Introduction

Perceived Climate Risk and Environmental Spending

Political Trust and Support for Environmental Spending

Measurement

Data

Variables

Results

Discussion

Introduction

A series of reports have noted an increasing number of severe weather events and worsening levels in terms of severity [1, 2, 3]. Severe storms and wildfires are threatening the livelihoods of many people, not to mention leading to fatalities [3]. A worsening degree of climate change is testing the concept of sustainability of the life we lead and questioning whether humans can continue to live a normal life without significantly altering their way of life [3]. Both governments and experts have raised concerns about climate change for a while, and have suggested immediate policy responses and strategies that will help reduce carbon emissions and mitigate the adverse effects of climate change [4]. However, implementing these require significant financial input from governments. In this context, it is critical to identify factors associated with citizens’ views with regard to environmental spending, which will ultimately promote environmental sustainability.

Among possible factors associated with individuals’ attitudes toward environmental spending, we focus on perceived climate risk. Borrowing an analogy from how perceived environmental threats can be defined, perceived climate risk can be defined as individual’s expectations of adverse effects by a given threat with respect to climate change [5]. We conjecture that perceived climate change can be positively associated with support for environmental spending based on the protective motivation theory [6, 7]. This theory posits that an individual’s expectations of a given environmental threat leads to that individual taking protective or ameliorative actions that help reduce such a threat [6, 7, 8]. Moreover, the more severe or vulnerable a given threat is perceived to be, the more such an individual becomes actively involved in reducing or alleviating such a threat [6, 7, 9, 10]. As perceived level of climate change becomes more severe, individuals may feel threatened and take action to deal with it. Thus, they may consider that such action requires substantial financial commitments, and supporting them in this way can be part of what constitutes protective actions. Naturally, it can be conjectured that an individual’s level of perceived climate change may be positively associated with his/her attitude toward environmental spending.

Political trust is another important independent variable in our study. We aim to investigate what role political trust plays in the relationship with regard to supporting environmental spending. We base our argument around the heuristic function of political trust [11, 12]. Scholars have noted that political trust functions as a heuristic for individuals with respect to deciding whether or not to support the government and its policies [11, 12, 13, 14]. Individuals rarely possess enough time, resources, and information to accurately assess what a given government policy is and what implications it has for citizens, making it difficult for them to decide what to do regarding it [11, 12]. Political trust provides them with an easy, psychological cue that enables them to judge a given policy [11, 12]. If individuals possess a high level of political trust, they are likely to see the merits of a given government policy and support it [11, 12]. On the other hand, if they do not have confidence in the government, political trust offers them an easy mechanism to distrust such a policy [11, 12]. Thus, political trust becomes a psychological judgement tool to allow the individual to quicky assess a government policy that he/she does not fully understand [11, 12, 13, 14]. As such, we argue that individuals will give the benefit of the doubt to government spending on the environment if they trust the government sufficiently. Thus, an individual’s level of political trust will be positively associated with his/her support for environmental spending.

More importantly, our study is centered on the role of political trust that might moderate the relationship between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending. Because of the heuristic function of political trust, it can magnify individuals’ positive attitudes toward the environment and government policies associated with it such as environmental spending, as well as alleviate individuals’ hostile attitudes toward such policies. As mentioned, we posit that individuals would be more likely to support environmental spending if they perceive climate risk at a high level. This positive relationship would be further strengthened if individuals are inclined positively toward a government policy if they place a greater level of trust in the government. Thus, we argue that political trust will moderate and help strengthen the relationship between individuals’ perceived climate risk and their support for environmental spending.

This study makes contributions to the understanding of dynamic relationships among perceived climate risk, political trust, and support for environmental spending. First, perceived climate risk matters in identifying how individuals view environmental spending. Relying on the 2021 Korean General Social Survey and an ordered logit regression (n = 693), the results confirm existing findings that perceived climate risk is closely related with support for environmental spending. Second, political trust matters in moderating the linkage between perceived climate risk and environmental behavior, such as attitudes toward environmental spending. In the present study, political trust did not have a direct association with support for environmental spending. Rather, its importance lies in interacting with perceived climate risk in understanding environmental behavior. It is possible that many other factors intervene in the linkage between perceived climate risk and environmental behavior; our contribution lies in pointing to political trust as one such mechanism. Third, our study adds a regional element to existing discussions of environmental support and spending by locating them in the context of South Korea where environmental support policies are being actively discussed.

