Introduction

Preliminary Study

Previous Efforts

Determination of Housing Program Alternatives

Research Methods

The AHP analysis

Development of Hierarchical Structure

Data Collection and Pair-wise Comparison

Evaluation Consistency Analysis

Synthesis of The Global and Local Weights

The PROMETHEE I/II analysis

Computing Processes

Partial Ranking PROMETHEE I

Complete Ranking PROMETHEE II

Result

Discussions

Conclusions

Introduction

Residents of Ulaanbaatar city have been suffering due to Ger Areas (GA) for the last two decades [1, 2]. As a result of the great, dramatic, and rapid rural-to-urban migration in Mongolia from 1999 to 2005 [3], about 45 percent of the total population of Mongolia is concentrated in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar (UB) [4]. Most of the migrants were low-income families from the countryside so they build and reside in Gers — round traditional nomad dwelling ‘yurt’, which originally functioned well for a nomadic lifestyle, but are poorly suited for urban living [5]. Moreover, these areas formed and expanded into populated sparsely, land surrounding UB without utilities or urban amenities because the government primarily granted free land ownership to the migrants without a master plan or municipal arrangement [6, 7, 8]. Therefore, during the last two decades GA have made the city one of the worst polluted cities in the world. GA housing situation is getting worse and resulting in many environmental, health, and socio-economic problems in UB such as various environmental pollution (i.e., air, soil, and water) [9, 10], disasters due to substandard Gers and detached houses decay (i.e., house fires, and floods) [11], diseases due to unsafe water-supply and heating, inadequate sanitation facilities, and environmental pollution (e.g., water-borne diseases which cause diarrhea, dysentery, and hepatitis A), and the problem is increasing annually [12, 13]. Approximately, 130 children and 1,250 adults died of pneumonia in 2019 which was an increase of 8,715 cases, compared to the previous year. Lastly, there is an absence of suitable roads. These are among the greatest challenges facing the capital [14]. For these reasons, GA need to be improved so that these major issues can be solved [1, 15, 16]. However according to the definition of informal settlement— “(i) areas where groups of housing units have been constructed on land that the occupants have no legal claim to, or occupy illegally; (ii) unplanned settlements and areas where housing is not in compliance with current planning and building regulations (unauthorized housing)” as published by The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), thus, GA have dual characteristics in that the GA residents have obtained the land ownership legally, but the living areas and housing conditions are in the form of informal settlements [2, 17]. Consequently, considering these GA characteristics, it has been difficult to develop and improve the situation of GA without sustainable housing programs [18, 19, 20].

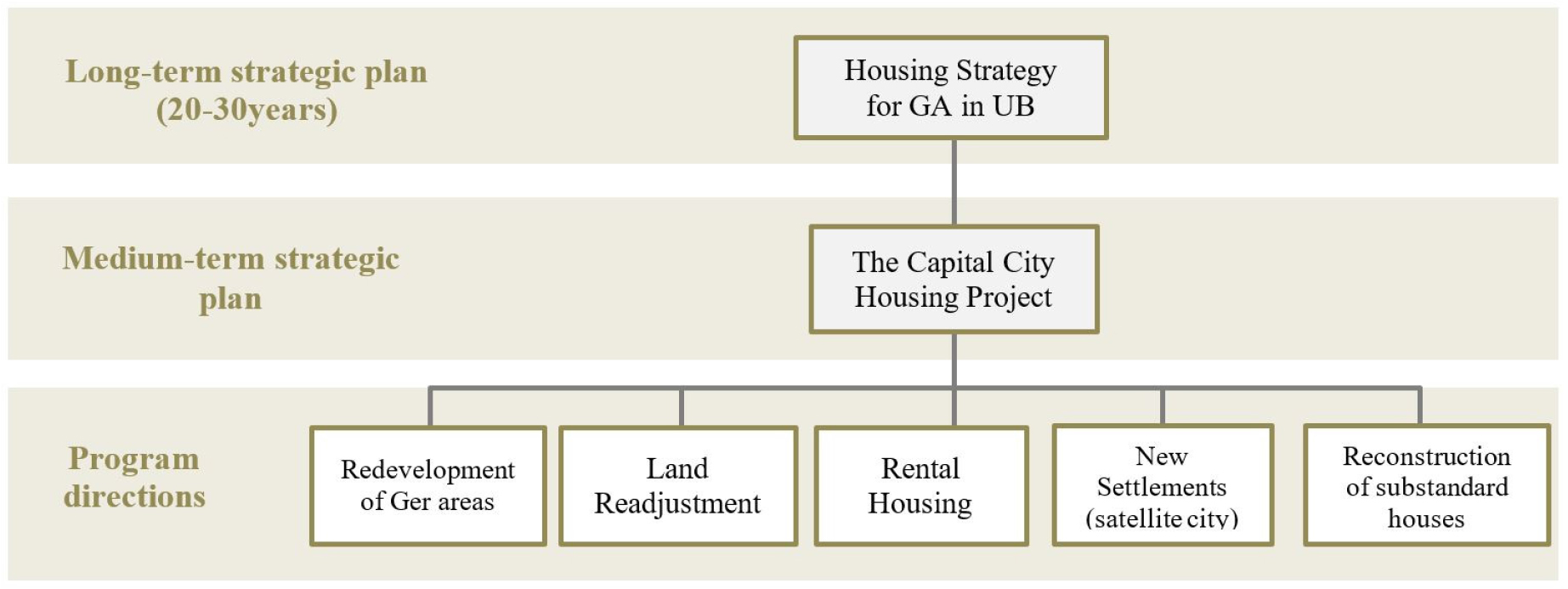

Since the early 2000s, the government has considered the housing issues of GA and implemented several housing programs which were mostly long-term policies with the goal of affordable and safe housing. Specifically, following a long-term master plan, the “UB Master plan for 2020” was officially implemented in 2002 [21]. However, this policy failed to achieve its goals because the planning and purposes were initiated imprecisely [15, 22]. Therefore, in 2013, this policy was revised and renamed “UB 2020 master plan and development approach for 2030”. It has five major implementing directions (see Figure 1) which are i) redevelopment of GA, ii) land readjustment, iii & iv) new public rental housing with settlements and a new city, and (v) reconstruction for old housing [23].

