Introduction

The Environment as a Polarized Issue

Political Trust, Ideology, and Environmental Spending

Measurement

Data

Variables

Results

Discussion

Introduction

Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ (1962) inspired the modern environmental movement which blossomed until the early 1970s [1, 2]. During this brief window of opportunity, the environmentalists garnered enthusiastic support from both liberals and conservatives [3]. Political leaders began to pay attention to how human greed and technology were affecting the environment [3]. The Nixon administration saw environmentalism as an opportunity to impress voters and created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and passed bills to protect the environment. These include, the National Environmental Policy Act (1969), the Clean Air Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), the Endangered Species Act and the Safe Drinking Act (1974) [4].

However, views on environmental issues have recently become polarized. For example, the Trump administration introduced one deregulatory measure after another [5, 6], which affects the offshore drilling of oil to pipelines, the national monument, and coal power [7, 8, 9]. In addition, a significant number of high-ranking officials and veteran scientists have left or been ousted from the EPA [10]. Moreover, Scott Pruitt, the first EPA administrator in the Trump administration has been implicated in a series of financial and conflict-of-interest scandals and was forced to resign in July 2018. The administration has mocked efforts to mitigate climate change [10, 11, 12]. Disdained as fake science, climate change and related environmental spending has undergone some harsh budget cuts in recent years (Davenport and Lipton, 2017). Consequently, conservatives have become fixated on the environment and it has become an issue that differentiates conservatives from liberals.

This study refers to ‘political trust’ as a mechanism that can bring liberals and conservatives together in their support for environmental spending. Scholars claim that citizens are more likely to support government programs when they possess a high degree of political trust [13, 14]. Studies show that political trust can moderate the relationship between ideology and attitudes to policy [15, 16]. With increased political trust, liberals are more inclined to support conservative agendas including tax cuts and social security privatization and conservatives are more likely to support liberal causes such as social welfare and other redistributive government programs [13, 14, 15, 16]. As such, some scholars have dubbed political trust a ‘decision heuristic’ whereby citizens express their willingness to support government programs that present distinct ideological risks to them, if moderated by political trust [15].

When the environmental agenda began to impose ideological risks to conservatives, political trust served as a mechanism to reorient their preferences towards environmental spending. Using the pooled data from three General Social Surveys and employing an ordered probit (n = 1,113), this study examines whether political trust functions as a heuristic decision-making process and, as such, moderates the relationship between conservatives and attitudes to environmental spending. The findings demonstrate that conservatives have a negative attitude to environmental spending, but, when moderated by political trust, they exhibit a positive view.

By linking political trust to the relationship between ideology and policy attitudes and identifying the polarizing shift in views on environmental issues, this study makes a significant contribution to the literature on political trust and policy attitudes.

The study proceeds as follows: It starts with the evolution of the issue of the environment from a bipartisan to a polarized issue in the US. This is followed by a theoretical examination of political trust, ideology, and individuals’ policy attitudes. Next, the hypotheses are tested empirically, using the pooled data from the three GSSs and an ordered probit. Finally, the results are presented along with their implications.

The Environment as a Polarized Issue

The environment was once an issue that united both liberals and conservatives. Support for environmental legislation in the early 1970s stemmed from strong bipartisanship between Democrats and Republicans [3, 17, 18]. Political leaders rallied behind environmental spending and tried to ward off the pernicious effects of environmental degradation. Monumental bills such as The Clean Water Act and The Endangered Species Act were by-products of this consensual period. Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ (1962) inspired citizens and interest groups to do something about the environment [1, 2]. From today’s perspective, it seems ironic that it was conservative leaders such as Roosevelt who launched crucial conservational initiatives during the early 20th century, and Nixon, who created the EPA and introduced major environmental bills in the 1970s [19].

However, soon after the early 1970s, the political platforms of the Democrats and Republicans began to diverge sharply from each other [18]. This accelerated in the early 1990s and has widened to an extreme degree in recent years [18]. Conservatives and their interest groups began to see environmental issues as a threat to their political survival and tried to undermine environmental causes [20]. The Reagan administration made a series of attacks on environmental spending including an executive order mandating a cost-benefit analysis of government regulation and seeking the decentralization of government control over federal land [21]. Anne Gorsuch Burford, a rising anti-environmentalist with legal training and the mother of the future Supreme Court judge Neil Gorsuch, came to lead the EPA [19]. But enmity for the environmental agenda has ratcheted up a notch under the Trump administration [5].

