Introduction

This research explores the nature of outdoor and transitional spaces in schools in terms of their architectural characteristics and pedagogical needs which can also provide environmental benefit such as thermal comfort and energy reduction [1, 2]. Outdoor spaces are an important part of the school environment, providing students with open spaces in which to run around meet others and enjoy the natural world. There are no building regulations for outdoor classrooms but recommendations of their necessity and design tips can be found in the publications by DfES which give pedagogical reasons for having such spaces and suggest how the space might be manipulated [3, 4]. However, indoor classroom design is subject to building regulations, which can be influenced by the exposed or partial shelters in various forms and ratio of open spaces [5]. For example, solar radiation may be blocked partly or wholly by an attached outdoor space, thus instantly having an effect on the daylighting levels in the classroom which the regulations state must provide a minimum 300 lux at desk height [6]. Also, the transitional space may affect the solar gains in the indoor classroom, leading to a breach of regulations regarding overheating, which state that the classroom should have fewer than 80 hours of temperatures above 28℃ whilst occupied throughout the academic year [7].

In the past few years, there has been a significant increase in the opportunity to improve school environments in the UK due to an increased capital investment in school buildings. Sustainable schools could be expected to provide healthier and more productive environments because the factors that contribute to a sustainable building (daylight, fresh air, materials with low pollutants, etc.) correlate strongly with factors known to contribute to health and wellbeing [8, 9]. With large numbers of students in education and a major investment in school buildings, the benefits to teaching and learning through environmental measures are immense.

The nature of the interdisciplinary research presented here requires an understanding of the wider context of the subject. It is therefore necessary to review school designs of both earlier and current periods, particularly in relation to outdoor space patterns; this provides help in understanding the roles played by outdoor spaces in schools and how such spaces relate to classrooms environmentally and educationally. A review of historical cases and typologies of schools provides an understanding of how similar challenges have been approached in the past, and this can serve as a basis for creative directions even if the solutions reached then may need adaptation for the current building design.

Outdoor space in a school

Outdoor spaces are one of the typical school features that are different in function to the rest of the building, catering for physical education, which is an essential part of the school programme. Many things take place in the outdoor spaces in schools, including running, chasing, chatting, sports and outdoor observation. The primary school curriculum, in particular, includes the playing of many personalised games and these are often based on imaginative responses to their environment [10, 11].

A school’s outdoor spaces are potential educational places. In addition, they can present a positive image to the community. For example, green spaces can act as welcoming surroundings having a positive effect on the experience of both the students and other regular users of the school premises. The design of outdoor spaces is aimed at providing a stimulating, safe and secure environment in which students can play and learn with enjoyment. Outdoor spaces in school can largely be divided into three main areas: the area adjacent to the buildings, the playground, and the pitch and parking areas. Adjacent areas are normally the immediate boundary areas of the school buildings; these are often green areas for planting or where benches are provided as resting places. This area can also be used as a circulation area or as extended classrooms if enclosed by fences or trees. The playground is the place where play equipment is installed outside the buildings: pupils can run around within the playground areas. Pitch or car parks are normally located at greater distance from the school buildings and form a school boundary between the school and the surrounding community.

Pedagogical Functions

School grounds can provide a wealth of interest and resources for both personal and social education. The National Curriculum can be supported to an extent by studies outdoors, and a number of these are cross-curricular. Such direct experience in observation, investigation and participation in design and development of grounds helps pupils to be informed, responsible and enterprising [12]. Guidelines for environmental design in schools recommend that external spaces should be an integral part of a school’s design. Proper planning and landscaping of these spaces is important not just for aesthetic reasons but also because of the requirements of parts of the curriculum. In particular, for the under fives, physical experience is a valuable component of learning [9]. Education Outside the Classroom (from a report of Education and Skills Committee in 2005) concluded that “school grounds are a vital resource for learning” and that “capital projects should devote as much attention to the ‘outdoor classroom’ as to the innovative design of buildings and indoor space”. When imaginatively developed, school grounds can contribute to curriculum teaching and learning, and to better recreational and social interaction of their pupils. In addition to contributing strongly to children’s understanding of ‘green’ issues, they can make a positive impact on the sustainability of the schools and their locality.