The directions included the following program goals by 2018. About 80,000 households of GA will obtain a house that connects with the central infrastructure through the redevelopment program. Around a hundred thousand GA households will be relocated to a new settlement such as a satellite town which will be built with a master plan, and rental apartments will be built for 3,000 households by 2020 and so forth [23]. Unfortunately, the total implementation of these programs reported barely 29.6 percent in 2020 [24]. There are two main reasons for the failed efforts of these programs. Firstly, five major program directions were unsustainable and ambiguous. For instance, the programs that resettlement of GA’s inhabitants and rental housings, there were two directions that were inconsistent with the intentions of GA’s residents [25, 26, 27], thus, the new settlement program had a major obstacle to achievement. Moreover, the residents preferred to obtain a property by bartering their own GA land for a house connected to infrastructure [28, 29]. Therefore, the rental housing program was not attractive to GA’s residents and provided rental house size too small compared to their existing dwelling in GA. In terms of directed land readjustment and reconstruction of old houses, the purpose of that program resembles the direction of the redevelopment of GA. So, it was not an exaggeration to believe that they would be included in the redevelopment of GA. Secondly, these five program directions were implemented without priority and consistency. In addition, the government has been administering these five program directions all at the same time leading to dilution of effort and less considering the sustainability. Therefore, the current housing policy continues to fail to reach goals and GA housing circumstances are getting worse.

There are sufficient studies related to the environmental circumstances of GA [30, 31] that have been already investigated by many local and foreign researchers and organizations through the past years. However, not much research or study has been done relative to the government housing program and policy sector. Especially, little attention has been paid to the sustainable housing program leading to better solutions to solve the issues of the current housing programs as mentioned above [19, 25, 32]. Accordingly, research on improving the current housing programs for improving GA is crucially important and urgent [3, 20, 25]. This research aims to propose sustainable housing program directions with priorities. With this in mind, the Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) was used to identify priorities for the implementation of programs.

MCDA statistical method has been increasingly applied to various types of program and policy evaluations because it offers the possibility of dealing with comprehensive and complex problems [33]. In addition, its advantage is incorporating criteria that demand synthesis. To identify these complex problems and criteria, suggested program directions were defined based on generic characteristics of housing programs to slum areas in developing countries. In summary, due to its appropriate multifaceted statistical method, the MCDA approach was selected as the research methodology of choice in this study. There exist various approaches to conducting MCDA research. In the midst of the approaches, principally, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluations (PROMETHEE) methods are commonly applied for selecting adequate programs in various fields [34, 35, 37]. For developing a hierarchical structure, major and sub evaluation criteria were identified based on literature survey (e.g. sides of government, developer, and GA residents). Measures were selected for three primary criteria, and also eight more criteria related to the three major criteria were identified as sub-criteria. In addition, there were six housing programs determined as alternatives based on other developing countries’ accomplishments and implementations to solve slum area housing issues. The AHP method is used for progressive pair-wise comparison, criteria weighting, and consistency evaluation analysis, while the PROMETHEE I method is used for partial ranking, and the PROMETHEE II method is used for full ranking estimation of the housing program alternatives. Then, from this analysis, the appropriate housing program direction may be suggested based on the results of the final ranking of the proposed alternatives.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 gives a brief specification of the literature survey. Section 3 presents the MCDA approach, the applied AHP, and PROMETHEE I/II integrated approach for selecting the programs and processes of the proposed methods and computing steps. Section 4 suggests sustainable housing programs based on the results with the final ranking of proposed program alternatives. Finally, section 5 concludes with major results drawn from this research and discusses further study.

Preliminary Study

Previous Efforts

Since the GA environmental situation has gotten seriously worse throughout the last decades, there is much research about GA and its issues. Most existing studies especially focus on GA environmental issues and propose studies, objectives, and trends that aim to experiment on the level of GA pollution and suggest effective approaches and measures to solve GA environmental issues. Whereas in terms of government intervention, the current housing program and its sustainability, effectiveness, and improvement were investigated less. In this sector, there is some research by international and non-governmental organizations. Before establishing the long-term housing policy, the World Bank [15] reported enhancing policy and programs with seven directions for GA development based on multi-sourced local reports. The directions are 1) access roads within GA, 2) better heating systems to improve efficiency and reduce air pollution, 3) solid waste management and community infrastructure, 4) research on affordable collective housing in mid-tier GA, 5) fringe GA, 6) utility capacity expansion and reforms, and 7) further research in related sectors. Generally, the directions focused on the environmental sector. Nevertheless, the point of these directions emphasizes the importance of further research and studies for the development of GA.

M.A.D investment [38] provided an overview of affordable housing and redevelopment of GA in UB because they anticipated that two directions are crucial for the development of GA. However, although the results were comprehensive and generous. [25] and [28] showed critical results about the current implementation of the GA redevelopment program which is included in the long-term housing policy. They concluded that the current redevelopment of GA is proceeding inadequately for GA residents. In addition, the program had several errors such as the systematic effort to produce greater profits for private developers, whereas GA residents suffer loss through direct and indirect ways. In addition, [39] focused on the adaptation of experience and program direction from experienced developing countries that faced similar problems. The researcher analyzed the South Korean case that solved slum housing problems. Although his research scope and results were comprehensive, the author less considered previous studies, efforts, and their results.