The Trump administration has generated a bout of deregulatory measures to debase public support for environmental spending. In just over two years (from 2017 to 2018), the administration has set a formidable record and taken 78 deregulatory actions covering air pollution, drilling, infrastructure, animals, toxic materials, water pollution, and other environmental matters. As of December 31st, 2018, 47 rollbacks were complete, and another 31 measures were underway [5]. A few examples are sufficient to demonstrate the administration’s commitment to denuding environmental spending for the ostensive cause of boosting the market: lifting the freeze on new coal leases on public land, partially repealing an Obama-era rule on methane emissions, revoking the Obama administration’s flood standards for federal infrastructure projects, and dismantling a rule whereby coal mines were prohibited from dumping debris into local streams [5, 22]. In addition, coal plants are now allowed to operate without installing a clean-air device known as a ‘scrubber’ [23] and states have been delegated to decide on the amount of emissions they cut [24].

While some measures have run into prolonged litigation, the churning out of these rollbacks is said to pose a substantial public health threat to citizens [25]. The way environmental affairs are handled is exemplified in Pruitt, the person chosen to administer the EPA. He is a former Oklahoma Attorney General, who built his political reputation largely on defending oil interests and waging legal battles - 14 litigations to be accurate - against the Obama administration [26]. Under his tutelage, the EPA has turned itself into a protector of industrial interests to the detriment of environmental spending [27]. With Pruitt forced to resign amid corruption charges including renting a residence owned by a lobbyist and racking up personal travel and security expenses [28, 29], the EPA acts nothing like an environmental protection agency. In 2018, the agency’s environmental inspection rate fell by half compared with 2010, and civil penalties on polluters hit rock-bottom compared with those in 1994 [30]. Since the inception of the Trump administration, a significant number of veteran officials and scientists have left the agency involuntarily and staffing levels have been reduced to those in the Reagan era [31, 32].

Furthermore, the Trump administration has systematically undermined established scientific knowledge about climate change [10, 11]. Trump’s administration embodies the Republican’s stance on climate change calling it ‘fake science’ [12], despite the fact that the planet is becoming warmer. Many countries around the world have experienced unprecedented levels of flooding and wildfires [33, 34]. Normally reticent scientists have become alarmists and are voicing dire warnings about the threat of climate change to the planet [35]. A report sponsored by 13 federal agencies makes the grim forecast that unless the government takes measures to rein in global warming, the US economy will shrink by 10% by the end of this century [36].

In such an atmosphere, even farmers who have been affected by climate change talk about it without uttering the words, ‘climate change’ [37]. It is no wonder that the administration expressed no remorse when it pulled the country out of the Paris climate accord [38]. The evolution of the environment as a polarized issue points to the following hypothesis for empirical investigation:

Hypothesis 1: Conservatives are negatively associated with attitudes to environmental spending.

Political Trust, Ideology, and Environmental Spending

As previously noted, over the years environmental spending has begun to represent an ideological risk and a political liability to conservatives. In these circumstances, and in today’s politics, is there a mechanism by which conservatives can support environmental issues or at least support spending on it?

Scholars argue that political trust can serve as a mechanism for moderating one’s ideology regarding policy [13, 14, 15]. Defined as an ‘evaluative orientation’ towards how well the government functions based on citizens’ ‘normative expectations’ [39, p.791], political trust began to attract the attention of scholars in the wake of a series of events in the late 1960s and 1970s which also prompted a surge in public mistrust of the nation’s political institutions. Earlier studies focused on what influenced political trust [40, 41, 42], but soon shifted to the critical role of political trust in altering policy attitudes [14, 15, 16, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. Scholars note that political trust, reflecting concepts of performance and process, refers to citizens’ willingness to support government programs in a given policy area [15]. It also implies that individuals who mistrust the government are also less likely to support government programs.

Scholars note that when political trust is activated, individuals become more supportive of government programs even if such programs pose significant ideological risks. The impact of political trust is greater among individuals with an ideological stake in and with respect to a specific policy than those who would support it regardless [13, 14, 15, 16]. For example, Hetherington (2005) studied the relationship between political trust, ideology, and policy attitudes and found that political trust is activated when individuals are forced to sacrifice their ideological or material interests for others [13]. Political trust influences individuals’ attitudes to redistributive programs targeting black people but is not activated at all for distributive policy areas such as the environment and national defense [13]. Conversely, other studies examining the impact of political trust on the relationship between ideology and attitudes to conservative programs found that liberals become more supportive of tax cuts and social security privatization when moderated by political trust, as they are exposed to more ideological risks in relation to conservatives.