Providing sheltered spaces in outdoor would be helpful for pupils to use the space throughout the year regardless of weather conditions. Even though there are no specific guidelines for the outdoor spaces and duration period need to stay outdoors, sheltered spaces e.g., canopy is frequently used in order to enable its use for as much of the year as possible. Easy access to the outdoors from the classroom enables teachers to use the outside as often as possible [4]. For the early years sector, free flow between inside and out is essential. But even for older pupils, direct access to the outside from their classrooms means that more frequent use of the outdoors is more likely. Outdoor work, like that inside the classroom, can incorporate various subjects (e.g. painting, maths, science, etc.) whilst providing opportunities for enjoying nature. The outdoor classroom published by the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) in 1999 highlighted the potential of school grounds as a valuable resource that can support and enrich the whole curriculum and the education of all pupils [3]. The research has also indicated that the scale and typology of spaces inside and outside should relate more closely to the needs of the developing child, and that more variety should be provided in the outdoor environment. This might include sheltered bays (paved or soft areas) where small groups of children can gather to occupy themselves quietly in a pursuit which may be self-chosen or part of a curriculum-based activity. Larger sheltered spaces can enable groups of class size to work together. Extensive open spaces can provide for field games and other events, which may be anything from a celebration of a seasonal festival to a hot air balloon launching.

Methodology

One of the most important recent projects for UK school buildings initiated by the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) is the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme. As a part of the scheme, eleven leading architectural offices were commissioned in 2003 to design exemplar schools; five for primary schools, five for secondary schools and one all-through school, all to the equivalent of the RIBA Plan of Work Stage C, Outline Design. The designs are intended to develop a shared vision of ‘schools of the future’ and create benchmarks for well-designed schools [9]. It will therefore be beneficial to provide an investigation of the schemes associated with the exemplar schools in connection with the provision and typologies of outdoor space.

Most school building schemes listed in architectural publications by DfES show in particular the interdisciplinary nature of outdoor learning and provide advice on the educational design and management of external spaces. The Outdoor Classroom provides useful examples of how school grounds may be used effectively to teach language, mathematics, science, geography, drama, art, music, and more. Outdoor learning spaces can include an atrium, a courtyard, a covered yard or veranda, pathways, play structures and seating areas, which all offer direct benefits for outdoor learning. Depending on the age groups, it can also be useful to consider the types of play in which children engage and then design areas to accommodate these play types [3, 13].