Determination of Housing Program Alternatives

The assessed housing program alternatives were chosen based on consideration of common features and housing program types of developing countries. Generally, developing countries have their own features and are different from each other. However, there are similar characteristics such as politics, social system, and the economy which tend to be similar [40]. For instance, the common feature in most developing countries has been to declare their independence after World War II, but before the war, most of them were colonies of developed capitalist countries. The economy and politics of these countries still tend to be under the influence of the former dictating countries while some of them became colonized again without being able to form and create their own political and economic systems [19, 41]. Moreover, developing countries’ poor economic development led to rural-urban migration due to market and living necessities especially in the capital city of the country. It was common in these countries that their governments lacked support for these migrants due to the scarcity of reserve funds and poor economic development. Most of the citizens moving from rural to urban had lower incomes. This led to an increase in slums in urban areas [30]. In other words, developing countries faced similar issues and were trying to solve the problems which some of them have solved through efficient policy and programs implemented by their governments. Therefore, in this study, assessed program directions were determined and collected within potential types of housing programs that might be acceptable to GA and the residents’ preferences. In addition, the program directions have been chosen because of their prevalence in housing issues in developing countries which have taken the challenge and overcome slum areas. The selected program options are as follows:

Self-help housing (SHH): This program usually has been implemented in countries whose economy is under-developed and unstable. Many developing countries adopting this program succeeded in solving their slum housing issues. For instance, there is “The Oranji pilot program” in Pakistan, ‘Kampung housing improvement program’ in Indonesia, and “land sharing program” in Thailand, and so forth. These kinds of programs share in the “do it yourself” principles included in SHH [42].

Multi self-help housing (MHH): It is no exaggerations to describe these kinds of programs as a modified type of SHH such as was used by the United States. The government provided reasonable and lower interest loans to residents with low incomes so they could make a resident building group, then, groups organize the building of houses by residents without government intervention [19, 42].

Public rental housing (PRH): There are several forms of this rental housing program depending on the implementing country’s features. In this kind of program type, the government builds houses and rents them cheaply to low-income residents who have housing problems. Many countries implemented this program such as Hong Kong, South Korea, and Singapore [43].

Social housing (SH): In general, the process of this program is a little bit similar to PRH. The difference is the resident can be own his house. In this case, the government provides affordable housing which the urban poor household rents and can eventually purchase [43, 44].

Joint redevelopment (JRD): this kind of type of program was accomplished in many countries such as in China, South Korea, and India. Private developers bear all costs required for this redevelopment project and supply the houses. The government mostly provides drainage system, infrastructure, and land. In some case, residents who have land, provide the land [42, 43].

New settlement or new satellite city (NS): This type is mostly implemented in high-density population cities and countries [44].