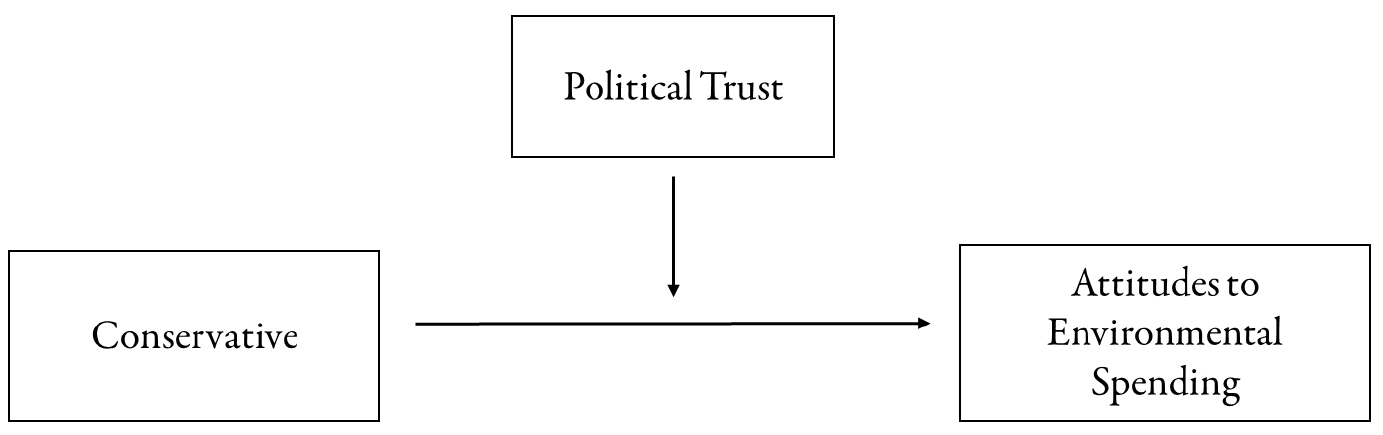

This study extends the scope of the existing literature by examining individuals’ attitudes to the environment and, specifically, to environmental spending. The environment has become a polarized issue imposing substantial ideological and material threats to conservatives. But the existing literature informs us that conservatives would be more supportive of environmental spending when moderated by political trust. Supporting environmental spending would not force liberals to make sacrifices because they would support it regardless of their trust in the government. Using political trust as a decision mechanism as in Rudolph and Popp’s study [15], this study examines whether ideology can be associated with environmental spending and whether political trust moderates the relationship between ideology and environmental spending. These rationales point to the following hypothesis for an empirical examination and Figure 1 visualizes the conceptual framework of the study:

Hypothesis 2: Conservatives become more supportive of environmental spending when moderated by political trust.

Measurement

Data

This study relies on data from the US General Social Survey (GSS) administered by the National Opinion Research Center [48]. The study employs the pooled data of the three GSSs (1996, 2012, and 2016) due to the small number of observations in each survey: 389 in 1996, 297 in 2012, and 427 in 2016. The three surveys were also chosen because they contained those variables most relevant to this study.

The GSS uses multi-stage stratified sampling and was administered every year between 1972 and 1994, and since then conducted every two years [48]. Only a core set of variables is available for every survey; and some variables reappear after several surveys. The respondents are not the same across the three surveys; consequently, the survey is cross-sectional in nature.

Variables

The dependent variable for the model is individual attitudes to environmental spending. Respondents were asked whether environmental spending was ‘too little,’ ‘about right,’ or ‘too much.’ The variable is reversely coded so that a value of one indicates ‘too much’ (preferring ‘less spending’) and a value of three indicates ‘too little’ (preferring ‘more spending’).

The major explanatory variables for the model are political trust and ideology. Political trust combines the two reverse-coded measures. Respondents were asked how confident they were about 1) the executive branch of the federal government and 2) Congress (correlation = 0.383). A higher value indicates more confidence in the nation’s political institutions and a lower value indicates less confidence.