Our study proceeds as follows. First, we examine the literature that links perceived climate risk and environmental spending. Second, we explore the literature of political trust and its association with environmental spending. Third, we examine the data and methodology used for our empirical model. Fourth, we subject the hypotheses to empirical testing. Finally, we discuss the results along with scholarly and practical implications.

Perceived Climate Risk and Environmental Spending

A worsening level of climate change is not just making global warming difficult to control, but also threatening human existence [4]. Deadly wildfires and storms have been devastating the environment and people living in it [4]. Environmental experts have long blamed climate change for extreme weather occurrences [3, 4]. Record-high temperatures and heavy rains are increasingly common across continents [4]. In the summer of 2023, South Korea endured an extended period of flooding, leading to over 40 deaths as a result of a lack of warning and unpreparedness with respect to the extreme natural disaster [15].

Given this context, it is important to investigate what factors may be closely associated with pro-environmental behaviors such as support for environmental spending. Among many possible factors, we focus on perceived climate risk (in terms of how much harmful effects climate change could have on South Korea). Perceived climate risk can be considered part of perceived environmental threats [5]. As such, borrowing from the definition of perceived environmental threats, perceived climate risk can be defined as the perceived likelihood of negative consequences that might be produced by climate change [5]. This study is based on the conjecture that perceived climate risk, as in the case of perceived environmental threats, would be positively associated with support for environmental spending. However, what mechanism might connect the positive linkage between perceived climate change and support for environmental spending? This study points to protective motivation theory with regard to establishing such a linkage [6, 7]. Protective motivation theory was developed in the attempt to understand the relationship between individuals’ perceptions of threats and their behavior decisions [6, 7, 16]. The theory is also based on the connections that link individuals’ expectations of threats and behaviors driven by their efforts to appraise such expectations [6, 7, 16]. The appraisal process, in turn, is composed of how much vulnerable the population appears to be and the severity of the outcome that a given threat may have [6, 7, 16]. Thus, when individuals expect that they are vulnerable to a given environmental threat and that this might pose a severe risk, they may exhibit behaviors that might allow them to cope with it [9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Based on these theoretical discussions, it is reasonable to posit that an individual’s degree of perceived climate risk may be positively associated with his/her support for environmental spending.

Several studies have shown that perceived environmental risk and pro-environmental behaviors such as support for environmental spending are positively associated [9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20]. When individuals sense a risk to their existence, they may exhibit a greater level of environmentally-friendly behaviors or of positive attitudes toward them [9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20]. For instance, there are positive associations between perceived environmental threats and environmentally-ameliorative actions [9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20]. The greater the environmental health threat, the more environmentally-active individuals become [9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Perceived environmental threats are positively associated with individuals choosing a lower standard of living and supporting a greater level of spending for environmental protection [21]. The discussions noted above can lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:perceived climate risk will be positively associated with support for environmental spending.

Political Trust and Support for Environmental Spending

We focus on examining the role of political trust in terms of its relationship with support for environmental spending. Political trust can be interpreted in terms of performance, integrity, and procedural fairness [11, 22, 23, 24]. If the government is conceived to be performing its duties well, individuals place a high-level trust in it [11]. Similarly, individuals would trust the government if procedures associated with government workings are deemed fair, and if the government operates free of political corruption and scandal [22, 23, 24]. Scholars have often pointed to political trust and its decline as negatively affecting citizens’ views with regard to a government and its policies [11, 12].

Because political trust consists of individuals’ perceptions of government performance, integrity, and procedural fairness, it functions as a psychological shortcut for individuals when they have to make a quick decision on government-related matters [11, 12]. Individuals are often confronted with various constraints such as lack of time, information, and resources, that limit their decision-making capabilities with respect to how the government operates, and how its policies would work in terms of its details and effects [11, 12]. Thus, they may feel ambivalent about whether or not they would lend their support to a given government policy [11, 12]. This is where political trust plays a part and enables individuals to make a quick decision regarding such policy [11, 12]. Individuals with a greater level of political trust can willingly support a particular policy, knowing that the trustworthy government would conscientiously perform its duties and devise and implement such a policy in such a way that would ultimately benefit citizens [11, 12]. Scholars have identified positive relationships between individuals’ level of political trust and their support of the government and its policies such as social welfare support, tax-cut, and taxation for environmental protection [11, 12, 13, 14].