Research Methods

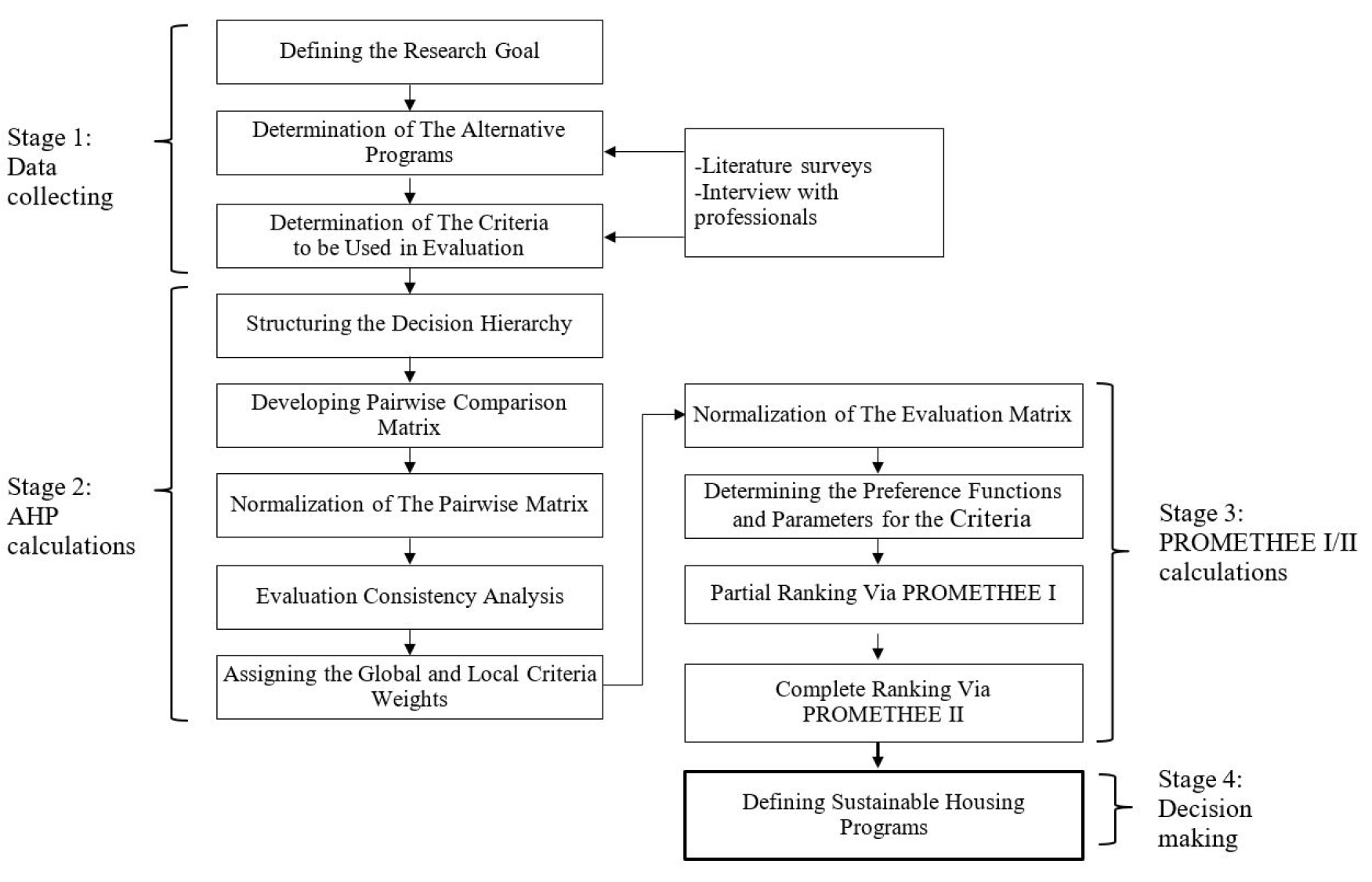

Selecting appropriate programs with multi attributes of admissible housing program options is especially important for the successful development of GA housing issues. Generally, the kind of selection is comprised of multi-criteria decision-making options. In this paper, the integrated MCDA approach is the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) which has been widely used by practitioners and researchers in addressing complex and complicated backgrounded decisions and represents a comprehensive perspective incorporating tangible as well as an intangible solution which is frequently unidentified by other evaluation methodologies [34]. The Preference Ranking Organizational Method for Enrichment Evaluations (PROMETHEE) approach was combined with the MCDA and is proposed as the sustainable housing program for GA housing. Moreover, it is crucially important to identify different preference functions of the criteria to make a correct decision [35]. Accordingly, integrated methods are used for decision-making that combines the AHP and the PROMETHEE. The AHP was used to analyze the structure of housing program selection, and to determine the weights of the criteria, and the PROMETHEE I/II method was used to obtain the final ranking and weight comparison of the program alternatives. Figure 2 represents a schematic representation of this research process.

The AHP analysis

The AHP method allows decision-makers: (i) to model a complex problem as a hierarchical structure that shows the relationship between the goal, primary criteria, sub-criteria, and alternatives, (ii) to integrate information and experience, and (iii) to measure relative magnitudes through a process of pair-wise comparisons [45, 46].

