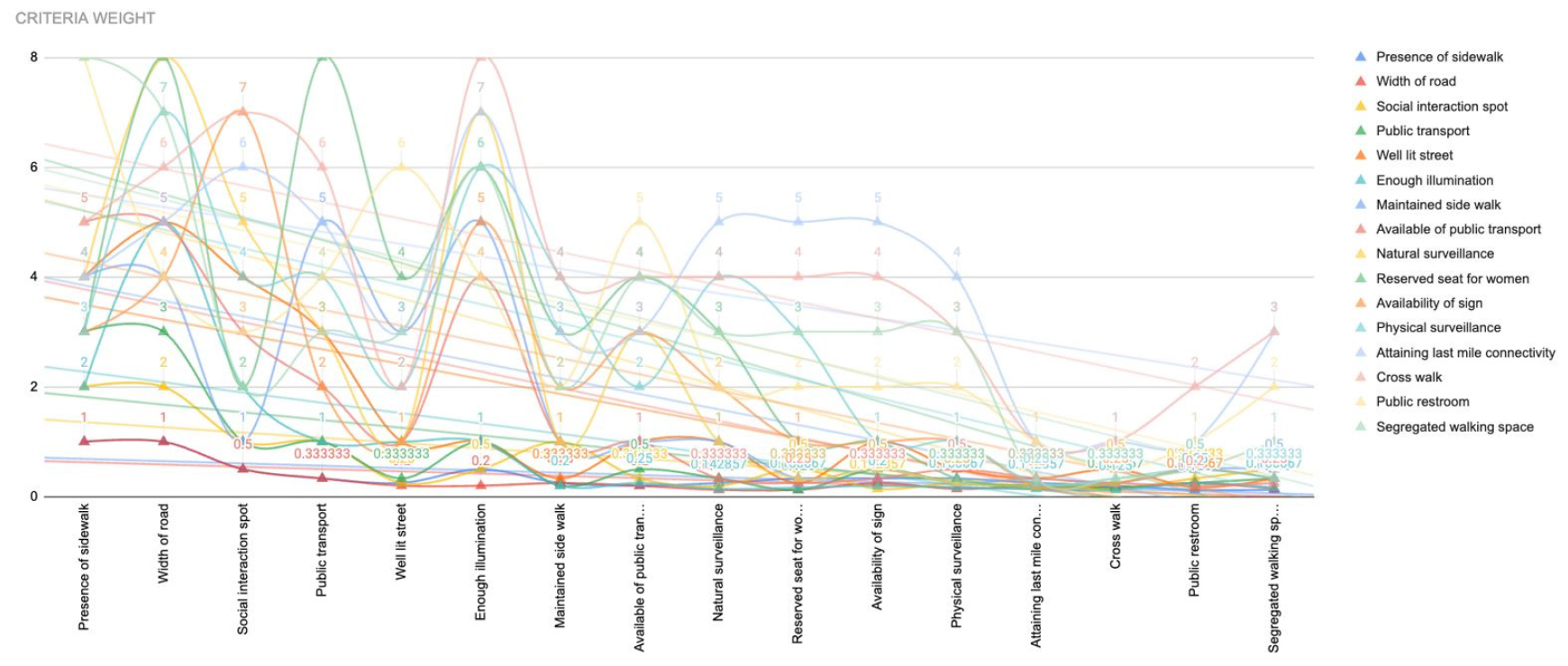

The pairwise comparison was shown for these 4 main criteria: PM-1, UA-2, TS-3, SS-4. The degree of importance of each criterion relative to others is represented in the Figure 1. The values in the table indicate the degree of importance. The CR (Consistency Ratio) of this matrix is 0.07, which is below the acceptable threshold of 0.1, indicating that the judgments made in the pairwise comparisons are consistent and reliable. The CI (Consistency Index) for this matrix is 0.04, and the RI (Random Index) is 0.9.

Hence, the AHP technique involved the use of paired comparisons of sub-criteria on an equal scale. A paired scale was selected for each criterion to facilitate the comparisons. This process led to the creation of comparison matrices for each of the criteria - PM-1, UA-2, TS-3, SS-4, as demonstrated in Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Table 4.

Pair wise comparison of sub criteria Pedestrian Mobility

| PM-1 | SW | LT | SG | SF | CW | |

| SW | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.340 | |

| LT | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1.778 | |

| SG | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 3 | 0.447 | |

| SF | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.537 |

PM: Pedestrian mobility, SW: Sidewalk, LT: Lighting, SG: Signages, SF: Street Furniture

·CR= 0.05

·CI= 0.04

·RI= 0.9

Table 5.