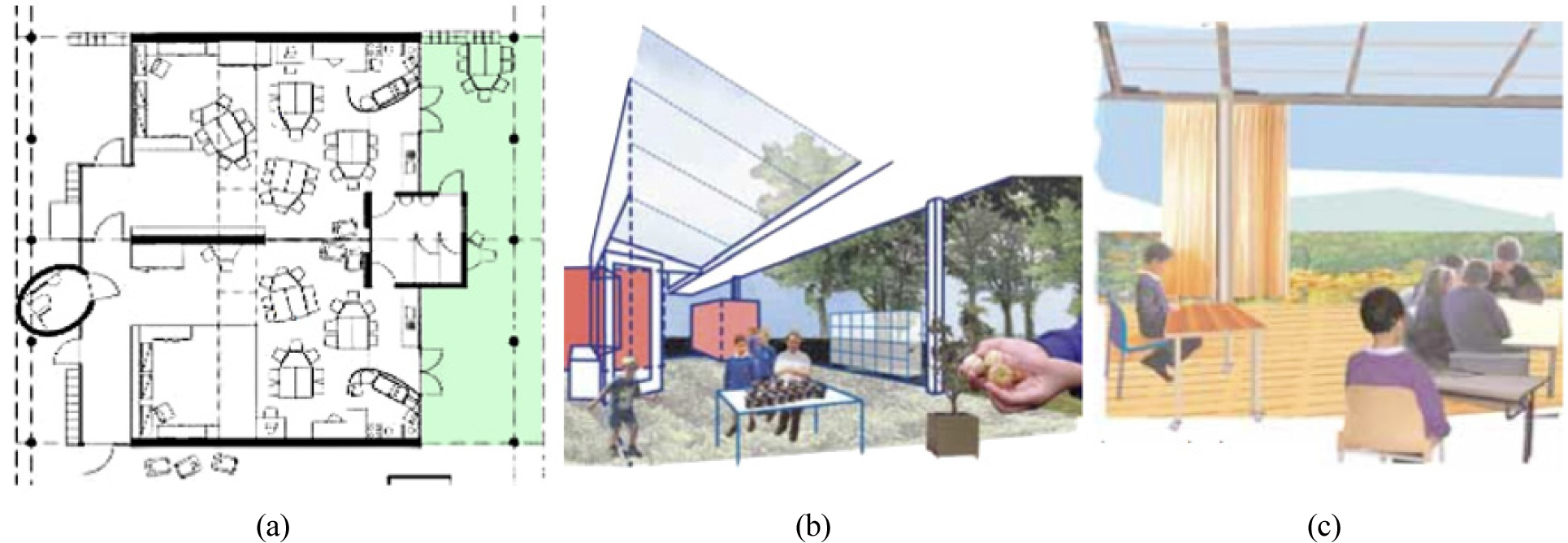

The architects Cottrell and Vermeulen suggest the use of a canopy for an external classroom and class-base shared spaces. There are different ways in which a canopy can be arranged to suit the particular site strategy: for example, two or more canopies can be arranged to produce a large continuous canopy or one with wings and courtyards. The overlap of two or more of the canopies can create a central shared zone which links the entrance and community block to the classrooms and landscape and which houses shared resources and dedicated subject-teaching areas. The schematic plan of Figure 1 shows how seasonal use of the transitional space can be envisaged by using toilet doors as a seasonal passageway which minimises the inlet of cold air in winter.

This kind of flexible use of the entrance to the outdoor spaces would be very helpful in promoting the frequent use of the outdoor spaces during the school. The architects Walters and Cohen also noted that external teaching has long been recognised as a key part of the education of children in Figure 2. In this design each pair of classrooms opens out onto an outside classroom. Different outdoor furniture is used for different age groups. Tables and chairs suitable for older children provide an outdoor space where curriculum-led lessons can take place whilst sandpits are more appropriate for the lower year groups. Each classroom has a corresponding outdoor teaching garden. Shelter is provided by a transparent canopy that modifies the microclimate to help promote growth of more exotic plants. The nursery garden has a small lawn surrounded by a mixed-species ecological hedge to create a sense of privacy and provide protection from the wind. As with the scheme by Cottrell and Vermeulen, the toilet can also be utilised in the improvement of energy demand through providing seasonal passageways as shown in Figure 2(a). Access to the outdoor classroom can be provided via the toilet, which can help reduce the heat loss from the door to the outdoor spaces by frequent use of by students. A simple wooden pergola and trellis provides a structure on which to grow plants as shown in Figure 2(b). This planting will shade the space in the summer months when the leaves are out, and will allow the warm sun in during the winter months when the foliage has died back. A polycarbonate roof protects children from rain while they wait to enter the classroom and also permits external dining and teaching.