Development of Hierarchical Structure

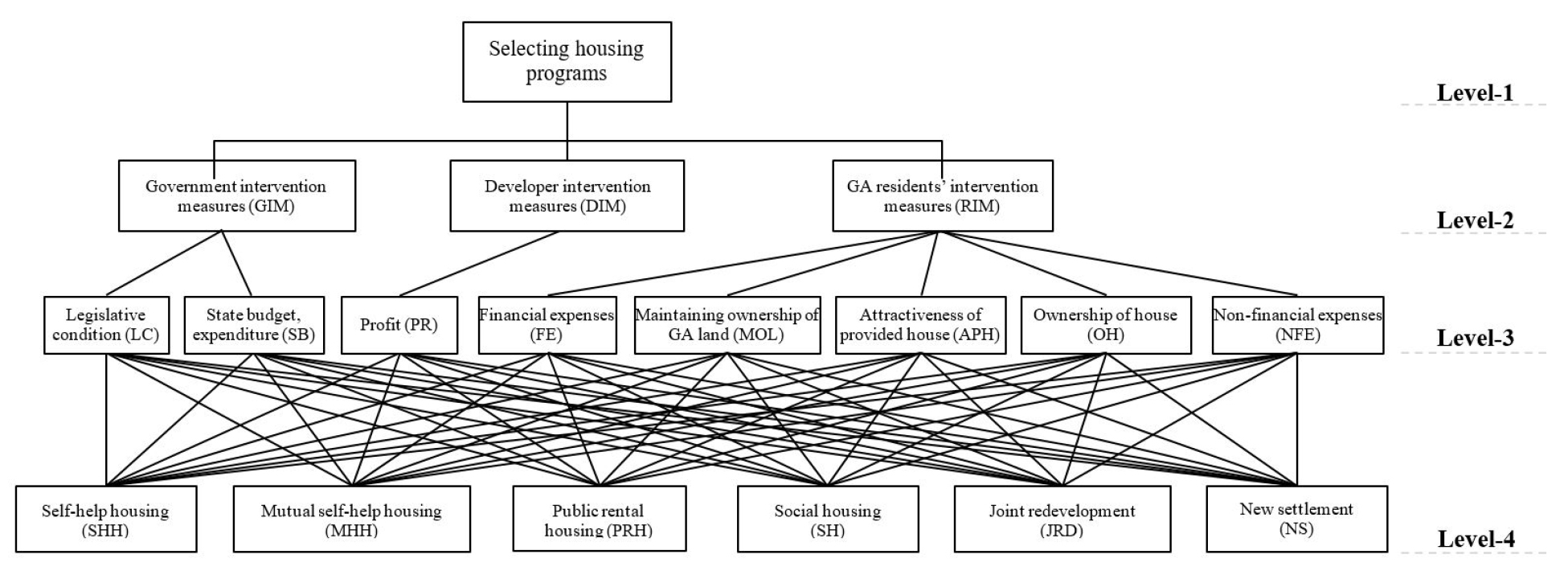

The foremost step in AHP is establishing the hierarchical structure that is consistent with the goal determined in level one [47], then selecting the appropriate housing programs for solving GA housing issues. Based on literature surveys and professionals’ suggestions in this field, the crucial criteria and the program alternatives were determined. Also, for identifying the criteria of the housing program the major stakeholders (e.g. government, developers, and GA residents) intervention is considered and the criteria are crucial for selecting the housing programs. Therefore, the primary criteria are determined to level two such as the Government Intervention Measures (GIM), the Developer Intervention Measures (DIM), and the GA Residents Intervention Measures (RIM). The sub-criteria, which correspond to the primary criteria are determined on level-3. Legislative Condition (LC) and State Budget expenditure (SB) are two of the sub-criteria in GIM, and profit (PR) is a sub-criterion of DIM. RIS has five corresponding sub-criterions; Financial Expenses (FE), Maintaining Ownership of the GA Land (MOL), Attractiveness of Provided House (APH), Ownership of the House (OH), and Non-Financial Expenses (NFE). The alternatives are determined on level four. Each alternative has its own value of criteria associated with it. Six potential housing program alternatives are identified to slum areas are considered. They are Self-Help Housing (SHH), Multi Self-Help Housing (MHH), and Public Rental Housing (PRH), and Social Housing (SH), Joint ReDevelopment (JRD), and New Settlement (NS). Figure 3 represents the hierarchy structure model.

Data Collection and Pair-wise Comparison

The next step is to create a pair-wise comparison matrix. This pair-wise matrix gives the relative importance of various attributes with respect to the goal. In order to collect pairwise comparison data to criteria consideration and for alternative housing programs based on criteria [33, 34, 48], six experts and professors in the field of GA’s development were asked pertinent questions. For pairwise comparison analysis, three main criteria and eight sub-criteria are identified based on the literature survey. Also, the question asked was from the interviewees: Question ‘A’: For sustainable housing programs for improving GA in UB, three main criteria and eight sub-criteria elements were identified: (i) government intervention measures with two sub-criterions, (ii) developer’s intervention measures with a sub-criterion, and (iii) GA residents’ intervention measures with five sub-criterions. Then the question ‘A’ is asked, “Which of these three criteria elements is of greater importance (priority) to you in the selection of the appropriate low-income housing program and how much?”

Based on their knowledge and experience, the interviewee gives an answer with a quantitative value to help create a pairwise comparison matrix amongst the given primary and sub-criteria. Once the priority matrix for the criteria is obtained, the next step in this stage is to evaluate each of the housing program alternatives with respect to the higher-level criteria. Question ‘B’: “Considering the primary criteria GIM, with regard to the contribution of the program concerned, which of the six housing programs offers a better potential to develop the GA and by how much?” Also, “Considering the criteria DIM, which of the housing programs has higher profits and by how much?”

A comparison scale is provided to the interviews for providing their responses. A 9-point scale was constructed as provided by Saaty [49]. The scale is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Saaty ‘nine-point intensity of importance scale’ for pairwise comparison

| Definition | Intensity of importance |

| Equally important | 1 |

| Moderately more important | 3 |

| Strongly more important | 5 |

| Very strongly more important | 7 |

| Extremely more important | 9 |

| Intermediate values | 2,4,6,8 |

Every input is rated on a 1-9 judgment scale to determine the relative importance of the different attributes on one level of the hierarchy related to one another. To compare ith criteria with jth criteria, the decision-maker assigns a value aij, which corresponds to a numerical value, an integer in the range of 1-9 as shown in Table 1. The length of the pairwise matrix is equivalent to the number of criteria used in the decision-making process. In this research, the pairwise comparison matrixes are set for each group of sub and primary criteria. The value in each pairwise matrix depended upon the results of the literature survey and interviews. The fractional value has been converted to a decimal value, and the sum of each value is calculated. In addition, the normalized pairwise matrix is calculated for estimating the criteria weights of the evaluation criteria (Table 3).

Evaluation Consistency Analysis

The quality of the output of the pairwise comparison is strictly dependent on the consistency of analysis results. The following equation defined the consistency index (CI) (Eq. (1)).

Consistency index:

where is the highest real eigenvalue; and n is the total number of factors.

Finally, the consistency ratio (CR) decides whether the evaluations are consistent, it is determined by dividing the CI with random index (RI) and is the CI of randomly generated pairwise matrix, as indicated in Eq. (2):

Consistency ratio:

where RI is the average random consistency index; and CI is the consistency index as mentioned above.

The value of CR is less than 0.1, which is the standard. As Table 2 shows, all of the values of CR assumed that the metrics are reasonably consistent. The measurement of the consistency is feasible to continue with the process of decision making using the AHP based on these criteria weights which can be used by the decision-maker for further computing. In level two, the criteria GIM has been given 0.52 weighted, the criteria DIM is 0.15 weight, and the criteria RIM weight is 0.33. About level three, there are two groups of the sub-criterions that are weighted. For instance, in a group of the sub-criteria in GIM, the criteria of legislative condition (LC) is a significant percent of 0.833, while another group of the sub-criteria in RIM is the criteria ownership of the house (OH) and has the greatest weight of 0.445.

Table 2.

Results of the consistency analysis of the evaluation criteria

Synthesis of The Global and Local Weights

There are sub-criteria involved in this decision-making. Each sub and primary criteria weight are computed individually, which is known as the local weights of criteria. The global weights of each criterion are associated with weights of criteria in level two, and local weights of sub-criteria in level three. The global weights (Table 3) are used for the final decision-making process as criteria weights.

Table 3.

Global and local criteria weights

The PROMETHEE I/II analysis

The preference ranking organization method for the enrichment evaluation (PROMETHEE) was developed initially by Brans in 1982, and further in 1985 improved by Brans and Vincke and in 1994 Brans and Mareschal [50, 51, 52]. This methodology is a manageable raking method in conception and application compared with other approaches used for multi-criteria decision analysis. The PROMETHEE I is partial ranking, the PROMETHEE II is the full ranking of the alternatives. Generally, the PROMETHEE approach and outranking methods have several advantages such as PROMETHEE I method achieves a synthesis indirectly and just requires evaluations to be performed of each alternative on each criterion [33].

