Introduction

Literature Review

Impact of University Library Space Utilization on Learning Experience

Impact of Informal Learning Needs on Learning Experience

Mediating Role of Learning Space Satisfaction

Theoretical Model and Research Framework

Theoretical Model Development

Research Hypotheses and Theoretical Model Framework

Methodology

Research Design

Participants and Data Collection

Measurement

Data Analysis

Data Results and Analysis

Sample Characteristics

Reliability Analysis and Validity Analysis

Correlation Analysis Results

Regression Analysis Results

Mediating Effect

Discussion

Key Findings and Interpretations

Comparison with Prior Studies

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Conclusion

Introduction

In the modern academic environment, libraries have evolved from mere information repositories into comprehensive learning spaces that support student development. Learning satisfaction is a crucial indicator of students’ perceptions of their learning experience and environment. High learning satisfaction indicates that the library has successfully adapted to this transformation, providing an environment conducive to student learning [1]. Therefore, investigating users’ learning satisfaction not only helps assess the effectiveness of current services but also enhances understanding and responsiveness to student needs, allowing for more tailored future space design and service provision.

University library learning spaces are integral to students’ learning experiences and academic performance. With changes in educational approaches, library learning environments have shifted from traditional fixed spaces to flexible and diverse environments that cater to students’ evolving needs [2]. These learning spaces extend beyond physical areas, encompassing social and emotional support systems that facilitate learning, communication, and collaboration [3]. This recognition underscores the potential role of library learning spaces in enhancing student learning satisfaction, highlighting the importance of examining the impact of learning space utilization on learning behaviors.

The effectiveness of university library learning spaces is influenced by multiple factors, including frequency of access, duration of use, and students’ spatial preferences. Research indicates that the more time students spend in library learning spaces, the higher their satisfaction levels [4]. Additionally, allowing students to choose their preferred learning environment enhances their autonomy and overall satisfaction, thereby improving learning outcomes [5].

Another key factor influencing learning satisfaction is the fulfillment of informal learning needs. Informal learning activities, such as collaborative learning, independent study, and social interaction, are crucial for enriching students’ learning experiences. Collaborative learning promotes engagement and interaction, independent study spaces support personalized learning, and social interaction areas help foster motivation and a sense of belonging [6, 7]. Understanding how these informal needs affect learning satisfaction and behavior is essential for designing optimal learning spaces.

Against this backdrop, the present study aims to explore the complex relationships among the use of university library learning spaces, the fulfillment of informal learning needs, and learning satisfaction. Specifically, we seek to address the following research questions:

(1)How does the use of university library learning spaces affect students’ learning satisfaction?

(2)How do informal learning needs (e.g., collaborative learning, independent study, and social interaction) impact students’ learning satisfaction?

(3)Does learning space satisfaction mediate the relationship between library space usage, informal learning needs, and learning satisfaction?

Although university libraries have made significant progress in transforming into dynamic learning environments, there is still a lack of understanding of how these learning spaces impact overall student learning satisfaction. This study fills this gap by exploring the utilization of learning spaces in university libraries, the satisfaction of informal learning needs, and their relationship with students’ overall learning satisfaction, and analyzes the relationship between learning space satisfaction among these factors. intermediary role. The findings provide practical insights into how library spaces can be optimized to improve student satisfaction and academic outcomes, helping universities create more inclusive and supportive environments for student learning. This study not only provides theoretical support for learning environment design, but also helps improve student satisfaction and academic performance through optimized design.

Literature Review

Impact of University Library Space Utilization on Learning Experience

The impact of university library space utilization on students’ learning experiences is a well-researched area of interest. Existing literature indicates that factors such as choice of learning space, frequency of access, and duration of use significantly affect students’ learning outcomes. Through in-depth analysis of space utilization patterns, studies have shown that the design of learning spaces directly influences students’ learning satisfaction, concentration, and academic performance [8].

First, students exhibit different needs for learning spaces depending on their activities. Beckers et al. (2016) found that students engaging in individual study tend to prefer quiet and private learning spaces to minimize distractions and enhance concentration [9]. For collaborative learning activities, students prefer open and flexible spaces that facilitate interaction. Scoulas & Groote (2019) further validated this by highlighting that students select quiet areas or collaborative zones within the library based on their specific learning needs, and this flexibility enables libraries to effectively support diverse learning activities [8]. Additionally, Wang & Han (2021) pointed out significant differences in learning space preferences among students with different learning styles. For example, visual learners tend to prefer multimedia rooms, while students who favor independent study prefer quiet areas [10]. Therefore, university library space design should emphasize diversity to meet the needs of different types of students.

Second, the physical characteristics of learning spaces significantly impact students’ learning experiences. Min & Lee (2020) studied students’ selection of individual study spaces in digital reading rooms and found that students preferred seats with privacy and access to power outlets, particularly those located against walls or in corners, as such arrangements help improve focus [11].

Moreover, the flexibility and adaptability of space design are critical factors influencing the learning experience. Bussell (2021), in a study of a university library in Norway, found significant variations in students’ learning space needs throughout the semester, indicating that flexible learning space configurations, such as movable furniture and reconfigurable seating arrangements, better accommodate students’ changing learning needs [12]. Similar conclusions were drawn by May & Swabey (2015) in a multi-site observational study, emphasizing that library spaces should support both individual study in quiet environments and collaborative learning in open areas to meet the diverse needs of students [13].

