Introduction

Material and Methodology

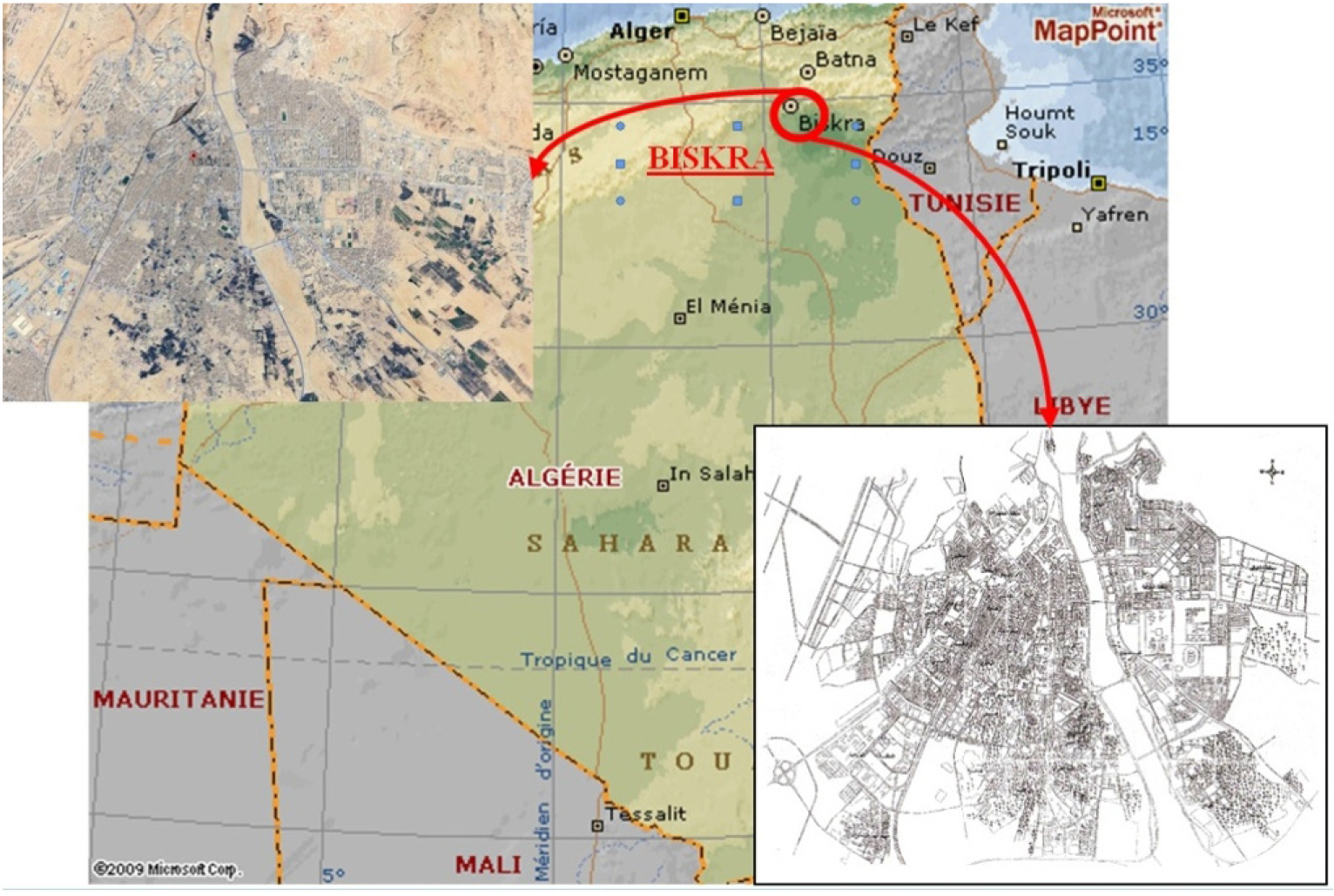

Case Study: Biskra City

Results and Analysis

Shortcomings in the Regulatory Framework Concerning Green Areas in Algeria

Quantitative and Qualitative Shortage of Green Areas in Biskra City

Causes of the Shortage and Neglect of Existing Green Areas in Biskra City

Recommendations

Conclusion

Introduction

Algeria, like many other countries, is experiencing significant urbanization and expansion. Its urban management policies have historically been influenced by French colonial legacy, prioritizing housing development in response to demographic growth and rural migration to cities [1]. This approach, however, largely overlooked non-built urban spaces (such as green spaces and public squares) under the assumption that housing would provide an optimal solution to the urban crisis. The city of Biskra exemplifies this trend among Algerian cities, with its limited green spaces in both variety and quantity [2]. These green spaces often lack essential landscaping, infrastructure, and organized plant compositions, with conditions that range from moderate to deteriorated [3].

Historically, Biskra was known for its dense palm groves, which played a multifunctional role in the social and economic life of residents serving as a key economic resource, a core aspect of urban structure, and providing notable bioclimatic benefits valued by locals [1, 2, 3, 4]. However, rapid urban sprawl and unplanned construction have led to the decline of these palm groves. Compounding this issue are poor urban planning and management practices concerning green spaces, resulting in significant neglect across regulatory, aesthetic, and climatic aspects. Consequently, urban green spaces are relegated to a low priority within urban society’s needs [5].