Pair wise comparison of sub criteria Urban Amenities

| UA-2 | T | RS | SS | LE | CW | |

| T | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3.162 | |

| RS | 0.2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1.046 | |

| SS | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 2 | 0.707 | |

| LE | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.427 |

UA: Urban Amenities, T: Toilets: RS: Recreational space, SS: Sitting space, LE: Landscape

·CR=0.05

·CI=0.04

·RI=0.9

Table 6.

Pair wise comparison of sub criteria Transit system

| TS-3 | BS | TS | MS | DPA | CW | |

| BS | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2.990 | |

| TS | 0.25 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1.106 | |

| MS | 0.2 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 0.668 | |

| DPA | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.451 |

TS: Transit system, BS: Bus stop, TS: Taxi stop, DPA: Dedicated parking area

·CR=0.054

·CI=0.049

·RI=0.9

Table 7.

Pair wise comparison of sub criteria Securities

| SS-4 | CCTV | P/G | ECB | S A | S G | SF | CW | |

| CCTV | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3.140 | |

| P/G | 0.25 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1.762 | |

| ECB | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1.037 | |

| S A | 0.2 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.818 | |

| S G | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 0.693 | |

| SF | 0.25 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.306 |

SS: Securities, P/G: Police /Guards, ECB: Emergency call box, SA: Safety App, SG: Street Graffiti, SF: Street furniture

·CR=0.09

·CI=0.112

·RI=1.24

The above Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7 represent the pairwise comparison matrices of sub-criteria under the 4 main criteria, namely PM-1, UA-2, TS-3, SS-4. The Consistency Ratio (CR) for each comparison matrix is 0.05, 0.0547, 0.0547, and 0.0906, respectively, for Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7. All of these values are lower than the threshold value of 0.1, indicating that the comparison matrices are acceptable, consistent, and reliable. The Consistency Index (CI) values are 0.0497, 0.0492, 0.0492, and 0.1124, respectively, which are also within an acceptable range, with RI values of 0.9, 0.9, 0.9, and 1.24, respectively.

The above Table 8 explains the decision-making framework or prioritization matrix. It consists of several criteria, sub-criteria, weights, normalized criteria, and ranks. The first column shows the criteria and sub- criteria. The second column shows the weight of each criterion. The third column shows the weight of each sub-criterion. The fourth column shows the normalized value of each criterion, which is calculated by multiplying the weight of the criterion and the weight of the sub-criterion. The last column shows the rank of each sub-criterion based on its normalized value.

Table 8.

Pair wise comparison of sub-criteria with weight consistency check

The Table 9 represents a prioritized list of sections based on their priorities, ranks, and positive and negative factors. The third column shows the rank of each section, where the section with the highest priority is ranked first. The fifth column shows the negative factor, which could be a decrease in priority due to some negative attribute or issue. In this table, the negative factor is represented as a percentage. The first row represents section 1, which has a priority of 50.70%, making it the highest-priority section. It also has a rank of 1, indicating that it is ranked first. The positive and negative factors for this section are both 3.70%.