Furthermore, the location of learning spaces significantly affects students’ class participation and academic performance. Shernoff et al. (2017) found that students sitting at the front of classrooms exhibited higher levels of engagement and academic achievement, indicating that spatial arrangement is crucial for learning efficiency [14]. Therefore, libraries should consider seating arrangements in space planning to promote student engagement and learning outcomes.

In summary, the design and utilization of university library spaces have a significant impact on students’ learning experiences. By providing diverse, flexible, and adaptable learning spaces that cater to different learning styles and activity needs, libraries can significantly enhance students’ learning satisfaction and academic performance. These findings provide valuable insights for the planning of university library spaces, helping create more efficient and comfortable learning environments for students.

Impact of Informal Learning Needs on Learning Experience

Informal learning needs play a vital role in learning environments such as university libraries, significantly affecting learning satisfaction and outcomes. These needs are generally categorized into collaborative needs, independent learning needs, and social interaction needs [15].

Collaborative needs typically require group study spaces to support team projects and discussion activities. To make these spaces effective, recent studies have emphasized the importance of flexibility and responsiveness to both structured and spontaneous interactions [3].

In contrast, independent learning needs favor quiet, private study areas that help students focus deeply and think critically. Such environments promote autonomy, enabling students to effectively manage their learning processes. For students who prefer independent study, a quiet, private, and distraction-free environment is closely linked to higher satisfaction levels [4]. DeFrain & Hong (2020), in their study on university shared learning spaces, found that these environments provide a setting that supports independent study while also fostering social connections [16]. Although many students prefer to complete independent tasks in shared learning spaces, opportunities for social interaction enhance overall learning satisfaction. Therefore, the design of learning spaces should balance quiet and collaborative functions to ensure that students can flexibly meet different learning needs.

Social interaction needs reflect students’ desire to engage in social interactions during the learning process, which can be fulfilled through open, communication-friendly learning spaces. Social interaction spaces play a unique role in supporting informal learning by fostering a sense of belonging and community, which is crucial for maintaining motivation and reducing academic isolation [17, 18]. Studies have shown that social spaces in academic environments enhance students’ well-being and facilitate informal exchanges, thereby supporting the overall learning experience [3, 15].

Understanding these needs can help libraries and educational institutions better configure different types of learning areas to accommodate students’ diverse learning styles. Informal learning, encompassing self-directed group learning and social learning activities, also plays an important role in building community within academic environments.

Mediating Role of Learning Space Satisfaction

Learning space satisfaction plays a mediating role between the use of learning spaces, informal learning needs, and overall learning satisfaction. The relevant literature supports the crucial role of learning space satisfaction in shaping the learning experience. Wang and Han (2021) explored how students’ learning styles and space preferences influence their satisfaction with learning spaces [10]. Their study found that students with different learning styles have distinct spatial needs; for instance, visual learners prefer multimedia classrooms, while independent learners favor study rooms. Learning space designs that meet these personalized needs enhance learning space satisfaction, which, in turn, positively influences overall learning satisfaction. Learning space satisfaction, as a mediating variable, links spatial characteristics to students’ overall learning satisfaction, thereby fostering a better learning experience.

Chin et al. (2021) further highlighted that the modern educational environment has shifted from a traditional teacher-centered model to a student-centered approach, leading to increasingly diverse informal learning needs [19]. Chin’s study, which established a classification framework for informal learning spaces, revealed the critical role of various types of learning spaces in meeting collaborative, social, and independent learning needs. The design of these informal learning spaces not only satisfies social and collaborative needs but also enhances overall learning experiences and outcomes by improving satisfaction with learning spaces. Scannell et al. (2016) examined the influence of acoustic environments and spatial design characteristics on students’ adaptability and well-being in informal learning settings [20]. Their findings indicated that reducing background noise, adding soft furnishings, and incorporating greenery significantly improved students’ adaptability and satisfaction with space use. This increased satisfaction not only directly impacted learning efficiency but also indirectly enhanced overall learning satisfaction through improved use of space.

In summary, learning space satisfaction plays an essential mediating role between the use of learning spaces, informal learning needs, and overall learning satisfaction. Space designs that meet personalized needs and informal learning demands can enhance learning space satisfaction, which in turn improves students’ overall learning experience and satisfaction. As a mediating factor, learning space satisfaction closely connects the characteristics of the physical environment, behavioral needs, and students’ subjective learning experiences, highlighting the key role of learning spaces in supporting modern educational goals.

Theoretical Model and Research Framework

Theoretical Model Development

This study constructs a theoretical model based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT).