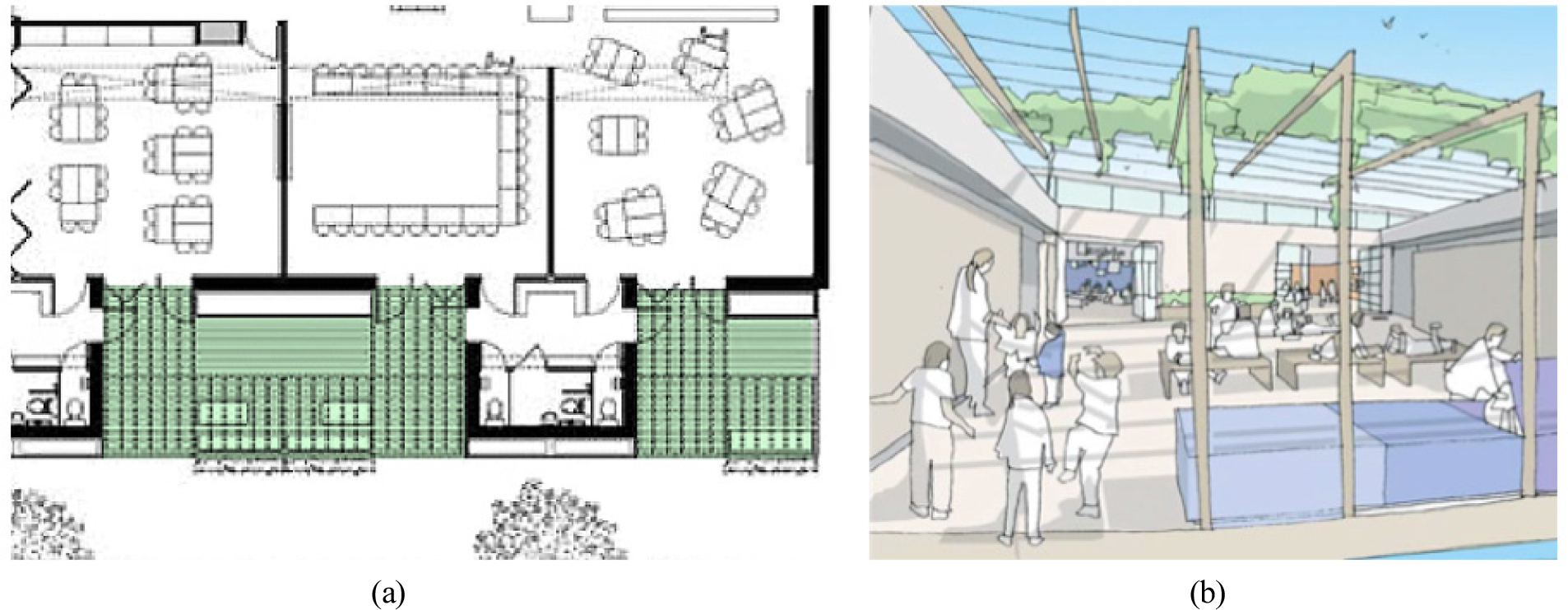

A similar outdoor classroom can be found in the scheme of Marks Barfield. An outdoor teaching space is provided for each classroom, with a separate play/ teaching area for Early Years and Reception. These recessed spaces generally have a hard surface, which could consist of paving, tarmac or even timber. Timber can be cantilevered out to create level surfaces on sloping sites as can be seen in Figure 3. The classrooms are organised around a central open space that is envisaged as a meadow. This is accessed via a pergola which doubles as a semi external circulation corridor. The proposals respond to the Learning Through Landscapes model and outdoor thermal comfort [14]. Outdoor spaces close to the school buildings, such as the meadow, are designed to encourage outdoor teaching for almost any subject [9]. The half-surround playground has a child friendly synthetic surface and like the outdoor classrooms in the central space has integral verandas on the east side of the building so that there is always an alternative covered space in which to play when it rains. The edge of the playground is gently mounded and edged with low planting before dropping away to the trench boundary. The covered outdoor teaching spaces can allow pupils to enter the playground and arrive at each classroom while waiting for the classroom to open.