Computing Processes

Firstly, the attributes are classified into beneficial or non-beneficial criteria. The criteria that are lower value are desired as non-beneficial criteria, better value is desired as beneficial criteria. Accordingly, the criteria SB, FE, and NFE are involved with non-beneficial criteria, whereas the remaining LC, PR, MOL, APH, and OH are defined as beneficial criteria. An evaluation matrix normalized using the following Eqs. (3) and (4):

For beneficial criteria:

Non-beneficial criteria:

where Rij is the ith normalized standard value; xij is the ith original value in jth criteria; max(xij) is the maximal original value; min(xij) is the minimal original value.

Secondly, the evaluative differences of ith alternative with respect to other alternatives are calculated. Therefore, consider a preference function P is determined based on the condition (Eqs. (5) and (6)). The preference function expresses the difference between the evaluations of two housing program alternatives (a, and b) in terms of particular criteria, into a preference degree ranging from 0 to 1 [53].

Preference function:

where Pj (a, b) preference function; Raj is normalized ath alternative under jth criteria; Rbj is normalized bth alternative value under jth criteria.

Thirdly, the aggregated preference function is calculated considering criteria weights using the following Eq. (7).

where is a global preference index of a over b; wj is criteria weight.

Therefore, a six-cross-six matrix is formed that is associated with the structure that has six alternatives. The aggregated preference function values of the alternatives are assigned and summarized in Table 4. For instance, the aggregated preference value of the program alternative SHH with respect to the alternative MHH is 0.022 and with respect to the PRH is 0.268, etc.

Table 4.

Aggregated preference function matrix

| SHH | MHH | PRH | SH | JRD | NS | |

| SHH | - | 0.022 | 0.268 | 0.128 | 0.114 | 0.187 |

| MHH | 0.231 | - | 0.362 | 0.221 | 0.106 | 0.287 |

| PRH | 0.206 | 0.090 | - | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.036 |

| SH | 0.206 | 0.090 | 0.147 | - | 0.015 | 0.066 |

| JRD | 0.342 | 0.125 | 0.312 | 0.165 | - | 0.224 |

| NS | 0.199 | 0.090 | 0.110 | 0.000 | 0.007 | - |

Partial Ranking PROMETHEE I

By using the aggregated preference function matrix above, leaving and entering outranking flows of PROMETHEE I/II are determined. The leaving (positive) flow and the entering (negative) flow for ath alternative is computed individually with PROMETHEE II and I. The leaving and the entering outranking flows of PROMETHEE I are calculated using Eq. (8) and Table 5 shows the results.

where leaving flow is the measure of the outranking character of the alternative; entering flow gives the outranked character of the alternative.

Accordingly, net outranking flow values utilized the crucial of the alternative characteristic comparison, according to the following equations (Eqs. (9), (10) and (11)).

Table 5.

Leaving and entering outranking flow (PROMETHEE I)

First, alternative a is preferred outranking alternative b,

Second, indifference situation,

Third, incomparable situation,

where P, I, and R are key preference indicators, respectively standing for preference, indifference and incomparability; a and b are the alternatives being compared.

Through the PROMETHEE-I in lieu of defining the rank preference calculated and the partial rankings are determined from the positive and the negative outranking flows [35]. The better the leaving flow the better value is the alternative. The lower the entering flow, the better value is the alternative. On the other hand, alternative a is better than alternative b if it is at least as good as all the other criteria. If alternative a is better on a criterion and alternative b is better on another criterion, it is impossible to decide which is the best alternative. Both alternatives are therefore incomparable. These are conditions that should be satisfied when the partial ranking process succeeds.

Complete Ranking PROMETHEE II

All the program alternatives are comparable when PROMETHEE II is considered [35]. The complete ranking provides direct and uncomplicated preference weights and preference functions. In addition, the leaving flow and the entering flow for ath alternative is computed using Eq. (12), in which for complete ranking outranking flows consider the average of the alternatives’ corresponding aggregated preference function.

where is the leaving flow; is the entering flow by PROMETHEE II; m is the number of alternatives.

The net outranking flow for each program alternative is demonstrated with Eq. (13), and the results are summarized in Table 6.

where is the net outranking flow for ath alternative.

Net outranking flow provides the complete ranking and sets the balance between the two outranking flows. The higher the net outranking flow, the better the alternatives.