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) emphasizes the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in motivation. The design of learning spaces should consider how to meet these three fundamental psychological needs to enhance students’ learning experiences. For example, a space that allows students to freely choose their learning location and method can enhance their sense of autonomy and motivation. Additionally, learning spaces that support students in effectively completing their tasks (e.g., providing appropriate tools and environments) can increase their sense of competence. Collaborative learning spaces and social interaction areas can fulfill students’ need for relatedness, giving them a sense of connection with others. In this study, SDT provides a theoretical basis for understanding how learning spaces influence students’ learning satisfaction.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) emphasizes the interaction between environment, personal factors, and behavior. According to SCT, learning spaces are not just physical environments; they also encompass social settings and interpersonal interactions. In learning spaces, students’ learning behaviors are influenced by their perception of the environment and their interactions with others. For instance, collaborative learning spaces can facilitate knowledge sharing and social interaction among students, thereby enhancing learning outcomes. In this study, SCT provides a framework for exploring how informal learning needs influence overall learning satisfaction through learning space satisfaction.

Through the lens of these theories, satisfaction with library spaces serves as an important mediator between space usage and overall learning satisfaction, reflecting the effectiveness of library environments in meeting students’ psychological and social needs.

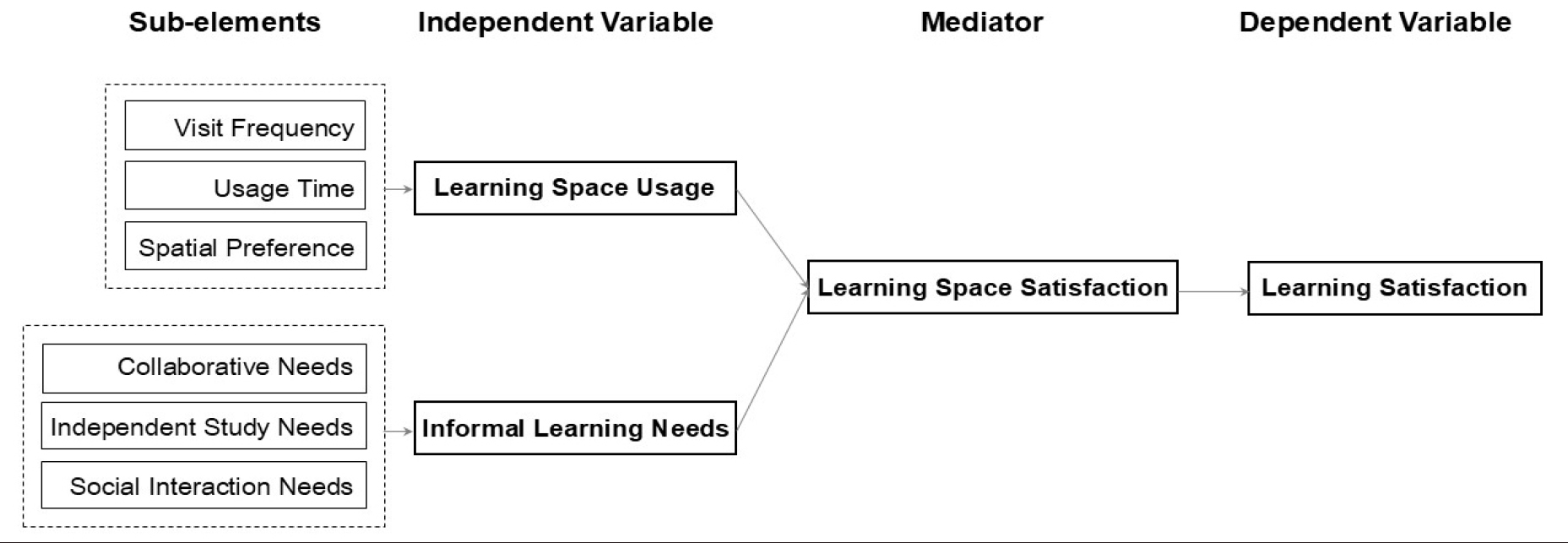

Research Hypotheses and Theoretical Model Framework

Based on the literature review and the aforementioned theoretical models, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

(1)Hypothesis 1: The higher the frequency, duration, and satisfaction with spatial preferences of learning space usage, the more positive the impact on overall satisfaction with library spaces.

(2)Hypothesis 2: The better the fulfillment of different informal learning needs, the more positive the impact on overall satisfaction with library spaces.

(3)Hypothesis 3: Learning space satisfaction mediates the relationship between space usage, informal learning needs, and overall learning satisfaction, with learning space satisfaction having a significant positive effect on learning satisfaction.

By integrating Self-Determination Theory and Social Cognitive Theory, this study constructs a model framework (Table 1) that demonstrates how learning space satisfaction mediates the relationship between learning space usage, informal learning needs, and learning satisfaction. This framework emphasizes the importance of well-designed, adaptable environments in meeting students’ functional, psychological, and social needs, thereby promoting a more satisfying and productive learning experience.

Methodology

Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative cross-sectional survey design to explore the relationships among learning space usage, informal learning needs, learning space satisfaction, and overall learning satisfaction. Based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), a theoretical model was constructed, hypothesizing that learning space satisfaction mediates the effects of learning space usage and informal learning needs on overall learning satisfaction. The quantitative approach enables empirical testing of the model and facilitates structured and rigorous analysis of the hypothesized relationships.

Participants and Data Collection

The sample of this study comprised 316 university students from different academic stages and disciplines, ensuring diversity in experiences and perspectives related to library use and satisfaction. Participants were recruited through two methods: offline recruitment at the university library and online recruitment via the university management platform over a four-week period, ensuring broad and inclusive participation.