Ideology measures the respondents’ self-assessment on a seven-point political view scale, which ranges from ‘extremely liberal’ to ’extremely conservative’. Three dummy variables (liberals, conservatives, and moderates) were created, with moderates serving as the reference variable. Scholars claim that ideology influences how one perceives environmental issues such as global warming, with liberals more conscious of environmental spending and conservatives showing less concern [49]. Using the measures of political trust and ideology, this study examines whether conservatives are negatively associated with attitudes to environmental spending and whether they become more supportive of environmental spending when moderated by political trust.

Finally, the model includes control variables to account for individuals’ spending preferences on the environment. The model accounts for political understanding. Studies show that people are more likely to exhibit pro-environmental attitudes when they possess a greater level of understanding of the political issues facing their country such as the potentially devastating effects of environmental deterioration and global warming [50]. Age is included in the model and expressed as levels ranging from one to five: one for ages 18 to 34, two for ages 35-54, three for ages 55-64, four for ages 65-75, and five for ages 79-89. The previous findings are rather mixed with respect to the relationship between age and individuals’ attitudes to the environment.

Scholars have identified a positive link between education and pro-environmental attitudes, where the educated tend to display a greater level of civic principles and environmental concerns [51]. Three dummy variables were created and two (less than high school education and college education or more) were included in the model with ‘high school education’ serving as the reference variable. In terms of individuals’ gender, women generally tend to exhibit a greater level of environmental friendliness than men [52]. Self-identification of class, touching on individuals’ perceptions of their personal wealth, was included in the model with three dummy variables (low class, middle class, and upper class) with ‘working class’ serving as the reference variable. Individuals who identified themselves as middle class or above are more likely to have the time and resources to cherish environmental values [53]. Regarding race, since whites are more likely to be more conservative than other races, they are more likely to express negative attitudes to environmental spending [54]. All variables except for political trust relied on a single item in the GSS. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables included in the model.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

Results

Since the dependent variable is a categorical variable ranging from one to three, the ordered probit model was used to test the impact of political trust on the relationship between ideology and attitudes to environmental spending [55]. Scholars note that turning ordered categories into binary ones results in the loss of crucial ‘information’ and ‘conceptual differences’ in several categories [56, p.650]. The model also relies on robust standard errors and includes a weight developed by the GSS.

Table 2 shows the results from the model. Step 1 denotes the direct relationship between the independent and dependent variables, whereas Step 2 is centered on the joint effects of ideology and political trust on attitudes to environmental spending. This study focuses on whether conservatives are hostile to it and whether their hostility shifts with the involvement of political trust. The results met earlier expectations. Conservatives maintained a negative relationship with environmental spending. However, when the conservatives were imbued with a higher level of political trust, they exhibited increased support for environmental spending. Conservatives are exposed to more ideological risks from environmental spending and consequently are subject to greater influence from political trust. As theorized, political trust did not moderate the relationship between liberals and environmental spending. Liberals are not exposed to the ideological risks presented by environmental spending; they would support environmental spending regardless of their confidence in political institutions. In terms of control variables, only age was significant and negatively associated with environmental spending.

Table 2.

Ideology, Political Trust, and Attitudes to Environmental Spending

| Coeff. | S.E. | Coeff. | S.E. | |

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||

| Liberal | 0.40 | 0.11*** | 0.49 | 0.39 |

| Conservative | -0.37 | 0.09*** | -1.27 | 0.31*** |

| Political Trust | 0.03 | 0.08 | -0.17 | 0.12 |

| Liberal x Political Trust | -0.04 | 0.22 | ||

| Conservative x Political Trust | 0.56 | 0.18*** | ||

| Political understanding | -0.06 | 0.04 | -0.06 | 0.04 |

| Age | -0.14 | 0.04*** | -0.13 | 0.04*** |

| Female | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.09** |

| White | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Less than high school | -0.02 | 0.14 | -0.03 | 0.15 |

| College education or more | -0.01 | 0.09 | -0.01 | 0.09 |

| Low class | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Middle class | -0.09 | 0.09 | -0.07 | 0.09 |

| Upper class | -0.25 | 0.19 | -0.29 | 0.19 |

| 2012 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| 2016 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| τ1 | -1.78 | 0.25 | -2.07 | 0.29 |