Furthermore, we argue that political trust plays a moderating role in influencing the relationship between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending. As mentioned above, political trust functions as a decision-making tool for individuals with respect to government matters [11, 12]. As mentioned earlier, individuals’ perceived climate risk may be positively associated with their support for environmental spending. Political trust can strengthen the linkage between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending because it gives a positive signal to individuals that the government and its policies can be trusted [11, 12, 13, 14]. Thus, we argue that political trust can strengthen the positive linkage between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending. Based on the discussions above, the following hypotheses can be made for an empirical examination. Figure 1 exhibits the conceptual framework of this study.

Hypothesis 2:political trust will be positively associated with support for environmental spending.

Hypothesis 3:political trust will moderate the relationship between perceived climate change and support for environmental spending, such that the relationship gets stronger when the level of political trust increases.

Measurement

Data

For the empirical model, we relied on the 2021 Korean General Social Survey (KGSS) [25]. Following the U.S. General Social Survey, the KGSS consists of core items that are repeated every survey, and topical items that are repeated every few surveys. The KGSS relies on multistage area probability sampling that targets Koreans at age 18 or above [25]. The KGSS has been published since 2003, but we employed the 2021 KGSS because this survey contains all the variables needed for the empirical model [25]. The survey’s response rate was 50%. Finally, our empirical model is based on a sample of 693 individuals.

Variables

The dependent variable in our empirical model is support for environmental spending. It is based on one item. Respondents were asked to identify the degree of support with regard to environmental spending on a five-point scale; it was reverse-coded so that 1 indicates “spend much less” and 5 indicates “spend much more” [25]. As shown in Table 1, The mean of the dependent variable was 3.77, indicating that respondents on average were likely to be supportive of environmental spending.

The main independent variables in our model are perceived climate risk and political trust. First, perceived climate risk is based on one item. Respondents were asked to express their concerns about how much they perceived climate change would influence Korea; it was reverse-coded so that 0 indicates “a very good influence” and 10 indicates “a very bad influence” [25]. A higher value indicates a greater sense of risk for respondents with respect to climate change. The mean of perceived climate risk was 5.39, close to the actual mean of 11, indicating that respondents were split equally between “climate change is bad” and “climate change is good” [25]. As is suggested in the hypotheses, we expect that individuals with a greater level of perceived climate risk would be more concerned about the environment, and see the need for environmental spending more favorably, than those with a lower level of perceived climate risk.

The second main independent variable in our model is political trust. Political trust is a combined average of the two items: confidence in the executive branch of the national government, and confidence in the National Assembly (South Korea’s national legislative branch). Respondents were requested to indicate their confidence on a 3-point scale: 1 (hardly any confidence), 2 (only some confidence), and 3 (a great deal of confidence) [25]. The mean with regard to political trust was 1.55, indicating that respondents on average were less trusting of political institutions than trusting. In particular, the mean level of confidence in the executive branch was slightly greater than that with regard to the National Assembly, indicating that the respondents on average trust the executive branch more than they do the National Assembly. As hypothesized earlier, we expect that the more political trust individuals have, the more support individuals will exhibit towards increased levels of environmental spending because of political trust’s heuristic function. More importantly, we argue that political trust serves as the moderator that influences the relationship between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending, such that the relationship becomes stronger as the level of political trust increases.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

We also included in our model the variables that were thought to affect the dependent variables. First, environmental efficacy is included in the model. Environmental efficacy is a combined average of seven items. Respondents were asked to assess their strong agreement or disagreement with respect to the following items [25]:

1)“It is just too difficult for someone like me to do much about the environment”

2)“I do what is right for the environment, even when it costs more money or takes more time”

3)“There are more important things to do in life than protect the environment”

4)“There is no point in doing what I can for the environment unless other do the same”

5)“Many of the claims about environmental threats are exaggerated”

6)“I find it hard to know whether the way I live is helpful or harmful to the environment”

7)“Environmental problems have a direct effect on my everyday life”