A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data on four main constructs: learning space usage, informal learning needs, learning space satisfaction, and overall learning satisfaction. To ensure the reliability and validity of the measurements, the questionnaire items were adapted from previously validated scales. Each item was structured to capture key dimensions of the constructs, including frequency of access, duration of use, spatial preferences, collaborative needs, independent study needs, social interaction needs, and overall satisfaction with the library learning experience.

Measurement

Each main construct was measured through its respective dimensions to provide a comprehensive assessment:

•Learning Space Usage: This independent variable includes three dimensions: frequency of access, duration of use, and spatial preferences. These dimensions capture students’ behavioral interactions within the learning spaces.

•Informal Learning Needs: This construct includes three dimensions—collaborative needs, independent learning needs, and social interaction needs. These dimensions reflect the multifunctional and social demands students have for learning spaces.

•Space Satisfaction: As a mediating variable, this was assessed through comfort, resource availability, and accessibility of spaces. These dimensions align with the principles of SDT and SCT, evaluating the extent to which the learning environment meets students’ psychological and functional needs.

•Learning Satisfaction: As the dependent variable, it measures students’ overall satisfaction with their library learning experience. This variable reflects the cumulative impact of learning space usage, informal learning needs, and space satisfaction on students’ academic experience.

Each construct was evaluated using multiple items rated on a Likert scale, allowing for detailed analysis of students’ perceptions and behaviors related to library use. The reliability and validity of each scale were subsequently evaluated in the data analysis phase.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software to assess the reliability, validity, correlations, and mediation effects among the study variables. First, internal consistency of each measurement scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with values above 0.7 indicating good reliability. To ensure construct validity, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test were conducted. A KMO value above 0.6 indicated adequate sampling, and factor loadings greater than 0.4 were used to validate the dimensions of each construct.

Next, correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships among learning space usage, informal learning needs, learning space satisfaction, and overall learning satisfaction. Hierarchical regression analysis was then conducted to evaluate the predictive power of the independent variables (learning space usage and informal learning needs) on learning space satisfaction and overall learning satisfaction. By controlling for other variables, each factor’s contribution was analyzed step by step.

Finally, the mediation effect of learning space satisfaction was tested using the method proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). This method involves analyzing the direct, indirect, and total effects of learning space usage and informal learning needs on learning satisfaction to determine the presence of mediation [21]. To enhance the robustness of the mediation analysis, the Bootstrap method (with 5000 iterations and a 95% confidence interval) was employed to provide accurate estimates of indirect effects and strengthen the reliability of the mediation results. This structured approach to data analysis ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed model and hypothesized relationships.

Data Results and Analysis

Sample Characteristics

Based on the survey results presented in the below table (Table 2), a total of 316 participants were involved in this study. The gender distribution is relatively balanced, with males accounting for 52.85% (167 individuals) and females accounting for 47.15% (149 individuals). This data indicates that the proportion of males and females in the sample is relatively similar, suggesting an active participation from both genders in the survey. Regarding age distribution, participants aged 18-22, 23-26, and 27 and above account for 32.91% (104 individuals), 33.86% (107 individuals), and 33.23% (105 individuals), respectively. This shows that students from different age groups were well- represented, with a relatively even distribution, ensuring that the study comprehensively covers the learning circumstances of students across various age groups.

Table 2.

The Table of Sample Characteristics

In terms of educational level, undergraduates constitute 30.06% (95 individuals), master’s students account for 23.42% (74 individuals), doctoral students make up 21.84% (69 individuals), and other education levels represent 24.68% (78 individuals). This result reflects the diversity of educational backgrounds among the sample, ranging from undergraduate to doctoral levels, providing a broad foundation for analyzing learning behaviors. Regarding the preferred study locations, the survey results show that classrooms are the most popular study setting, accounting for 32.60% (103 individuals), indicating that students prefer studying in a classroom environment. This is followed by libraries (26.90%), dormitories (24.37%), and coffee shops (16.14%). This reflects students’ preferences when choosing study environments, which are influenced by factors such as study atmosphere and social interaction.

For study tools, the choices of participants also show diversity. Printed books were preferred by 29.43% (93 individuals), computers/tablets were chosen by 25.32% (80 individuals), e-books by 24.68% (78 individuals), and mobile applications by 20.57% (65 individuals). This data indicates that, despite the increasing prevalence of digital learning tools, printed books remain an important resource for learning, reflecting students’ reliance on traditional study materials.

Reliability Analysis and Validity Analysis

Reliability, also referred to as consistency, represents the degree to which a questionnaire yields trustworthy and reproducible results, indicating the stability and consistency of measurements over time. A reliable measurement tool should consistently yield the same results when applied repeatedly to the same subject. This study employs Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient to assess the internal consistency of the scale, which is currently one of the most widely used methods in empirical research. The calculation formula for α is as follows:

where k denotes the number of items in the questionnaire, σi2 represents the variance of the response for item i, and σ2 is the variance of the total responses. A higher α value indicates greater consistency among the items, which in turn suggests higher reliability of the scale. Common thresholds for evaluating reliability are as follows: an α value below 0.6 indicates low reliability, suggesting a need for revision of the questionnaire or removal of problematic items. Values between 0.7 and 0.8 indicate acceptable reliability, while a value above 0.9 suggests excellent stability and consistency of the measurement.