| τ2 | -0.67 | 0.24 | -0.95 | 0.29 |

| Log Likelihood | -937.98 | -929.81 | ||

| Wald Test | 98.48 | 110.55 | ||

| Number of Cases | 1,113 | 1,113 | ||

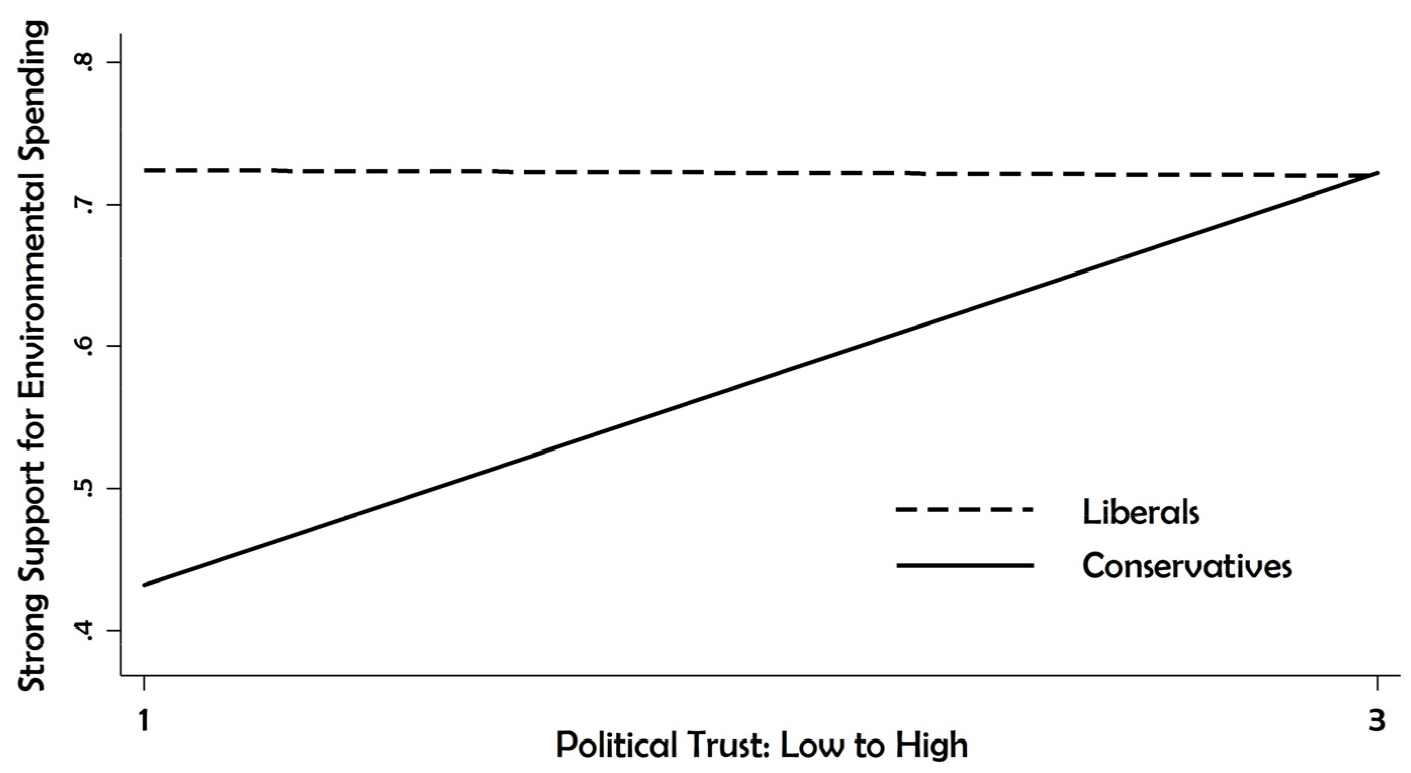

Table 3 illustrates the dynamic relationship between political trust, ideology, and environmental support, using the predicted probabilities of supporting environmental spending (‘too little’ of the dependent variable). Each variable is fixed at its minimum and maximum value while all the other variables are held at their mean value. The difference between the two can be interpreted as a one-unit shock. For conservatives, a one-unit shock from the lowest to the highest level of political trust substantially increased the support for environmental spending by approximately 29%. For liberals, political trust was a non-factor with little change in ‘strong support’ for environmental spending (-0.4%). The shift in the political trust level yielded little change for ‘strong support’ for environmental spending. Figure 2 illustrates the interactions between ideology and political trust in their joint effect on ‘strong support’ for environmental spending. As stated, as the levels of political trust shifted from low (political trust = 1) to high (political trust = 3), conservatives’ ‘strong support’ dramatically increased, whereas there was barely any change for liberals. Thus, these results affirm the study’s focus on the joint effect of ideology and political trust in their relationship to attitudes to environmental spending.