The items were on a five-point scale; 1 indicates “agree strongly” and 5 indicates “disagree strongly” [25]. The second and seventh items were reverse-coded so that a high score indicates a stronger level of environmental efficacy, and a low score indicates a weaker level of environmental efficacy. The mean in terms of environmental efficacy was 3.08 with approximately half of the respondents feeling a stronger sense of environmental efficacy, and half of respondents feeling a weaker sense of it. Environmental efficacy is expected to be positively associated with support for environmental spending, as individuals who actively participate in environmental matters and decision-making are much more likely to see that the environment needs to be protected, and that such protection demands significant financial support from the government [21]. The rest of the control variables concern the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Age is expected to be positively correlated with support for environmental spending as older people are known to show greater appreciation for the environment ‘..and concern for its well-being than do younger individuals [26]. Female is an indicator variable. In terms of gender, women have been proven to be more compassionate about the environment than men [27]. Thus, they are expected to show more sympathy towards environmental spending. We also expect income to be positively associated with the dependent variable. As their income level increases, individuals would be more willing to support causes such as environmental protection and the governmental support needed for it [28]. Finally, individuals with a higher level of education are likely to be aware of urgent issues confronting the environment and the impact of climate change [29]. As such, they are more likely to support environmental spending than those with a lower level of education.

Results

For the analysis of our empirical model, we relied on an ordered logit regression as the dependent variable, support for environmental spending, which consists of ordered values that range from 1 to 5. For the analysis, we used Stata 14 software. Additionally, we accounted for the weight provided by the KGSS dataset and heteroskedasticity by employing the Huber-White sandwich estimator.

As shown in Table 2, our analysis proceeded in two steps. Model 1 explores direct relationships between the explanatory and dependent variables. Model 2, on the other hand, is centered on the moderating role of political trust by examining the interaction terms — perceived climate risk x political trust. The Wald test statistics for Model 1 and Model 2 are 60.76 and 65.53 respectively, indicating that the coefficients in the two models are significantly different from zero.

Table 2.

Ordered Logistic Regression Results

| Support for Environmental Spending | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | |

| Perceived climate risk | 0.21 | 0.04*** | -0.03 | 0.12 |

| Political trust | -0.00 | 0.18 | -0.69 | 0.35** |

| Perceived climate risk x Political trust | 0.15 | 0.08** | ||

| Environmental efficacy | 0.56 | 0.21*** | 0.56 | 0.21*** |

| Age | -0.00 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 |

| Female | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| Income level | -0.03 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 0.02 |

| Educational level | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Cut point 1 | -2.74 | 1.03 | -3.86 | 1.13 |

| Cut point 2 | -0.39 | 0.97 | -1.51 | 1.06 |

| Cut point 3 | 1.94 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.05 |

| Cut point 4 | 4.43 | 1.00 | 3.35 | 1.07 |

| Log likelihood | -804.15 | -801.60 | ||

| Wald | 60.76 | 65.53 | ||

The Model 1 results confirmed Hypothesis 1. As expected, perceived climate risk was positively associated with support for environmental spending. When individuals feel an acute sense of environmental threat with respect to climate change, they are likely to feel that some measures to alleviate such threats are needed, and to agree that the government should provide necessary funding for them [9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Thus, individuals with a greater level of perceived climate risk are more likely to support environmental spending than those with a lower level of perceived climate risk. Model 1, however, did not confirm Hypothesis 2; political trust was not significantly associated with the dependent variable. Political trust was expected to be positively associated with support for environmental spending, but, at least in our model, it was not in a direct relationship with the dependent variable to any significant extent.