In this study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire, ensuring the reliability of each construct. The results showed that all constructs had Cronbach’s α values above 0.6, indicating high internal consistency. Specifically, most dimensions had α values close to or above 0.7, reflecting good consistency among the measurement items and relatively high reliability. Particularly for the measurement of learning space satisfaction, informal learning needs, and overall learning satisfaction, the α values were close to 0.8 to 0.9, indicating that these scales have high stability and reliability in assessing the relevant constructs.

In conclusion, the measurement tools used in this study showed good internal consistency, indicating that they are suitable for measuring university students’ learning space usage, informal learning needs, and learning satisfaction.

Validity refers to the extent to which a comprehensive evaluation system accurately reflects the intended purpose and requirements of the evaluation. In this study, construct validity was assessed using factor analysis, which is commonly used to evaluate the underlying structure of a measurement scale.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to determine whether the measurement items exhibit consistent and stable relationships with the latent variables they are intended to measure. Two conditions are generally required to conduct factor analysis: (1) a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value greater than 0.7 and (2) a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity with a p-value less than 0.05. The KMO and Bartlett’s test results are summarized below Table 3.

Table 3.

The Table of Validity Analysis Results

| KMO and Bartlett’s test | ||

| KMO | 0.965 | |

| Bartlett’s Test | Approx. χ2 | 23682.304 |

| df | 1128 | |

| p-value | 0.000 | |

The results indicate that the factor analysis is suitable for the dataset, with a KMO value of 0.965 (>0.6) and a significant Bartlett’s test result (p < 0.001). This confirms the appropriateness of conducting principal component analysis on the scale.

Correlation Analysis Results

As shown in Table 4, there is a significant positive correlation between learning satisfaction, space use satisfaction, and other variables, indicating the mutual influence of factors in students’ learning experiences. Specifically, the correlation between learning satisfaction and space use satisfaction is 0.462 (p < 0.01), suggesting that higher satisfaction with learning space leads to increased overall learning satisfaction. This relationship also extend to social interaction needs and independent learning needs, with correlations of 0.470 and 0.440, respectively. This implies that learners are more likely to achieve high levels of learning in environments that meet their spatial needs.

Table 4.

The Table of Correlation Analysis Results

| Learning Satisfaction | Space Use Satisfaction | Social Interaction Needs | Independent Learning Needs | Collaborative Learning Needs | Space Preference | Usage Time | Visit Frequency | |

| Learning Satisfaction | 1 | |||||||

| Space Use Satisfaction | 0.462*** | 1 | ||||||

| Social Interaction Needs | 0.470*** | 0.444*** | 1 | |||||

| Independent Learning Needs | 0.440*** | 0.474*** | 0.481*** | 1 | ||||

| Collaborative Learning Needs | 0.385*** | 0.465*** | 0.382*** | 0.516*** | 1 | |||

| Space Preference | 0.417*** | 0.440*** | 0.391*** | 0.410*** | 0.404*** | 1 | ||

| Usage Time | 0.489*** | 0.416*** | 0.380*** | 0.430*** | 0.465*** | 0.435*** | 1 | |

| Visit Frequency | 0.450*** | 0.436*** | 0.439*** | 0.434*** | 0.419*** | 0.425*** | 0.403*** | 1 |

Significant correlations are also observe between social interaction, independent learning, space use satisfaction, and social interaction needs (0.444, p < 0.01) and independent learning needs (0.474, p < 0.01). These findings emphasize the importance of a well-designed learning environment. When learning spaces are optimized to support social and independent learning, students’ needs are effectively met, thereby enhancing their learning satisfaction. This outcome highlights the necessity for educators to improve learning environment design to directly enhance students’ learning experiences and achievements.

Space preference and usage time are also find to have significant effects on learning satisfaction. The correlation coefficient between space preference and learning satisfaction is 0.417 (p < 0.01), while the coefficient for usage time and learning satisfaction is 0.489 (p < 0.01). This suggests that learners’ decisions regarding space selection and time investment have a direct impact on their learning satisfaction. Learners tend to choose environments aligned with their personal preferences and invest more time in these settings, thereby enhancing their learning effectiveness and overall satisfaction.

In conclusion, learning satisfaction and space use satisfaction constitute the core elements of students’ learning experiences. They are closely related to social interaction needs, independent learning needs, and collaborative learning needs, collectively shaping the learning environment and outcomes for students.

Regression Analysis Results

The regression analysis aimed to explore the relationships between learning space usage, informal learning needs, and their impact on space satisfaction and overall learning satisfaction. The analysis was divided into three main components: learning space usage and space satisfaction, informal learning needs and space satisfaction, and space satisfaction as a mediator for overall learning satisfaction.

The Relationship between Space Use Situation and Space Use Satisfaction

The first model assessed the influence of learning space usage factors, including frequency of visits, time spent, and spatial preferences, on space satisfaction. The regression results (as shown in Table 5) indicated that all three factors had significant positive impacts on space satisfaction. Specifically, the model had an R² value of 0.302, indicating that these factors explained 30.2% of the variance in space satisfaction (F = 45.061, p < 0.01).