This situation calls for a focused examination of green spaces in Biskra, assessed against Algeria’s national urban standards. This study is guided by a critical question: Is the urban imbalance -characterized by quantitative and qualitative deficiencies in green spaces- a result of inadequacies within urban regulatory texts, or does it stem from challenges in their practical application?

Material and Methodology

The research methodology is based on a comparative and analytical approach aimed at identifying both the quantitative and qualitative deficiencies in the green spaces of Biskra [6]. To assess the quantitative deficiency, the study employs a comparative method by analyzing the surface area of green spaces according to national standards and comparing it with the actual surface area of green spaces in the city. This comparison includes all conditions (i.e., good, moderate, and deteriorating) [7]. The analysis then focuses specifically on green spaces in good condition, as these are the only areas suitable for use. Next, the ratio of green space per inhabitant in Biskra is calculated and compared with national standards. Through this approach, the study effectively demonstrates the quantitative deficit in green spaces relative to the required national norms.

To assess the qualitative deficiency in green spaces, the study uses a spatial analysis method based on multiple perspectives, utilizing checklists as outlined by Tanguy et al. (1981) [7]. Several green spaces within Biskra were selected for analysis according to their typological classification. For each space, the location was documented, and photographs were taken from both the interior and exterior, capturing key components of each space. A technical checklist was compiled, which included the following information: the name of the green area, typological classification, type classification, location, surface area, the ratio of green space per inhabitant, the estimated number of inhabitants served by the green space, the actual number of inhabitants served, the theoretical service radius, the actual service radius, and the residential area expected to be covered by the green space. Additionally, a specialized checklist was created to evaluate the components of each green space. This checklist included data on plant species (focusing on the most important types), structural elements (such as pathways, seating, trellises, and monuments), water elements (including basins, jets, and fountains), and service elements (such as sanitary facilities, prayer areas, parking spaces, commercial premises, and public lighting). The checklist also assessed the functions of the plants within the space, including their expediency, accompaniment, and aesthetic roles, each corresponding to various plant assortments.

To examine the neglect in urban management of green spaces by city officials, the study employs a quantitative research approach. This method includes techniques typically used in quantitative research, such as surveys, experiments, and structured observations, along with statistical analysis of the data. This approach is characterized by objectivity and neutrality when analyzing the situation from an external perspective [8]. A questionnaire method was chosen to survey the residents of Biskra. The objective of the survey was to assess the residents’ knowledge of green spaces, distinguishing between positive and negative knowledge based on predefined criteria. The survey also aimed to explore the respondents’ behavior toward different types of green spaces, categorizing behavior as either positive or negative. The study then examines the correlation between behavioral tendencies and several key indicators, such as cultural level, social status, material conditions, and bioclimatic factors.

In addition, interviews were conducted with urban planning authorities in Biskra. The selected method for this investigation was direct interviews with officials from municipal services, including the Urban and Environment Directorate (U.E.D.), National Office for Real Estate Promotion and Management (OPGI), and Directorate of Housing and Public Facilities (DLEP).

Case Study: Biskra City

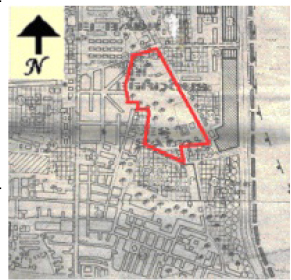

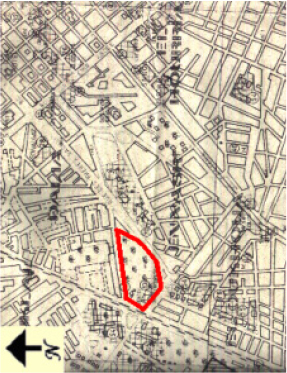

Biskra is located in the southeastern part of Algeria. It spans a revised total area of 127.55 km², primarily focusing on the core urban area of the city, distinct from the surrounding administrative region. The city consists of multiple urban and peri-urban zones, playing a pivotal role in the region (Figure 1). Biskra is considered one of the most significant cities in the area due to its attractive residential qualities compared to other urban communities [4]. It accommodates approximately 30% of the canton’s population, which reached 232,936 inhabitants in 2021, making it the most populous city in the canton. In contrast, the remaining population of the canton, totaling 401,118 inhabitants, is distributed across the other municipalities. It is worth noting that the most recent population census, conducted in 2003, recorded a population of 200,000 inhabitants [9]. This increase is attributed to the presence of essential infrastructure and services, making Biskra an attractive destination for residents seeking improved living conditions.