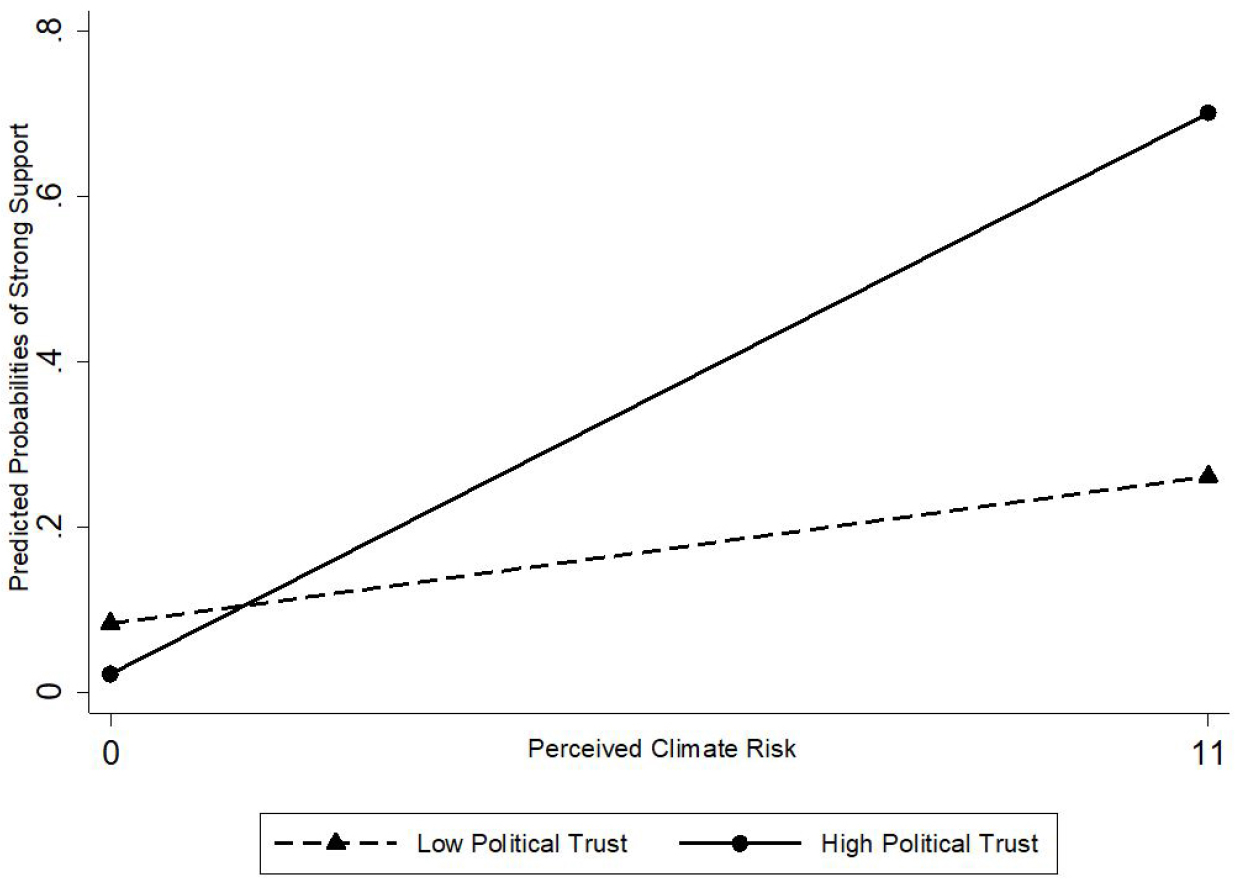

More importantly, we focused on whether political trust serves as a moderating role in the linkage between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending. The Model 2 results confirmed Hypothesis 3. This illustrates the potency of political trust as a heuristic device [11, 12]. Although political trust was not significant in terms of a direct relationship with support for environmental spending, the results demonstrated that political trust may function as a significant moderator with regard to the linkage between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending. As noted earlier, we argued that political trust can work as a heuristic for individuals when they must decide on whether or not to support a particular government policy [11, 12]. Individuals with a greater level of perceived climate risk are already inclined toward more environmental spending. Political trust works as an amplifier for the linkage. Individuals with a greater level of perceived climate risk would be more supportive of environmental spending if they possess a greater level of political trust. In other words, political trust exerts a powerful, positive impact on the linkage between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending.

In terms of control variables, environmental efficacy was the only variable that is significantly associated with support for environmental spending. Individuals with a greater level of environmental efficacy would be much more involved in environmental issues and decision-making [21]. As such, they are likely to be aware of important environmental issues that are becoming increasingly urgent as climate change rapidly reshapes the environment. Thus, they are more likely to support environmental causes and see the need for environmental spending than those with a lower level of environmental efficacy.