Table 5.

The Regression Analysis Results of the Relationship between Space Use Situation and Space Use Satisfaction

|

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients | t | p |

Collinearity Diagnostics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | VIF | Tolerance | |||

| Constant | 0.310 | 0.201 | - | 1.543 | 0.124 | - | - |

| Frequency of Visits | 0.259 | 0.057 | 0.248 | 4.570 | 0.000*** | 1.314 | 0.761 |

| Usage Time | 0.229 | 0.059 | 0.211 | 3.865 | 0.000*** | 1.328 | 0.753 |

| Spatial Preference | 0.292 | 0.066 | 0.243 | 4.404 | 0.000*** | 1.358 | 0.736 |

| R2 | 0.302 | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.296 | ||||||

| F | 45.061*** | ||||||

| D-W Value | 2.161 | ||||||

Visit Frequency: The regression coefficient for visit frequency was 0.259 (t = 4.570, p < 0.01), suggesting that more frequent visits were associated with higher satisfaction. This finding highlights that students who frequently use the library become more familiar with the environment, increasing their sense of comfort and satisfaction.

Time Spent: Time spent in the learning space also positively affected satisfaction, with a regression coefficient of 0.229 (t = 3.865, p < 0.01). Longer time spent was linked to increased satisfaction, reflecting that students who invest more time experience greater benefits from the space, including academic support and productivity.

Spatial Preferences: Spatial preferences had the highest impact, with a coefficient of 0.292 (t = 4.404, p < 0.01). Students who used spaces that matched their individual learning needs reported higher satisfaction, underlining the importance of personalized learning environments.

These results collectively demonstrate that frequent use, time invested, and alignment with spatial preferences significantly contribute to the overall satisfaction of library spaces, emphasizing the need for adaptable and inclusive learning environments.

These results collectively demonstrate that frequent use, time invested, and alignment with spatial preferences significantly contribute to the overall satisfaction of library spaces, emphasizing the need for adaptable and inclusive learning environments.

The Relationship between Informal Learning Needs and Space Satisfaction

The second model examined the relationship between informal learning needs—collaborative learning, independent study, and social interaction—and space satisfaction. The model (Table 6) had an R² value of 0.333, explaining 33.3% of the variance in space satisfaction (F = 51.832, p < 0.01).

Table 6.

The Regression Analysis Results of the Relationship between Informal Learning Needs and Space Satisfaction

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p |

Collinearity Diagnostics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | VIF | Tolerance | |||

| Constant | 0.716 | 0.156 | - | 4.587 | 0.000*** | - | - |

| Collaborative Learning Needs | 0.225 | 0.048 | 0.257 | 4.692 | 0.000*** | 1.407 | 0.711 |

| Independent Learning Needs | 0.231 | 0.059 | 0.228 | 3.939 | 0.000*** | 1.563 | 0.640 |

| Social Interaction Needs | 0.242 | 0.055 | 0.236 | 4.409 | 0.000*** | 1.343 | 0.745 |

| R2 | 0.333 | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.326 | ||||||

| F | 51.832*** | ||||||

| D-W Value | 2.025 | ||||||

Collaborative Learning Needs: The coefficient for collaborative learning needs was 0.225 (t = 4.692, p < 0.01). Students who valued collaborative opportunities were more satisfied when such environments were available. This highlights the importance of providing spaces designed for group work, such as discussion rooms or shared study areas, which facilitate peer learning and enhance satisfaction.

Independent Learning Needs: The regression coefficient for independent learning needs was 0.231 (t = 3.939, p < 0.01). The significance of this factor suggests that students seeking quiet, solitary study areas experience higher satisfaction when their needs for privacy and focus are met. This reinforces the need for diverse learning spaces that support different learning styles.

Social Interaction Needs: The coefficient for social interaction needs was 0.242 (t = 4.409, p < 0.01), indicating that students who engaged in or valued social interactions within the library had higher satisfaction levels. This emphasizes the dual role of learning spaces in supporting both academic and social needs, thus fostering a sense of community and belonging.

The analysis reveals that fulfilling informal learning needs significantly enhances space satisfaction, and this relationship is pivotal for designing multifunctional library spaces that cater to a diverse student body.

The Relationship between Space Satisfaction and Learning Satisfaction

The final model assessed the direct impact of space satisfaction on overall learning satisfaction. The regression analysis yielded an R² value of 0.213, indicating that space satisfaction explained 21.3% of the variance in learning satisfaction (F = 85.095, p < 0.01). The coefficient for space satisfaction was 0.504 (t = 9.225, p < 0.01), suggesting a strong positive effect (as shown in Table 7).

Table 7.