The city’s appeal not only influences the migration of citizens but also contributes to its rapid and unplanned urban growth, which has resulted in significant urban expansion. As of the latest data, the urban area of Biskra spans approximately 4,736 hectares, while historical analysis indicates the original settlement was an oasis system integrated within a palm grove. This grove, once constituting 90% of the city’s area, now represents merely 5%, leading to profound environmental impacts. During the colonial period, Biskra’s population did not exceed 4,000 residents. Over time, especially during the French colonization era, the city saw a gradual population increase, with native Algerians comprising 37% of the population, Europeans making up 58%, and soldiers representing 5%. During the revolution, the population doubled, including both settlers and native inhabitants. After Algeria gained independence, demographic growth became more organized, as reported by Alkama et al. [10]. (1997). The population increase has been substantial, with an annual growth rate of 3.66%, a notable figure on the international scale. This growth highlights the city’s potential for future development, particularly in terms of urban expansion, which necessitates forward-lookig planning in various sectors such as education, healthcare, services, and urban development.

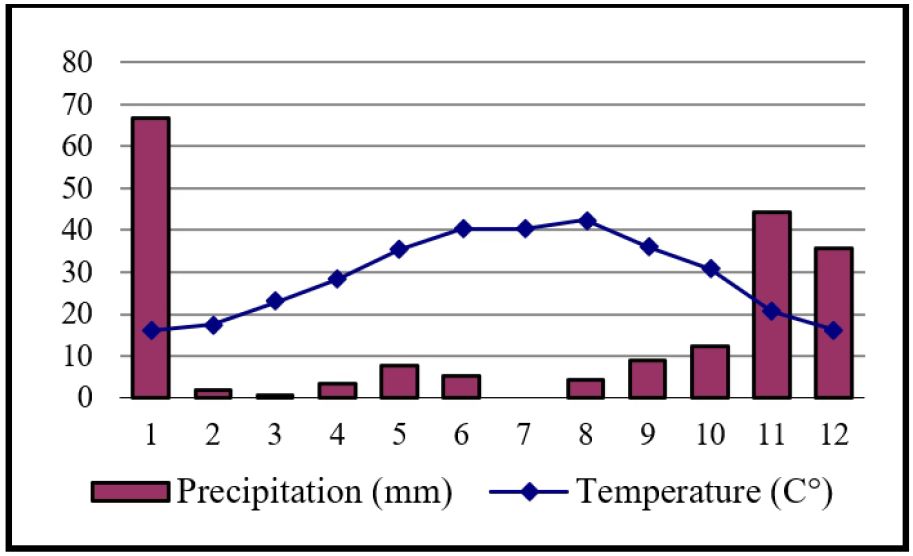

Climatically, Biskra has a dry desert climate characterized by cold, dry winters and hot summers. The Köppen-Geiger classification identifies Biskra’s climate as BWh (hot desert climate). The city experiences an annual average temperature of 21.8°C, with a wide temperature range of 7°C to 40°C over the course of the year. Precipitation remains infrequent, with an annual average of 141 mm. The highest rainfall is observed in September during intense autumn rains, which often result in mudslides, while summer months, particularly July and August, see minimal rainfall (Figure 2). These climatic patterns are further exacerbated by urbanization, which has significantly altered local meteorological conditions [11].

In terms of urban climate impacts, urban temperatures frequently exceed rural meteorological temperatures by 0.075°C to 2.71°C during the summer months, intensifying the thermal discomfort already prevalent due to the arid climate. Humidity levels in urban areas show a reduction compared to meteorological averages, typically ranging from a 3.64% decrease to a 2.14% increase. Additionally, urban wind speeds are lower by approximately 1.89 m/s, a phenomenon influenced by the city’s rapid expansion and the loss of vegetative cover, particularly the original palm groves. Evaporation rates are notably high, reaching 2,600 mm annually, while the duration of sunshine remains extensive year-round, peaking in July. Solar radiation is intense and direct, further amplifying the city’s arid conditions [4].

These climatic and urbanization dynamics emphasize the need for strategic urban planning and environmental interventions to address the challenges posed by unregulated growth, climate change, and environmental degradation [12].