Conclusions

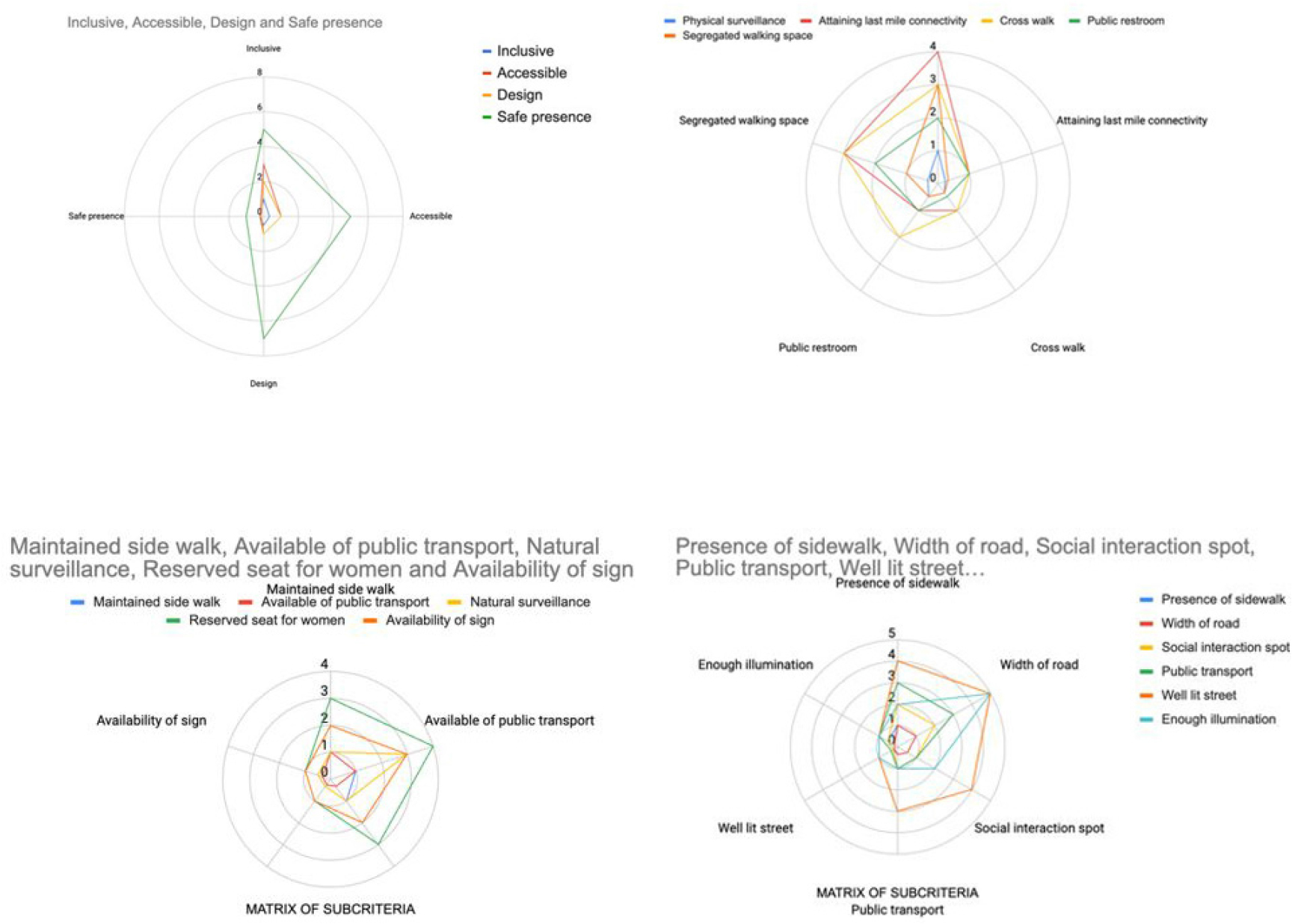

In conclusion, this study demonstrated how the AHP model can be applied to create a Prioritization Framework Tool (PFT) for enhancing gender safety in the city of Kanpur, India. As shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, the framework is also represented graphically using line diagram and radar charts. The study identified pedestrian mobility, urban amenities, transit systems, and security systems as key parameters for ensuring women’s safety in urban areas. Among these parameters, pedestrian mobility was found to be the most critical factor in providing a sense of safety for women. The study also highlighted the need for research capacities and networks within local communities to develop women-friendly cities through participatory planning. By assigning weights to indicators and employing AHP, diverse perspectives can be taken into account, thereby enhancing public participation in urban decision-making. The study’s findings, such as PFT, can help policymakers and urban planners in Kanpur prioritize and allocate resources to improve women’s safety in urban areas. While Table 9 provides broader areas to act upon, Table 8 offers a useful framework as a starting point for prioritizing gender safety parameters. In short, rankings derived using AHP can serve as a Prioritization Framework Tool (PFT) to achieve gender safety.

Overall, this study contributes to the broader goal of social sustainable urbanism, which aims to create inclusive, safe, and equitable urban spaces for all. By prioritizing gender safety parameters, cities can create more livable environments that promote social change and improve the quality of life, especially for women. This paper focuses on the inclusion of women in the urban planning process and highlights the significance of participatory planning as a tool for promoting social change. It recognizes that women’s voices often need to be amplified and that they might not be fully represented in the decision-making processes of such a crucial endeavor. In this regard, AHP is not only a great solution for creating a prioritization framework tool but also enables participatory planning to achieve socially sustainable urbanism.