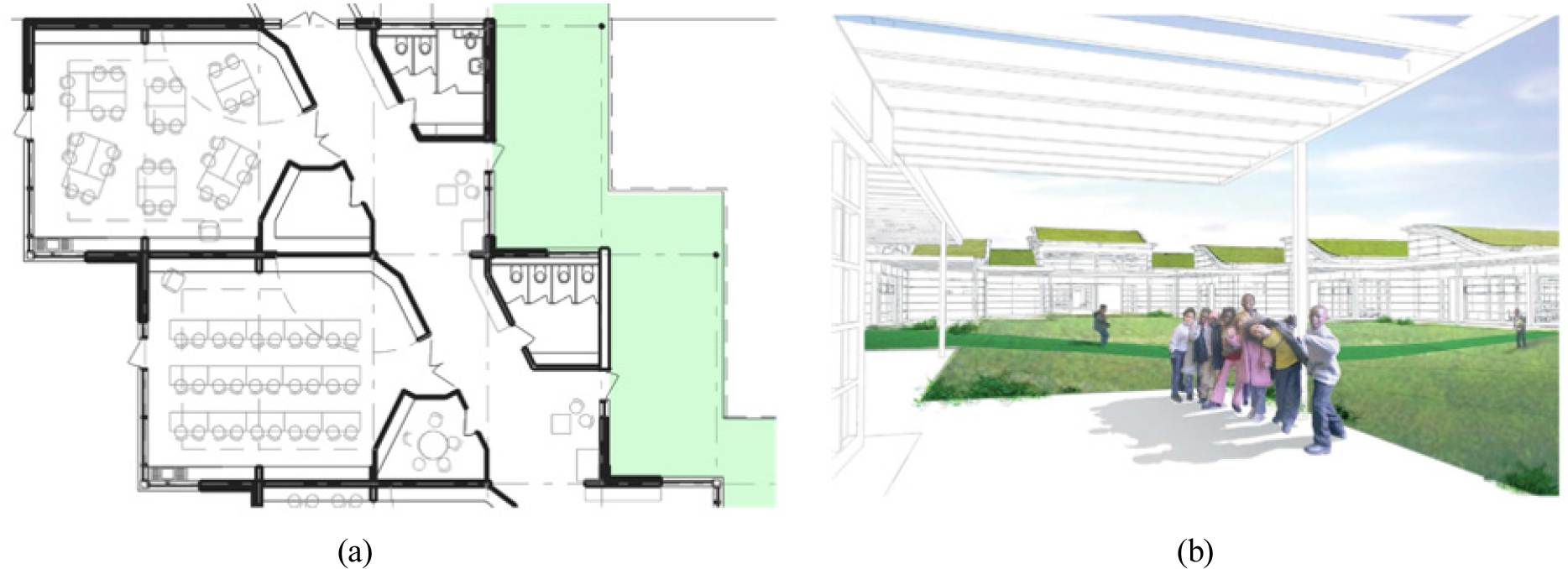

The proposal by Wilkinson Eyre architects has identified two types of building; learning clusters or ‘villages’ and central facilities as seen in Figure 4. A covered canopy links these school buildings, forming an environmentally protected outdoor space in the middle of the school, used for circulation and external teaching spaces. The “kit-of-parts” approach here lends itself easily to providing solutions for different sites, and could be expanded incrementally as a school grows or added in phases to an existing school.

Through these examples of the transitional space in the exemplar schools in the UK, there are growing interesting examples of semi-outdoor spaces from primary to secondary school. Analysis of the various examples will provide ideas of typology for the outdoor spaces in schools