Result

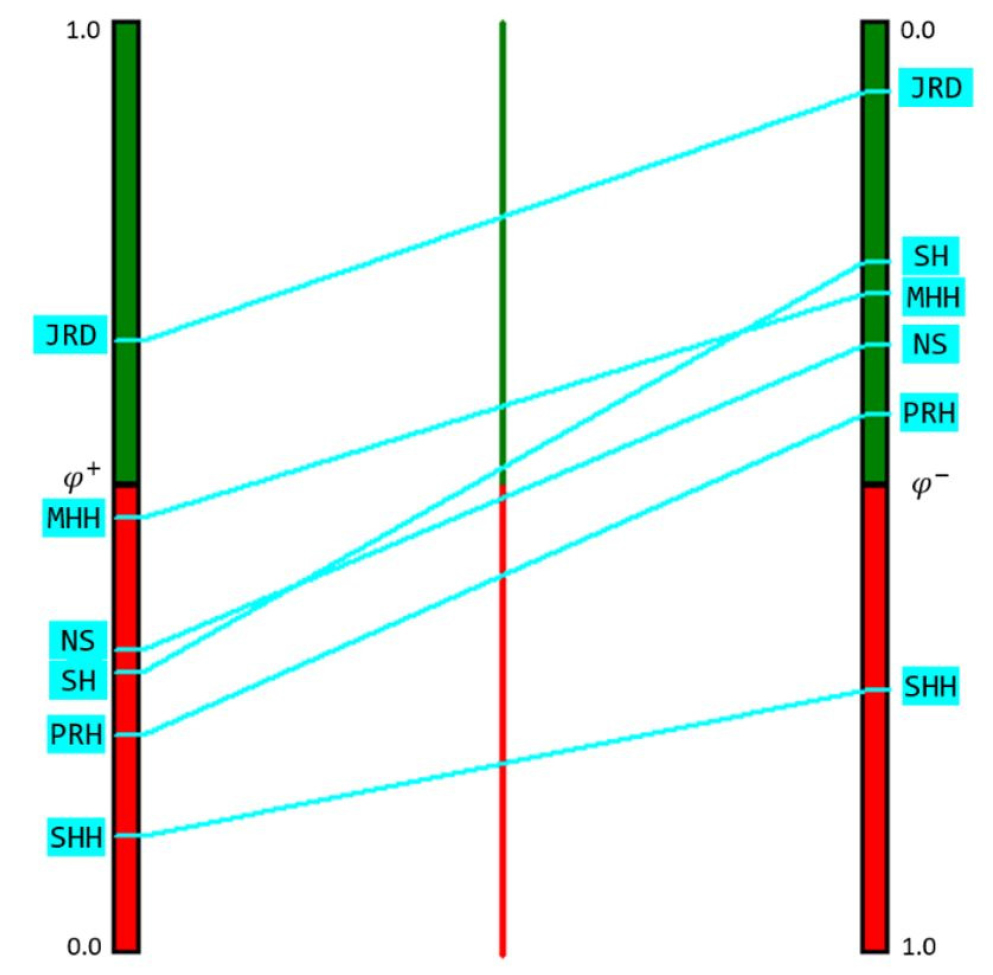

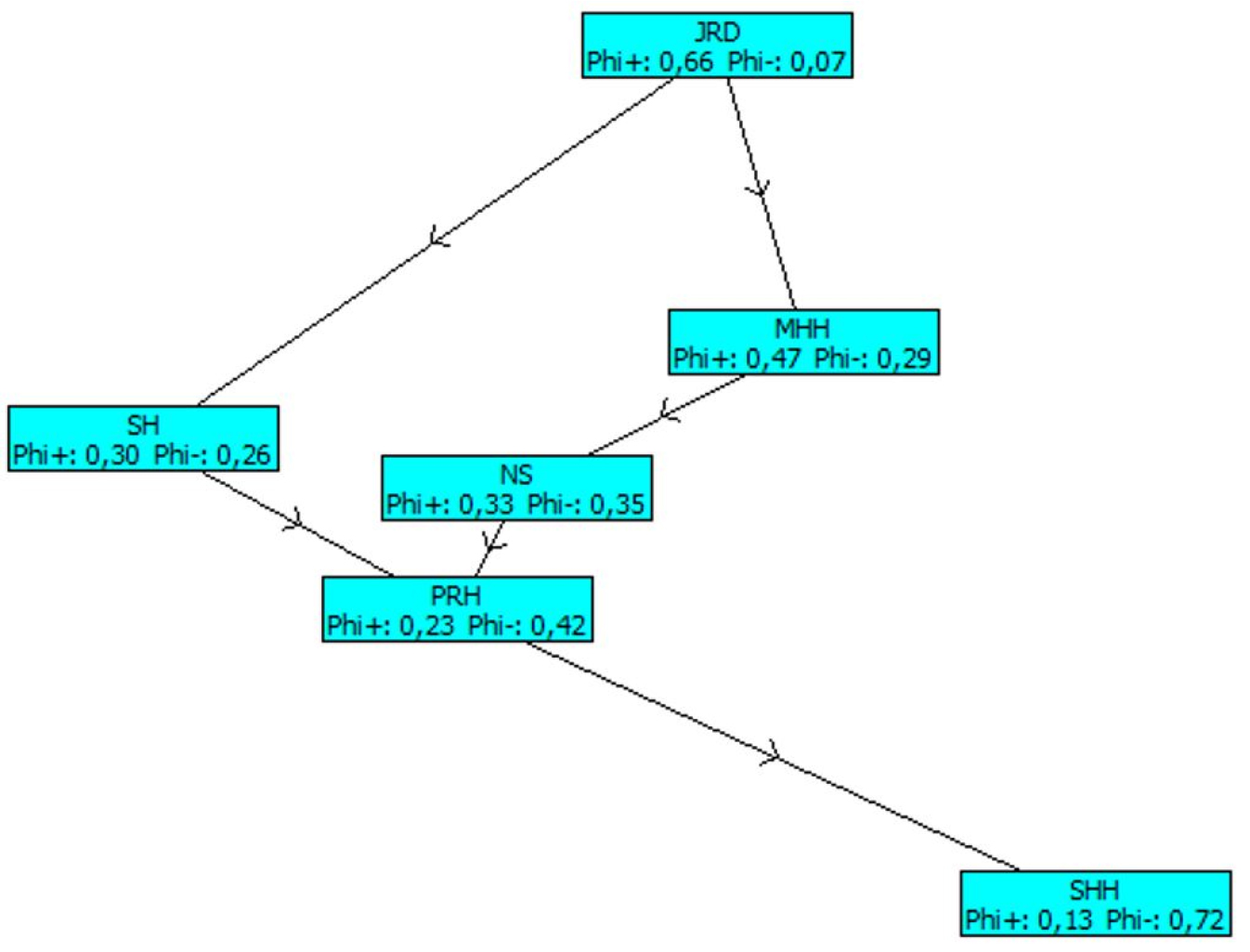

As mentioned earlier, currently there is a lack of research and studies related to the housing program sector for solving GA housing issues. According to [15] seven general directions are suggested for improving GA environmental situations. However, since that study, there are no other significant direction suggestions. Nevertheless, [25], and also [28] showed critical results about the current implementation of GA redevelopment programs, which is one direction for the long-term housing policy. In our study, six direction alternatives to housing programs were assessed, the alternatives were chosen based on a comprehensive literature survey in developing countries’ housing programs for the development of slum areas. The evaluating criteria and preference functions were defined by professionals in the field of GA’s investigation. In other words, interview questionnaires were provided by three experts and three professors who investigate GA housing issues and the intentions of GA’s residents. Suggested and selected program directions were evaluated for sustainability using the MCDA such as AHP and PROMETHEE I/II approaches with priority. Figure 4 represents the results of the overall preferred outranking based on key indicators via PROMETHEE I.

As can be seen, by using the entering and leaving flow values in Table 5, the partial ranking was determined (see Figure 4). JRD is preferred to all the other alternatives in PROMETHEE I ranking and SH is incomparable with the MHH and NS because it has a worse score on leaving flow () and a better one on entering flow (). The remaining program alternatives has comparable characteristics.

According to the synthesis of the preferred outranking (see Figure 5 and Table 6) via the PROMETHEE I and II, the program direction JRD is the considerable highest rank 0.59 whereas SHH was determined as the worst program alternative. Program direction MHH was preferred to SH, NS, PRH, and SHH directions. As is shown in Figure 5, the priority of ranked program alternatives was directed into two sustainable ways: firstly; program JRD is executed first, then MHH, NS, and PRH are in order. Secondly, SH and PRH should be executed after JRD.

However, SHH was determined inappropriate in the current situation of the GA because its value of leaving and entering flow was worst by PROMETHEE I (see Figure 4). Therefore, these results such as housing program priorities by the overall outrank and the comparable characteristics of the alternatives must support considerations by further program and decision-makers in this field.

Discussions

According to literature, there are a few previous studies reporting several housing program directions in the capital of Mongolia. However, these studies focused and considered environmental issues of GA or suggested program directions related to environmental pollution solutions, and not on the sustainability and implementation of government programs. Most of them concluded that GA’s in UB need improved, more appropriate, efficient, and sustainable housing systems. Moreover, the previous studies were written earlier, so there are few timely contributions that consider the current situation. In this study, we evaluated six housing program alternatives which were determined based on generic characteristics, and successfully implemented housing programs to slum areas in developing countries. We found that five of the program alternatives are available to solve the GA housing issues by using the MCDA approach with the AHP and PROMETHEE I/II methods. In addition, the improvement noted in this study was that the GA residents’ intentions were considered and reflected in the results based on interview questionnaires. Also, our results prove that among the five program directions for the current housing policy, redevelopment of GA, new settlement, and rental housing are three directions available for solving GA