Figure 2 exhibits the visual presentation of the moderating effects that political trust has on the relationship between perceived climate risk and strong support for environmental spending, when the level of political trust is strong (a great deal of trust). The solid line denotes the relationship between perceived climate risk and strong support for environmental spending when the level of political trust is high. The dashed line, on the other hand, illustrates the linkage between perceived climate risk and strong support for environmental spending when the level of political trust is low. As shown, the slope of the solid line is much steeper than that of the dashed line. In other words, the level of strong support for environmental spending substantially increases when individuals possess a high level of perceived climate risk and political trust. On the other hand, the level of strong support for environmental spending does not increase much when individuals possess a high level of perceived climate risk with a low level of political trust. The figure clearly shows how political trust may exert a powerful force when interacting with perceived climate risk in supporting environmental spending, and warrants the inclusion of political trust in investigating the relationship between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending.

Discussion

The average temperature keeps falling, and the increasing severity of weather conditions is negatively affecting citizens around the world [3, 4]. As the trend in terms of climate change is unlikely to reverse itself, governments have begun to make efforts to adapt to, and mitigate, such environmental challenges by hosting international meetings and producing policy agreements [4]. However, the actual implementation of such measures demands government spending for which citizens’ taxation is mandatory and ensures the enhancement of environmental sustainability. Thus, this study explored what factors are associated with individuals’ attitudes toward environmental spending.

With regard to the current context, we explored two crucial issues. First, we examined whether perceived climate risk has any bearing on how individuals view environmental spending. Second, we explored whether or not political trust moderates the relationship between individuals’ perceived climate risk and their attitude towards environmental spending. Our findings demonstrate that individuals’ perceived climate risk matters in terms of their view with regard to environmental spending. Moreover, political trust plays a prominent role in moderating the relationship between perceived climate risk and individual support for environmental spending. The positive relationship between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending is further strengthened when the level of political trust increases.

The findings also revealed that political trust does not have a direct relationship with support for environmental spending. Because of its heuristic function, political trust was expected to be positively associated with support for environmental spending, but the results did not show that this was the case. At least in this dataset, the respondents did not demonstrate that an improved level of political trust leads to an increased level of support for environmental spending. This makes the moderating impact of political trust all the more important because such trust may not be a direct predictor of the outcome variable, but can still have a powerful impact as the moderator of the relationship between perceived climate change and support for environmental spending.

More importantly, the empirical model demonstrated the potency of political trust in moderating the relationship between perceived climate risk and support for environmental spending. However, it is one thing to argue for the importance of political trust, and another to suggest specific ways of improving it among citizens. For instance, according to a recent survey [30], the United States exhibits one of the worst levels of political trust. Even if that is the case, there are examples of countries in which political trust is not stagnant but is malleable, due to how the government responds to various circumstances and is seen to performs at its best [11, 12]. In South Korea, the Moon Jae-in administration enjoyed a predominantly high level of political trust when it was deemed to be doing a good job of handling coronavirus in its inception, from rolling out test kits to implementing contact tracing, setting up drive-in testing sites, isolating and supporting people with confirmed cases, and regulating the use of masks [31]. This resulted in a predominant political win for the government party (Democratic Party) during the parliamentary election in 2020 [31]. If a government is performing well, this leads to an increased level of political trust, whereas poor performance can result in the level of political trust plummeting. A series of government mishandlings in South Korea caused not just disappointment, but fury on the part of the citizens [15, 32]. In October 2022, the crowd crush incident in Seoul’s popular entertainment destination, Itaewon, resulted in 159 deaths including dozens of foreign nationals [32]. Lack of preparation, poor coordination among the various levels of government, and warnings against passing through an underpass in Cheongju during the flooding season in July 2023 led to the death of 14 people who were drowned when overwhelmed by overflowing water [15]. Each of these events have led citizens to doubt whether the government performs at all well, furthering the decline of political trust [15, 32].

Finally, our empirical model faces several limitations. First, it is based on a one-year cross-sectional dataset. Naturally, the findings cannot be generalized to different countries. Moreover, the data in the 2021 survey were collected in a similar timeframe. With no differentiations in data collection times, our findings cannot be considered causal. Furthermore, we did not implement Harman’s single factor and confirmatory factor analyses due to lack of multi-item measures. As such, the study may not be completely free of common method bias. Additionally, we examined only the relationships between political ideology, political trust, and taxation for environmental spending. Thus, scholars are advised to explore many aspects other than those we focused on but which may be related to individuals’ attitudes toward the environment and environmental taxation.