Analysis

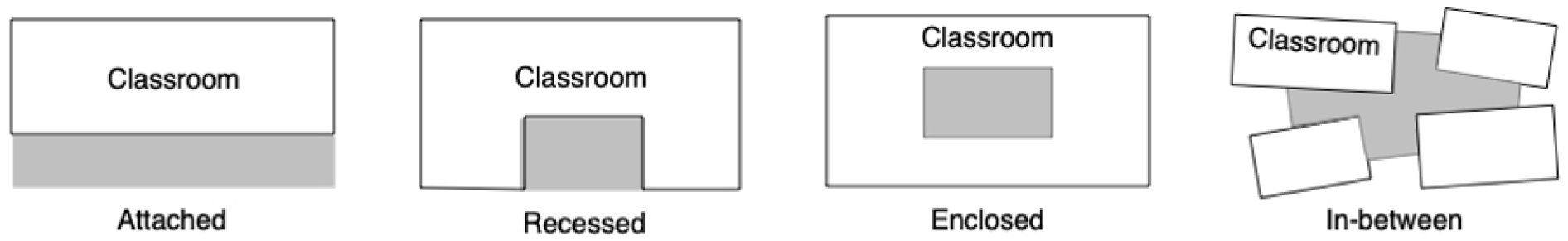

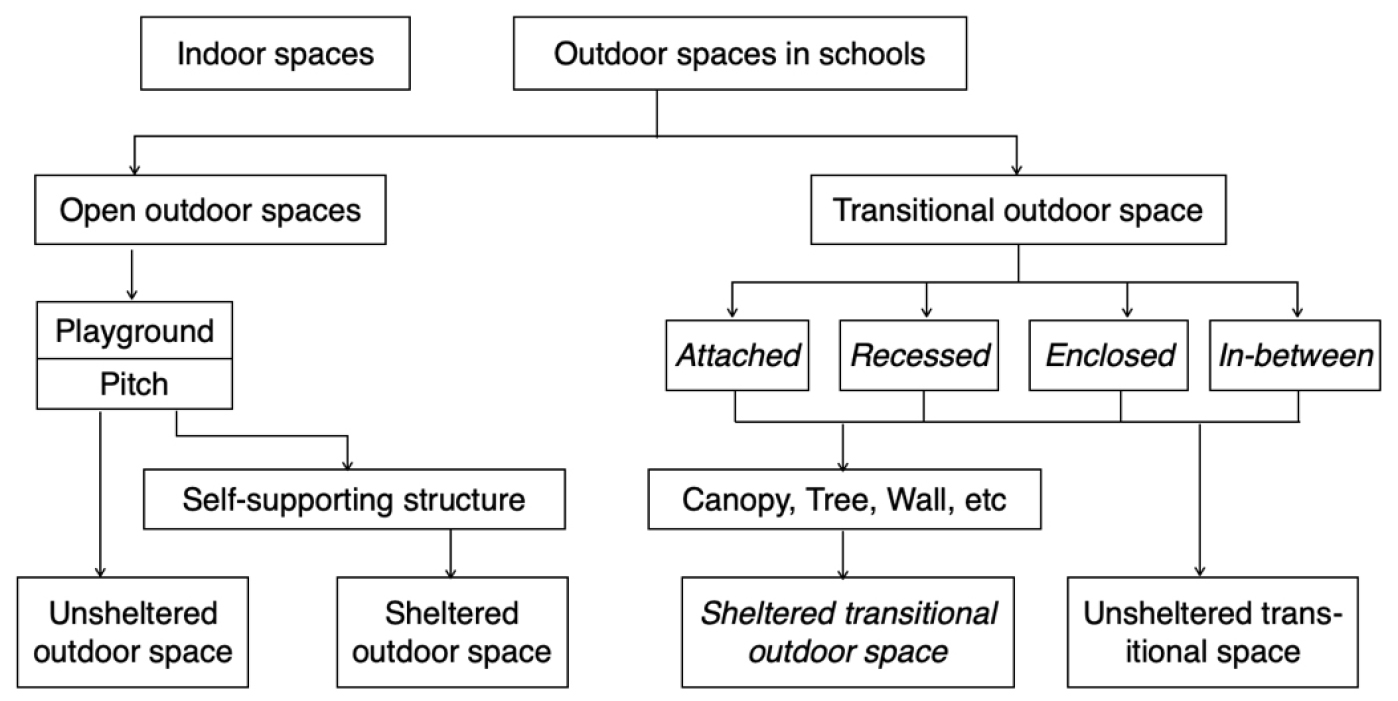

The different types of transitional spaces can be categorised by the relationship between buildings and outdoor spaces. An outdoor space can be enclosed and include walls, roofs and floor but at least one side should be exposed to the outside air, which defined as the adjacent space. Depending on the form of enclosure and layout, they can be grouped into three basic types: attached, recessed and enclosed as well as in-between types as shown in Figure 5 and real building examples of the different types of transitional space are given in Figure 6.

An attached type is a transitional space covered by an extended roof or set back from the street, attached to classrooms or buildings. The veranda is a typical form of attached space in houses or schools. This is a roofed platform along the outside of a building which sometimes has different flooring material or is on a different level to the outdoor grounds. The most popular form of attached outdoor classroom is a linear sheltered space alongside a rectangular plan building (Figures 5(a) and 6(a)) and this is commonly found as a feature of refurbished school buildings. This space can be integrated as a veranda by providing roofs and platforms that can be used for circulation, eating, chatting and relaxing as well as being a sheltered and shaded space from unwanted rain and solar sunshine.