The Regression Analysis Results of the Relationship between Space Satisfaction and Learning Satisfaction

|

Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p |

Collinearity Diagnostics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | VIF | Tolerance | |||

| Constant | 1.665 | 0.147 | - | 11.289 | 0.000*** | - | - |

| Space Use Satisfaction | 0.504 | 0.055 | 0.462 | 9.225 | 0.000*** | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| R2 | 0.213 | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.211 | ||||||

| F | 85.095*** | ||||||

| D-W Value | 2.009 | ||||||

This finding underscores that a positive perception of learning spaces translates to an increase in students’ overall satisfaction with their learning experience. Space satisfaction reflects students’ evaluation of the environment’s comfort, accessibility, and utility in meeting their academic needs. Enhancing these aspects not only motivates students to engage more deeply with their studies but also positively affects academic outcomes.

Mediating Effect

When examining the effect of independent variable X on dependent variable Y, if X influences Y through a mediating variable M, M is considered the mediator. The following regression equations describe the relationships between the variables:

In these equations, c in equation (1) represents the total effect of X on Y; a in equation (2) indicates the effect of X on the mediator M; b in equation (3) is the effect of M on Y while controlling for X; c' represents the direct effect of X on Y when M is controlled; and e1 through e3 are the residual errors.

To test whether space use satisfaction plays a significant mediating role between space usage, informal learning needs, and overall satisfaction, this study follows the mediation analysis procedure proposed by Wen and Ye (2014). The steps of this mediation analysis are as follows:

Step 1. Test coefficient c in equation (1). If significant, it indicates mediation; otherwise, suppression is considered. Regardless of significance, continue with the next steps.

Step 2. Test coefficient a in equation (2) and b in equation (3). If both are significant, it suggests a significant indirect effect, proceed to Step 4. If either is not significant, proceed to Step 3.

Step 3. Use the Bootstrap method to directly test H0: ab = 0. If significant, the indirect effect is confirmed; otherwise, there is no significant mediation, and analysis stops.

Step 4. Test coefficient c' in equation (3). If c' is not significant, only the indirect effect exists. If significant, proceed to Step 5.

Step 5. Compare the signs of ab and c'. If they have the same sign, it indicates partial mediation, and the proportion of the mediation effect is reported as ab/c. If the signs differ, it indicates suppression, and the absolute ratio |ab/c'| is reported.

This structured approach ensures precise testing of the mediating effect and distinguishes between different types of mediation and suppression effects.

The results of Table 8 indicated a partial mediation effect:

Table 8.

The Table of Mediating Effect Analysis Results

Learning Space Usage → Space Satisfaction → Learning Satisfaction: The total effect of learning space usage on learning satisfaction was significant (c = 0.613, p < 0.01), with an indirect effect via space satisfaction (a*b = 0.065, 95% CI [0.005, 0.082]). The direct effect remained significant (c' = 0.548, p < 0.01), indicating partial mediation.

Informal Learning Needs → Space Satisfaction → Learning Satisfaction: Similarly, the total effect of informal learning needs on learning satisfaction was significant (c = 0.355, p < 0.01), with an indirect effect through space satisfaction (a*b = 0.071, 95% CI [0.006, 0.106]). The direct effect also remained significant (c' = 0.284, p < 0.01).

These findings confirm that space satisfaction plays a significant mediating role in the relationships between both learning space usage and informal learning needs with overall learning satisfaction. The results highlight the critical role of designing and managing learning environments that effectively address students’ diverse needs to enhance their overall academic experience.

Discussion

Key Findings and Interpretations

The current study examined the relationships between learning space usage, informal learning needs, learning space satisfaction, and overall learning satisfaction. One key finding was that both the frequency and duration of learning space usage, as well as students’ spatial preferences, significantly influenced learning space satisfaction, which in turn positively impacted overall learning satisfaction. This finding has practical implications for universities, suggesting that they should prioritize providing flexible and accessible learning spaces that students can use frequently and for extended periods. For example, universities could extend library hours or enhance seating availability to accommodate peak usage times, thereby ensuring that students have adequate opportunities to utilize these spaces according to their preferences.

Another critical finding was that the fulfillment of informal learning needs—including collaborative, independent, and social interaction needs—had a substantial impact on learning space satisfaction. Specifically, spaces designed to support these different types of informal learning activities were shown to enhance satisfaction, ultimately leading to greater learning satisfaction. This suggests that learning environments that accommodate a range of learning styles and needs can foster a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, positively influencing students’ motivation and learning outcomes. Practically, universities could implement more diverse learning spaces, such as group study rooms, quiet areas, and informal social spaces, to ensure that students have access to spaces that suit their varied needs. This approach not only enhances individual satisfaction but also supports broader institutional goals of promoting student engagement and academic success.

Furthermore, the study demonstrated the mediating role of learning space satisfaction between the use of learning spaces, informal learning needs, and overall learning satisfaction. Learning space satisfaction effectively linked students’ physical environment interactions to their subjective learning experiences, emphasizing the need for well-designed spaces that meet both psychological and functional requirements. This finding highlights the importance of strategic space planning in higher education institutions. By adopting evidence- based design principles that emphasize comfort, functionality, and accessibility, universities can create library environments that promote both effective learning behaviors and overall satisfaction. For instance, investments in ergonomic furniture, flexible layouts, and accessible resources could substantially boost students’ satisfaction with their learning spaces, ultimately enhancing their academic performance.