Results and Analysis

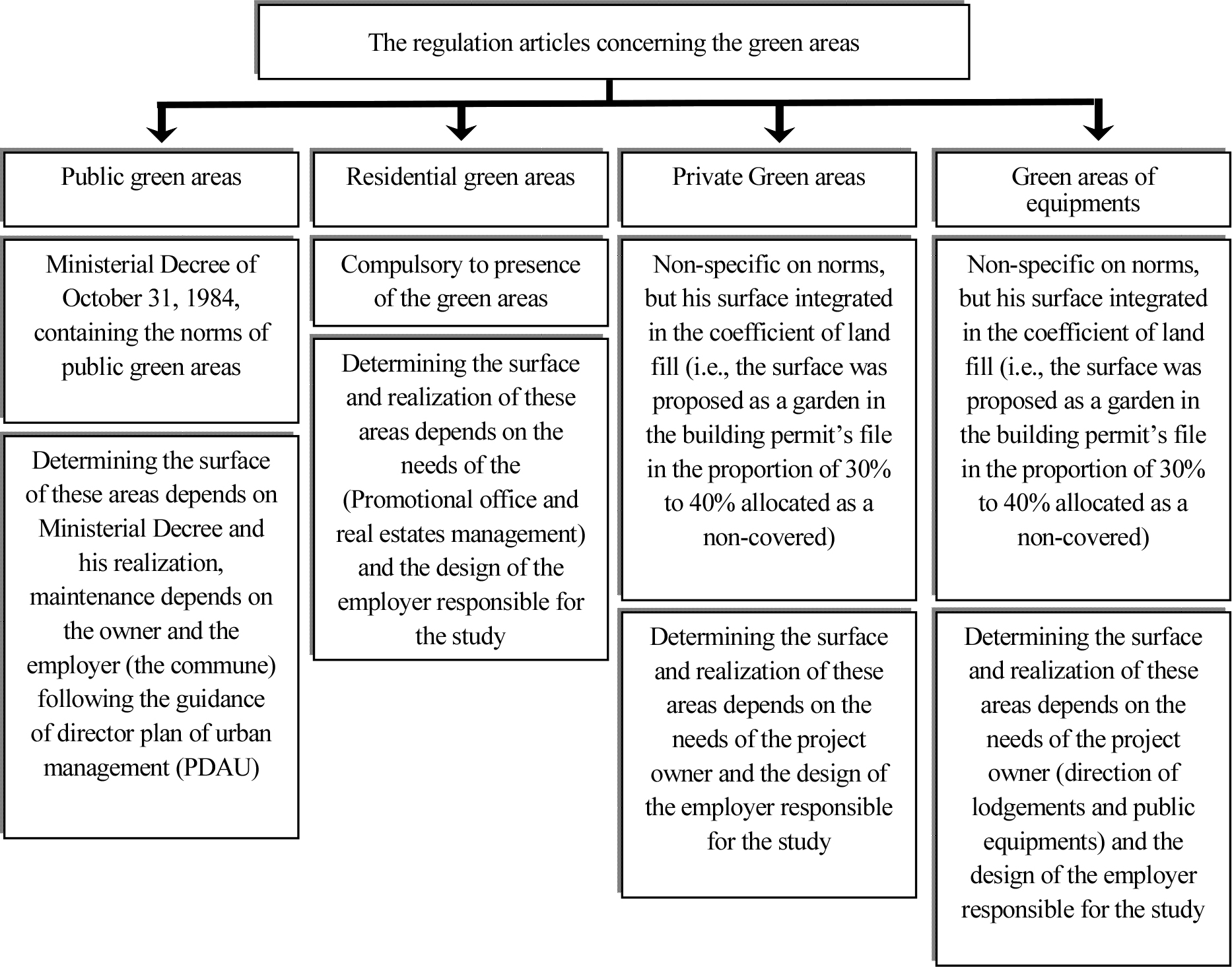

Shortcomings in the Regulatory Framework Concerning Green Areas in Algeria

Algerian urban planning policy historically prioritized housing as a rapid response to the demographic growth crises in cities [1]. This focus led to the neglect of public health and urban comfort, which are, in fact, contingent on the preservation of non-built areas. These areas were initially overlooked by urban legislation, and only later did planners begin to recognize the detrimental consequences of this oversight, including environmental hazards and adverse physical and social health outcomes. In response, national policy began to emphasize environmental protection across the country (Algeria). A comparison of Algerian and French regulations reveals several critical shortcomings [13, 14, 15, 16] :

-The generalization and centralization of the Algerian regulatory framework have resulted in significant failures, particularly hindering the effective implementation of regulations.

-There is an absence of specialized supervisory bodies, such as those responsible for the oversight of green space development.

-No formal certification exists for the approval or conformity of green areas.

-The regulations lack specific provisions for green spaces when compared to the exhaustive and detailed regulations applied to residential buildings.

-The lack of detailed regulatory texts for the maintenance and management of green spaces represents a significant gap. While laws exist protecting trees, these generally apply to forested areas outside urban environments, leaving urban trees unprotected.

-Public and residential green spaces are not explicitly required by regulation, resulting in ambiguity. The absence of mandatory standards for their inclusion in urban planning enables manipulation and underdevelopment of these spaces.

-The responsibility for the creation and maintenance of public green spaces is often seen as falling solely on local municipal councils, though the benefits of such spaces extend to the entire urban population, suggesting that broader stakeholder involvement is necessary.

-The norms for green spaces in Algeria, outlined in the ministerial decree of October 31, 1984 [17], have had little impact on urban management laws or urban planning frameworks. Not only is this decree not included in urban regeneration regulations, but its implementation is often treated as optional by urban planning authorities.

-There is a significant gap in scientific, technical, and social research conducted by experts to define green space requirements at both the local and regional levels. Such studies are essential to assess the actual needs of urban populations for green areas.

These observations suggest that Algerian urban regulations concerning green spaces are characterized by broad generalizations that create dangerous gaps. The lack of specificity in these regulatory texts, coupled with the absence of clear enforcement mechanisms, has led to significant neglect of green areas, severely undermining their effectiveness and value in urban environments.