A recessed type of sheltered transitional space is set into the middle portion of the facade of a similar rectangular building (Figures 5(b) and 6(b)). It is already enclosed on three sides and provides a cosy and protected space apart from the outdoor open space. This form can provide a diverse range of outdoor spaces through seamlessly connecting each space (open, semi-open). A recessed transitional space can be created by adding a covering roof or fence in which a more secured space can be provided than an open outdoor space.

Courtyards, a form of transitional space with an enclosed shape, are commonly found in countries with Mediterranean climates, where they provide a thermal refuge from the building [15]. As they are enclosed by buildings, courtyards provide private and sheltered outdoor places disconnected from the outer school buildings as seem in Figures 5(c) and 6(c). These places are protected against noise and from being overlooked by neighbours so can help teachers to carry out the school curriculum effectively. With the addition of some particular features (e.g., covered roof, trees, etc) courtyards can provide a pleasant outdoor environment and can also improve indoor thermal conditions. However, other features, for example paving or covered ground, may lead to an increase in the indoor temperature of the buildings around them and cause poor ventilation to the rooms located on the leeward side [15, 16].

The in-between type as shown in Figures 5(d) and 6(d) is one where a transitional space is located in between buildings or blocks situated in a generally covered space which connects the buildings; it can be used as a public meeting place. A wide corridor where multiple activities can take place is a feature of this type. The central area is often used as an atrium, joining two blocks of classrooms and providing public space with enough daylight. The roof-covered space, while open at the ends, can provide solar control over the in-between space in warm periods. It is normally wide enough to host many different activities beyond its function as a protected circulation path for the school and is used for a number of public functions.

Figure 7 shows the analytical classification of the types of outdoor space in schools in this research. The areas outside a school building can be generally categorised as “outdoor spaces” and “transitional spaces” depending on the proximity of the buildings. Transitional spaces can be divided into four different types by shape in relation to the main buildings. This will be studied in detail in the next section. Building elements or landscaping can provide shelters for the transitional space, which can then be referred to as “sheltered transitional spaces”. Therefore, the outdoor spaces in schools can be categorised into four types according to whether the space is sheltered or not and the proximity of buildings: Open (unsheltered) outdoor space, sheltered outdoor space, sheltered transitional space and open (unsheltered) transitional space.

Conclusions

This research provides a literature review of some architectural perspectives, studying transitional spaces in schools looking at particular architectural characteristics of such spaces and giving selected examples of both contemporary and historical projects.

Some findings are summarised as follows.

‧Outdoor spaces are an important part of the school environment. From a pedagogical point of view, they are useful as outdoor classrooms or play areas protected from rain or sunlight and have a particularly important role in allowing pupils to interact with nature as a part of their education. They therefore have particular architectural requirements.

‧Sheltered transitional spaces can be defined as the partly covered areas in places immediately adjacent to the buildings.

‧Semi-sheltered spaces have proved popular in schools built recently, in particular the exemplar schools of the DfES. However, adding partly or mostly covered spaces with less careful design can lead to poor outdoor environment and also deterioration in the indoor environment, which leads to consumption of a huge amount of energy for heating or lighting.

‧There is a wide diversity of architectural elements (e.g., canopies, awnings, trees, etc) used to provide environmental shelters both indoor and outdoor spaces.

‧The environmental functions of the canopy with different depth and width (e.g., open or partly open type of cover canopy), the main building device operate in conjunction with the architectural concept of combining indoor and outdoor spaces.

‧The devices can help to lessen the undesirable effects of the outdoor environment and also to influence the indoor energy demand.

The examples given show the four typologies of semi-sheltered spaces in which designers have tried to connect outdoor spaces with the indoor buildings thus promoting the use of external spaces as a part of school activities and also enhancing the school aesthetics. The environmental methods used to support the architectural concept of combining outdoor and indoor spaces need to be considered carefully for the enhanced performance [17]. Allowing a building to embrace its climate context has the power to enrich the architectural experience as well as to enhance outdoor experience in school. It is clear that the more widespread adoption of climatically responsive thinking by contemporary designers ought to have the welcome effect of prompting a more diverse range of environmental strategies and thus site-specific buildings are necessary.