Comparison with Prior Studies

The findings of this study align with and extend previous research in several key ways. For instance, previous studies found that individual learning styles significantly affect preferences for learning spaces, which influences overall satisfaction [9, 10]. Our study not only confirms these findings but also demonstrates that these spatial preferences have an indirect effect on overall learning satisfaction through learning space satisfaction as a mediator. This mediating role highlights the importance of tailoring learning environments to meet diverse learning needs more effectively.

Moreover, Chin (2021) emphasized the shift from teacher-centered to student-centered educational environments, resulting in more diverse informal learning needs [19]. Our findings build on this by showing that informal learning needs significantly contribute to both learning space satisfaction and overall learning satisfaction, supporting the argument that modern learning spaces must cater to varied and dynamic educational requirements. The importance of flexibility and adaptability in learning space design, as highlighted by Bussell (2021) and May & Swabey (2015) [12, 13], was also confirmed in our study, underscoring the role of reconfigurable and multi-functional spaces in enhancing student satisfaction.

In comparison with recent work by Scannell (2016), who focused on acoustic environments and comfort elements [20], our study further elucidates the broader impact of learning space design, including access to resources and social interaction opportunities, on student satisfaction. Additionally, studies conducted in different educational systems, such as those by Alharbi and Alyousef (2019) in Saudi Arabia and by Kato et al. (2020) in Japan, reveal both similarities and differences in the impact of learning space design on student outcomes [22, 23]. Our findings suggest that while certain aspects of learning space satisfaction, such as flexibility and comfort, are universally valued, cultural and institutional factors may influence how students interact with and benefit from these spaces. By including international perspectives, our study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of learning space design’s role in diverse educational settings.

The cross-cultural trends in learning space utilization observed in our study are consistent with those highlighted by Marsh et al. (2006) and Brooks (2011). Marsh et al. demonstrated that key factors influencing learning satisfaction are consistent across diverse countries, indicating a degree of global generalizability [24]. Our findings support this universality while also underscoring the need for localized adaptations. For instance, Brooks found that technology-enhanced spaces improved learning outcomes across various settings [25], which is echoed in our findings that flexible and adaptable learning spaces, integrated with technological resources, contribute to improved student satisfaction.

Furthermore, some studies have shown that institutional influences can play a significant role in shaping students’ learning experiences [26, 27]. For example, innovative classroom layouts were associated with higher engagement compared to traditional settings, emphasizing the role of institutional design in supporting diverse learning activities. Our study aligns with these findings, highlighting the role of flexible, student-centered library spaces in promoting engagement and satisfaction.

Finally, our findings emphasize the importance of institutional policies in supporting effective learning space utilization. This is consistent with studies by Acedo (2012) and Cemalcilar (2010), which demonstrated that school climate and institutional practices significantly impact student satisfaction, particularly in socio-economically diverse settings [28, 29]. Our study suggests that universities should consider both universal elements of satisfaction, such as comfort and flexibility, and specific institutional and cultural needs when designing learning spaces to maximize their effectiveness.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the contributions of this study, several limitations should be noted. First, the study employed a cross-sectional survey design, which limits the ability to draw causal inferences. Future research could utilize longitudinal or experimental designs to better establish causality between learning space usage, learning satisfaction, and academic outcomes. For instance, longitudinal studies could track changes in learning satisfaction as modifications are made to library spaces over time, providing valuable insights into the long-term effects of learning space design.

Another limitation is the sample composition, which included students from various disciplines and academic stages but was limited to a single institution. Future studies should consider larger, more diverse samples across multiple institutions to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, future research could examine seasonal variations in library usage, as the frequency and nature of library use may change throughout the academic year. Furthermore, cultural factors may influence preferences for learning environments and satisfaction levels, so cross-cultural studies could provide valuable insights into how learning space design should be adapted to different educational contexts.

Lastly, while this study identified the mediating role of learning space satisfaction, future research could explore other potential mediators or moderators, such as students’ personal traits, digital literacy, or stress levels. Experimental research could also be conducted to directly assess the impact of specific design changes on student satisfaction and learning outcomes, allowing for a clearer understanding of cause-and-effect relationships. Investigating these factors could provide a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms that drive learning satisfaction and inform more targeted interventions for improving the quality of learning spaces.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides important insights into the role of university library learning spaces in shaping students’ learning satisfaction. By demonstrating that learning space satisfaction mediates the relationship between space utilization, informal learning needs, and overall learning satisfaction, the findings highlight the critical importance of well-designed, adaptable, and responsive learning environments. University libraries must go beyond their traditional roles and cater to diverse learning styles and needs, ensuring that students are provided with spaces that foster autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The practical implications are clear: investments in flexible learning spaces, ergonomic furniture, and accessible resources can substantially enhance student satisfaction, leading to improved academic engagement and success.

The limitations of this study include its cross- sectional design, which restricts causal interpretations, and the sample’s limitation to a single institution, which limits generalizability. Future research should consider longitudinal studies and more diverse samples across multiple institutions to enhance the understanding of how learning spaces affect student satisfaction over time. Additionally, exploring other potential mediators such as digital literacy or stress levels, as well as conducting experimental studies, could offer further insights into the factors influencing learning outcomes. By advancing the understanding of learning space design, future research can help to create environments that not only meet but exceed the evolving needs of students in higher education.