Quantitative and Qualitative Shortage of Green Areas in Biskra City

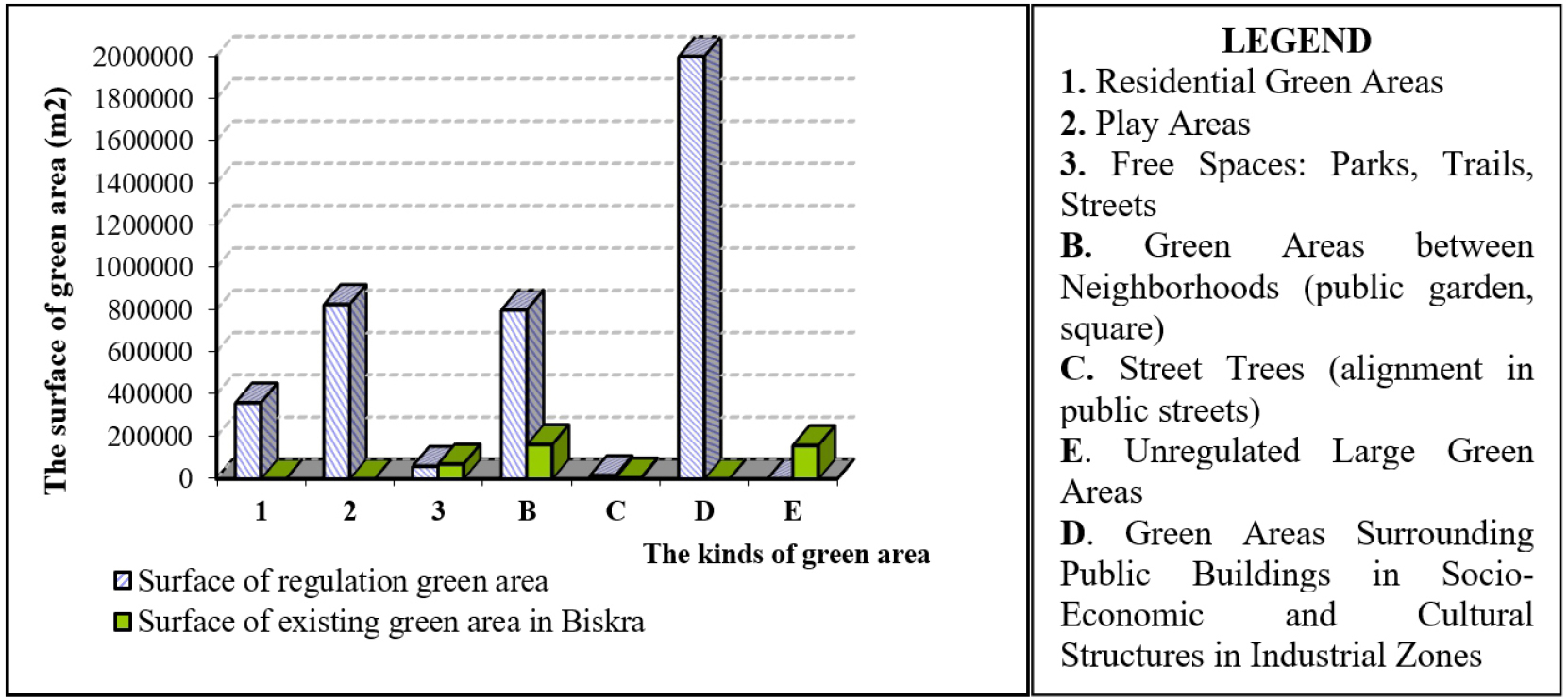

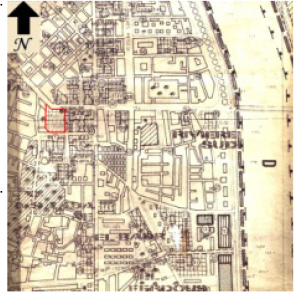

The green areas in Biskra are characterized by a significant quantitative and qualitative deficit. According to national standards, the required surface area of green spaces for the population of Biskra city in 2021, which reached 232,936 inhabitants, should have been 4,796,071.6 m², calculated based on the recommended 20.6 m² per inhabitant [18]. However, the actual available green space in the city remains critically low, amounting to only 2.45 m² per inhabitant, a figure that has not improved significantly since the earlier assessments in 2003 [9]. Furthermore, the total area of green spaces in Biskra constitutes only 5% of the total regulated urban area, which reflects a substantial degradation from its historical extent. This percentage represents just a fraction of the prescribed minimum.

The classification of green spaces in Biskra remains a critical issue. Green spaces can be divided into three categories based on their condition: fit areas, semi-fit areas, and non-fit areas. The “fit” green spaces, which are suitable for use, account for an estimated 4% of the total regulated green spaces. This limited percentage highlights the stark gap between availability and usability. Additionally, linear green spaces, such as tree-lined streets, extend over approximately 4,783 linear meters, representing 30% of the city’s paved streets [19].

The rapid urban expansion and unregulated development of Biskra have also led to the disappearance of several designated green areas from the urban fabric. These include spaces specifically intended for children, such as play yards and gardens, as well as green areas associated with public buildings serving social, economic, and cultural purposes. This loss of vegetative cover exacerbates the urban heat island effect, reduces the city’s capacity to combat desertification, and contributes to overall environmental degradation.

In light of these conditions, addressing the green space deficit in Biskra requires urgent and comprehensive planning efforts. Such efforts should include the restoration and expansion of green spaces, the introduction of sustainable landscaping practices, and the incorporation of greenery into future urban development plans.