Discussion

The increase in environmental spending in the 1960s and early 1970s was fueled by bipartisan support in Washington, DC. A Republican president created the EPA, the agency responsible for environmental regulation. The consensual era, however, proved to be ephemeral. Soon after the 1970s, the environmental views of the two political parties veered sharply in different directions. Democrats have continued to maintain their enthusiasm for environmental causes, but their Republican counterparts have displayed hostility to it and even questioned the verity of climate change as a scientific fact. By the end of 2018, 47 attempts at deregulation were successful. The polarization of support for environmental issues has coincided with the devastating effects of climate change and their likely continuance in the future [33, 34, 35].

Is there a mechanism for predisposing citizens to be more friendly towards environmental spending in the contemporary political environment? Well, this study points to political trust as one of the heuristic devices that could help citizens overcome their ideological prejudices and support environmental spending. Some may doubt the usefulness of political trust in transforming policy attitudes. But an impressive array of studies has demonstrated that political trust is closely intertwined with policy attitudes and has practical ramifications. The topics studied include government demands [57], voting behavior [39], social welfare [13], tax cuts [14], and social security privatization [15]. This study examined the impact of political trust on the relationship between political trust and environmental spending (expressed as attitudinal support for environmental spending). Using the ordered probit model, it found that conservatives are more anti-environmentalist, but, when moderated by political trust, they showed more support for environmental spending.

The findings of this study provide some practical suggestions for contemporary politics and political leaders. American politics today is extreme in its partisanship and many are worried about the disappearance of the moderates [58, 59]. Others have observed that a centuries-old tool such as filibuster has been thrown out to advance partisan interests [60].

These ideological hostilities have been most clearly revealed in how political leaders treat environmental spending. The necessary involvement of the government in regulatory matters relating to the environment has presented an increasingly ideological risk to conservatives. Still, this study has demonstrated that even disagreements about the environment can be ameliorated if individuals have confidence in the political institutions. Knowing that political trust can be employed to advance policy agendas should motivate political leaders to make a concerted effort to nurture the public’s confidence in political institutions.

In recent decades, political trust has been seriously undermined, and the public have lost confidence in political institutions. At the same time, political leaders have made tactical decisions to attack the government for their own political gains. The Republican Party has risen to power by deploying an unrelenting barrage of claims about the federal government. From Nixon’s devolution to Reagan’s ‘starve the beast’ campaign and Trump’s ‘deregulatory state’, Republican leaders, even those residing in the White House, have assailed the government at every turn. In doing so, they have missed opportunities to rebuild the public’s trust in the nation’s political institutions and to push for their cherished policies.

Levels of political trust are no longer as high as they were before the 1970s. A cavalcade of political scandals such as Watergate, the Keating Five, and the Iran Contra outrage as well as America’s loss of economic might in global competitiveness has resulted in a historic low in levels of political trust. Others also point out that Americans do not display high levels of political trust because they are no longer primed to do so. The collapse of communism and the disappearance of identifiable foreign threats has led to a loss of a major issue that Americans can unite around and led them to exhibit abnormally high levels of political trust [47].

Still, small windows of opportunity have presented themselves during each administration in the form of national crises. For instance, the Bush administration used the September 11th attack as the launching point for its policy agendas such as the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) and the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA) when it enjoyed a high level of political trust from the public. Thus, for liberal causes such as environmental spending, liberal presidents are well-advised to find ways to cultivate and boost the public’s confidence in the nation’s political institutions. Suffice it to say, this is a formidable challenge. However, political leaders need to understand the immense potential in citizens who may increase their support for government programs even when they are to their ideological dislike, when moderated by political trust. This is a crucial lesson that today’s polarized political leaders should learn.

This study has examined the usefulness of political trust as a decision mechanism to reshape the policy attitudes of individuals. Nonetheless, the study has several limitations. First, as is typical in cross-sectional studies, the study is based on the data collected in the simultaneous timeframe. As a result, the threat of endogeneity between the dependent and explanatory variables exists, making it difficult to identify a causal relationship between the variables. Second, the study is based on a single source dataset. Because of the lack of multi-item measures, Harman’s single factor test could not be conducted, and a confirmatory factor analysis could not be carried out. Thus, the model may contain threats to the common method variance that can arise when a single dataset is employed. Thus, future studies, and preferably panel studies relying on multi-item measures, are needed to verify the causal relationship and identify how political trust may affect the relationship between ideology and policy attitudes.