housing issues. However social housing (SH) and multi-self-housing (MHH) program directions are preferred over these three directions. Our results suggest two sustainable ways of alternative programs that are crucial to implementation. Most notably, after the release of failed results of the current housing program for GA that was mentioned in the introduction section, this is the first study that suggests reform of GA housing program implementation priorities. Finally, the overall preferred ranks and comparable characteristics of program alternatives are formulated. However, the limitations of this study encourage consideration only after careful evaluation of the current situations in UB and specifically the GA. Future work should focus on narrowed sectors and consideration of GA’s locational features. The housing program priorities are suggested as a basis that supports considerations for further programs and decision-makers in this field.

Conclusions

Since 2000, the Mongolian government has established and implemented several housing programs, especially long-term policy with a strategy for affordable housing focused on a solution to the GA housing issue. However, GA’s housing issues have been getting worse over the last two decades. Major problems are the implementation of the current housing program which has been inefficient due to unsustainable and incomplete comprehensive proposed directions which were executed without priority. Accordingly, this paper aims to formulate a decision approach providing for selecting appropriate and sustainable housing programs that are assumed feasible to solve and improve the GA housing issues. For this purpose, one of the powerful MCDA approaches that combine AHP and PROMETHEE I/II integrated methods is used for selecting the suggested program alternatives with priority for sustainability. For the MCDA process, evaluating criteria and preference functions were defined by six professionals who are in the field of GA’s investigation for developing the hierarchical structure. The program alternatives were determined based on the literature survey with respect to the availability of a solution in the slum areas in developing countries. Based on the hierarchical structure, a pairwise decision matrix used in the AHP process, introduced the preference of the decision-makers in which all the criteria were compared, and local and global criteria weights were computed. The PROMETHEE enriches AHP by associating a preference function to each evaluation criteria. Therefore, for analyzing the decision-making problems, PROMETHEE-I determined partial ranking and PROMETHEE-II provided the complete ranking of the proposed housing program alternative priorities.

The PROMETHEE I/II results showed JRD is preferred over all the housing program alternatives and after JRD that MHH, SH, NS, and PRH are ranked. Whereas according to the partial ranking assessment, SHH is the worst alternative, thus, according to the results, this program direction is inappropriate for the current GA’s situation as a solution. Moreover, two sustainable housing program implementation directions for improving the current situation of GA were suggested based on a synthesis of preferred outranking by the PROMETHEE application.

This study is important for several reasons. First, the suggested program alternatives were chosen with consideration of successful housing programs to slum areas in other developing countries. Second, contrary to the current housing programs, this study provides sustainable program directions with execution priorities. However, our results encouraged and should be considered in the current socio-economic situation of GA in UB. Future work should focus on narrowed sector and housing strategies, and program directions with consideration of GA’s local characteristics. In addition, the results of this study may provide sensitive information for developing and improving the current GA housing programs and for decision-makers.