The comparison between the required and existing green space in Biskra is illustrated in the figure below (Figure 3):

The principal green spaces in the city of Biskra fall significantly short of meeting the standards for both mass and linear green spaces. Many of these areas were not originally designated for public use or lack the essential components and coordination required for functional green spaces. Furthermore, these spaces are devoid of the appropriate vegetation types needed for their specific functions. This reflects a clear neglect in both the design and execution of public green spaces and highlights the absence of adequate regulations in Algerian planning codes regarding public green areas. Consequently, their value is diminished, their attractiveness to residents is compromised, and they are unable to fulfill their utilitarian, supportive, and aesthetic roles effectively.

The poor urban management of the city has resulted in green spaces that fail to qualify as such in any meaningful sense (Table 1). Many of these areas have deteriorated to the point of being unusable, while others have become hazardous to the community by serving as shelters for individuals with antisocial or aggressive behaviors. Moreover, certain spaces fail to align with their designated names or classifications, and others are so ineffective that their existence or absence makes little difference, as they perform none of the essential functions of green spaces.

Table 1.

The results of the quality analysis of key green areas in Biskra city

Causes of the Shortage and Neglect of Existing Green Areas in Biskra City

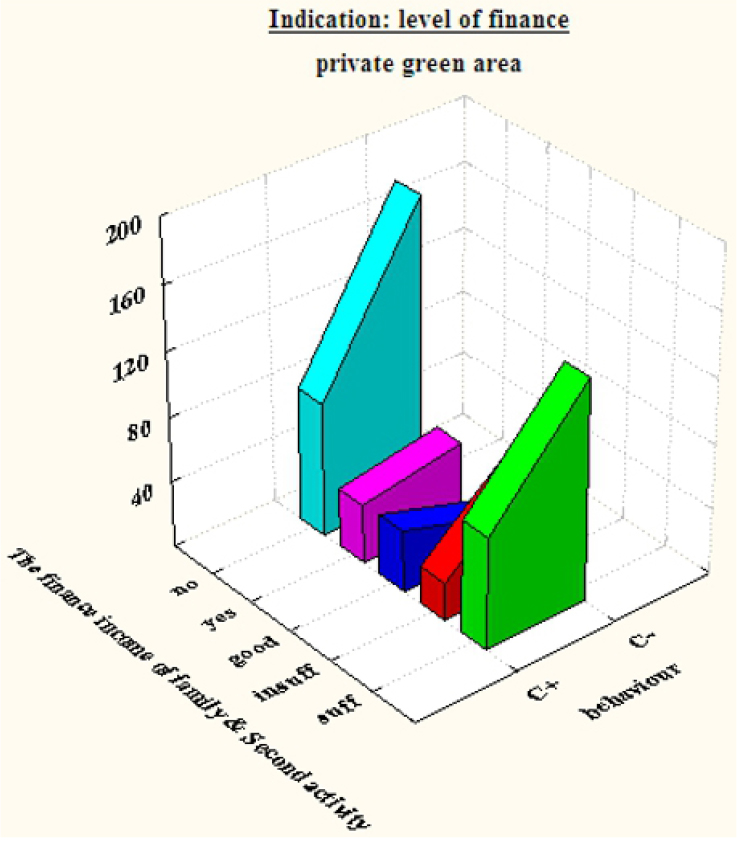

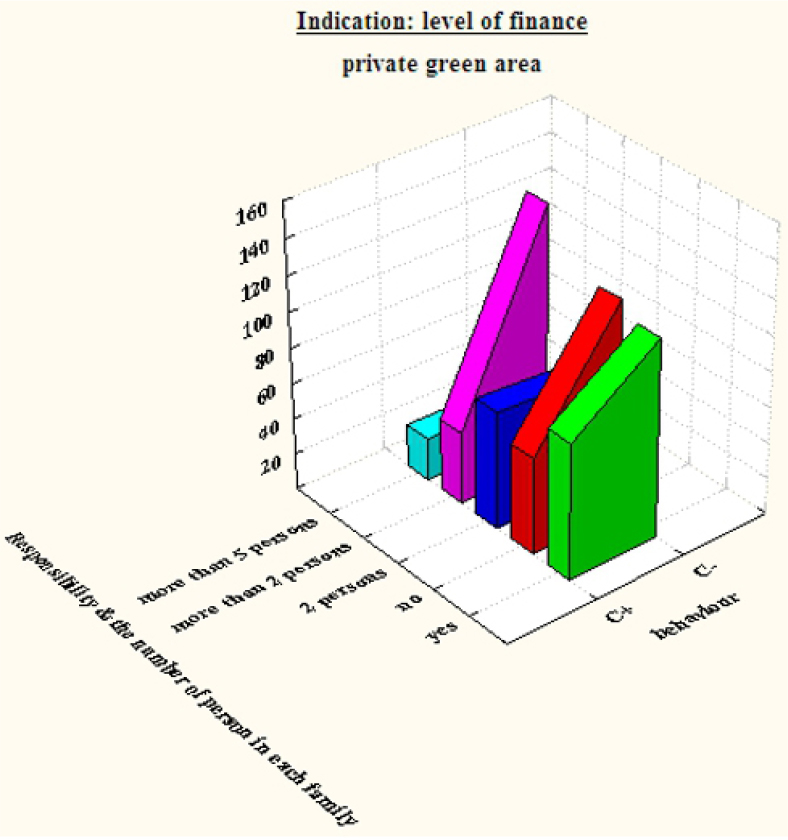

Through a questionnaire conducted with a sample of Biskra residents regarding the city’s green spaces (Table 2), it was determined that the primary factors influencing residents’ behaviors toward different types of green areas are largely shaped by financial status. The most significant indicators include family income, involvement in secondary economic activities, financial responsibilities within the family, and the household size. These variables collectively influence the financial situation of the family, which in turn determines their interaction with public and private green spaces (Figure 4, 5).

Table 2.

Key Results of the questionnaire conducted with residents of Biskra city

| Private Green Area | Semi-Public Green Area | Public Green Area | Type of Green Area |

| 36,93% | 22,82% | 60,66% | Percent of positive’s behaviour (C+) |

| 63,06% | 77,18% | 39,34% | Percent of negative’s behaviour (C-) |

When families have a higher financial level, they are more likely to afford a private garden, reducing the need for public or semi-public green areas. On the other hand, lower-income families, who do not have the means to maintain private gardens, rely heavily on public and semi-public gardens for recreational and social purposes. In these cases, however, the condition of semi-public gardens discourages families from using them. These spaces, if accessible at all, are often neglected, with their poor maintenance further contributing to their underuse. As a result, the primary recourse for lower-income families remains public gardens, which, despite their better condition, still face challenges in meeting the growing demand (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of behaviors according to variables indicating materiality level for respondents regarding private green areas

This analysis highlights the complex relationship between financial status and the use of green spaces, emphasizing how socio-economic factors directly affect the accessibility and quality of urban green areas in Biskra City.

Based on interviews conducted with representatives from various urbanization bodies in Biskra, including community services; Urban and Environment Directorate (U.E.D.), National Office for Real Estate Promotion and Management (OPGI), and Directorate of Housing and Public Facilities (DLEP), several important findings were noted. The officials reported that, according to the urban laws at the national, ministerial, and Wilaya levels, there is no direct shortage or neglect in the urban regulations governing green spaces. However, several challenges are affecting the effective implementation and management of these laws in Biskra city:

•Illegal Land Ownership: One major issue is the illegal appropriation of government-owned land designated for green space development by private individuals. This often involves unauthorized construction, which leads to legal disputes. To circumvent these issues, some urban authorities have been forced into tacitly accepting these violations, which undermines the intended urban planning goals.

•Financial and Technical Barriers: The realization of green areas is often hindered by insufficient financial resources or difficulties related to soil preparation, which further delays or complicates green space development.

•Public Mismanagement and Neglect: There is evidence of detrimental behavior by some citizens, including the destruction of plants or using green areas to graze animals. These actions exacerbate the neglect and degrade the quality of public green spaces.

•Lack of Initiative from Urban Authorities: Another contributing factor is the reluctance and lack of initiative from the responsible urban bodies in effectively executing urban plans for green spaces. This can be attributed to administrative inefficiencies or a lack of prioritization of environmental concerns in urban management.

These barriers contribute to the ongoing struggles in developing and maintaining functional, accessible green areas within Biskra city, affecting the overall quality of urban life.

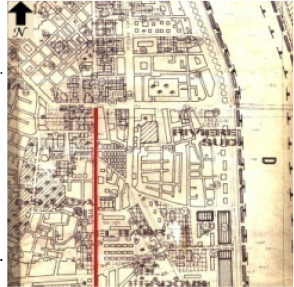

Based on interviews with urban administrative bodies, the preparation and realization of green areas in Biskra follow specific administrative processes that reveal weaknesses and flaws due to deficiencies in urban regulations, particularly those governing green spaces. These issues can be summarized as follows (Figure 6):

•Green areas around collective housing: There are two main types: social collective housing managed by National Office for Real Estate Promotion and Management (OPGI) and private and public real estate developments managed by both public and private sectors (Company for the Promotion of Family Housing EPLF and OPGI). Each type follows distinct processes for planning and execution. For state-sponsored collective housing projects, the government, represented by OPGI, selects the site for the residential complex. It then uses either a competitive bidding process or a direct agreement to select the contractor responsible for the project’s study and execution. The specifications, outlined in a cahier des charges, include details about the program and budget but rarely mention the type, size, or characteristics of green spaces. Consequently, the contractor has discretion over whether to include green spaces during project implementation. In some cases, green areas are omitted entirely or left for voluntary development by residents.

•Green areas in lot developments: After approval by the administrative council of the municipal assembly, land designated for lot developments is acquired by real estate agencies, either through purchase (for private or government-owned land) or transfer (for community-owned land). According to Executive Decree No. 91-178 (dated May 28, 1991) under Law No. 90-29 (dated December 1, 1990), a study must be conducted to define:

- The land’s boundaries and total area.

- A breakdown of land parcels and corresponding surface areas.

- Designated spaces for parking, open areas, and private servitudes.

- Specifications for green spaces and closures in the cahier des charges. Despite these requirements, the realization of green areas often remains optional or is left to voluntary citizen efforts.

•Parks and gardens: The creation of parks and gardens is based on the Land Occupation Plan. Urban sectors designated as green areas are managed by local authorities according to the approved study. However, this management is often tied to construction permits or local deliberations, leading to inconsistent enforcement.

•Public facilities and residential green spaces: The presence of green spaces is implied in the land- use plans but is not legally mandated. This regulatory gap results in their inconsistent implementation, as no specific legal provisions require the inclusion of green areas in such developments.

These findings highlight procedural and regulatory gaps, including illegal land use, inadequate financial resources, poor soil preparation, destructive behaviors by residents, and inefficiencies in project execution. These issues underscore the need for more robust regulatory frameworks and effective urban management practices to ensure the inclusion and preservation of green spaces in Biskra’s urban development.

Recommendations

The urban management strategies for green areas in Biskra should incorporate comprehensive measures to address their creation, maintenance, and regulation. This includes the following key recommendations:

•The responsibility for establishing and preserving public green areas should not rest solely with the Popular Municipal Council. All city representatives and beneficiaries must actively participate in these efforts.

•Scientific and technical studies conducted by experts are essential to accurately assess the population’s real needs for green areas.

•Establishing technical and scientific control teams specializing in assessing the condition and maintenance of plant areas is vital.

•A supervisory committee for urban bodies should be formed to oversee the various phases of developing public and semi-public green areas, ensuring compliance with national standards.

These recommendations highlight the need for regulatory frameworks specific to green areas. The suggested norms should be integrated into formal regulations, considering:

1.The selection of plant species tailored to different types of green areas, based on bio-climatic factors and the climatic characteristics of Biskra’s urban environment.

2.Satisfying the bio-climatic needs of inhabitants and specifying green area standards per citizen.

The proposed norms are bifurcated into two categories:

1.Green areas as vegetative elements: Based on a bio-climatic study, each inhabitant in Biskra requires 113.22 m² of green area to mitigate urban temperatures during summer, reducing it from 39°C to 28.33°C. This calculation considers evapotranspiration rates, atmospheric pressure changes, and urban air circulation patterns [20, 21, 22].

2.Functional needs: These are linked to specific activities, tailored for various users, and measured in terms of area per inhabitant [23, 24]. Proposed standards include:

-Residential green areas: 4.25 m²/inhabitant.

-Children’s gardens (ages 4–10): 2.75 m²/inhabitant.

-Playgrounds (ages 10+): 2.75 m²/inhabitant plus additional stadium surfaces.

-Small yards and walking pathways: 2.28 m²/inhabitant.

-Public gardens: 5.42 m²/inhabitant.

-Green areas for equipment: 22–32% of ground area, with an additional 8% for mechanical activities.

-Green areas within residential developments: 22–32% of ground area, plus 8% for ancillary activities.

These norms aim to address deficiencies in Algerian urban regulations by:

•Mandating adherence to proposed green area standards, considering vegetation as a primary focus rather than vacant spaces.

•Separating vegetation norms from functional requirements to preserve dedicated vegetation spaces.

•Ensuring green areas in all housing developments.

•Adapting standards to specific climatic zones, moving away from uniform standards.

•Prioritizing green areas for their bio-climatic functions.

•The integration of these measures into urban planning will enhance the functionality, sustainability, and ecological value of Biskra’s green areas.

Conclusion

This study on the state of green areas in Biskra City highlights a significant quantitative and qualitative deficiency in comparison to national regulatory standards. The total area of existing green spaces falls drastically short of the required minimum, even when accounting for spaces in medium or poor condition. Additionally, critical types of green spaces, such as children’s gardens, play areas, and recreational yards, are entirely absent. Some existing green spaces do not fit within any regulatory classification, reflecting a clear lack of compliance with prescribed standards.

From a qualitative perspective, the city lacks essential large-scale or linear green spaces that are publicly accessible and capable of addressing the functional, aesthetic, and environmental demands of urban life. This shortfall is aggravated by poor plant selection, limited vegetative diversity, and inadequate design and maintenance practices. Consequently, the existing green areas fail to fulfill their intended ecological, recreational, or aesthetic roles.

The underlying causes of these deficiencies are multifaceted. First, there is neglect in urban regulations, which inadequately address green spaces by prioritizing built environments over unbuilt areas. This oversight diminishes the value and effectiveness of green spaces. Second, poor implementation of regulations exacerbates the problem, with urban management bodies showing delays, insufficient budgets, and inadequate land allocation in urban development plans. These issues stem from a lack of focused studies on green space needs, coupled with insufficient motivation and initiative among responsible authorities. Finally, public engagement and awareness contribute to the issue. Questionnaires reveal disparities in how residents utilize green spaces, with public areas seeing more frequent use than semi-public ones. Private gardens, intended as uncovered residential spaces, are rare, with only one-third of residents having access to them. This gap reflects financial constraints and shortcomings in national regulations, which fail to mandate private green spaces in residential developments, leaving a regulatory loophole.

In conclusion, the neglect and inconsistency in the management of green spaces are influenced by the type of space, financial limitations, and deficiencies in urban management. Addressing these issues demands improved regulatory frameworks, more comprehensive urban planning, and enhanced public engagement in the development and maintenance of green spaces.