Introduction

Methodology

Definitions

Research process

Results

General observations

Perceived physical built environment attributes

Mental-emotional cognitive mapping

Sustainable urban spaces and society

Determinants of psychological comfort in urban outdoor environments

Psycho-comfort measurement—An essential research agenda

Conclusions

Introduction

Environmental psychology, also known as applied psychology, explores questions about human experiences in built environments by adopting a multi-level, interdisciplinary, social-ecological approach to investigate the relationships between built environment characteristics, human behavior, contextual factors, and human responses [1, 2]. Distinct from traditional psychology, environmental psychology focuses on physical settings where people live and work, examining how we interact with our environments and how these interactions influence our behavior, thereby informing urban design. In recent decades, the relationship between the built environment and psychological well-being has attracted increasing interest in the scientific community, particularly due to the adverse effects of rapid urbanization.

Human-environment interactions are shaped by various factors, leading to the development of multiple paradigms to study these dynamics [3]. For example, urban environments have been linked to diminished neural capacity for processing stress [4]. Given the prevalence of stress in modern society, understanding the restorative potential of urban spaces has become an essential area of research. Proposals suggest that incorporating natural elements can enhance the restorative qualities of urban areas [5]. Furthermore, human well-being is significantly influenced by subjective perceptions, which are shaped by visual elements such as vegetation, water, and architectural styles. These elements not only influence individual landscape preferences but also contribute to a sense of place [6, 7]. This improves understanding of place semantics, helps researchers decipher heterogeneity patterns of urban structure, and assesses the impact of urban functions [8, 9].

To date, the built environment is widely believed to influence human experiences, emotions, and cognitive states significantly. Rapidly changing urban landscapes represent a significant risk to the well-being of urban dwellers [10], with increasing evidence suggesting that living in cities can heighten the likelihood of mental health problems due to various stressors [11, 12]. Such stressors are precursors to illness and are linked to a range of health and social outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and deviant behavior [13]. Consequently, promoting public psychological well-being is a critical objective in the development of modern, human-centered urban design [14, 15]. Despite the importance of urban environmental quality to human well-being, there is currently no universally accepted conceptual framework or coherent system to effectively measure and evaluate environmental quality and its trends [16, 17].

Given the growing evidence that inadequate urbanization and transformation both positively and negatively affect psychological well-being, understanding the determinants that affect users’ psycho- comfort is critical in order to support urban space design and interventions aimed at promoting public health outcomes. Earlier studies have investigated integrating cognitive-environmental concepts and methods from disciplines beyond urban planning [18], exploring the links between place attachment and behavioral intentions [19], assessing environmental quality [17], and evaluating the therapeutic benefits of urban forests [20]. More specific investigations have addressed issues such as perceptions of crowding [21], the safety and comfort of pedestrians and cyclists [22], and the health advantages of green space exposure [23].

Although research in environmental psychology has enthusiastically explored human perceptions and the implications of built environment issues on our quality of life over the past decades, there is a lack of synthesis of existing evidence to comprehend an overall picture of the determinants of psycho-comfort in urban outdoor spaces. The interplays between features that can explain perceived experiences in urban settings remain unclear, and little is known regarding what exactly contributes to making an urban setting psychol-comfort. Furthermore, when new evidence of interactions between humans and the built environment is constantly being produced, an updated synthesis of empirical evidence is essential. This is crucial to assist urban planners and decision-makers in designing sustainable and engaging places that meet the needs of communities.

In response, this study aims to synthesize existing evidence on the relationship between built environment features and human psychological responses through a narrative review. It endeavors to consolidate our understanding of psychological experiences in urban settings by identifying key influential factors and exploring the outcomes associated with these environments. Additionally, the study integrates insights from the urban planning field to examine relevant policies and strategies, thereby promoting planning and design approaches that enhance psychological comfort in urban areas.

Methodology

Definitions

This study concentrates on the second area of environmental psychology identified by Gärling [24], which pertains to the impacts of the environment. This area refers to the effects of the physical environment on human beings, such as stress-reducing, restorative, satisfaction, or emotional responses. These concepts reflect the level of psychological comfort in outdoor spaces.

Classical theories were discussed from the standpoint of environmental conditions that reduce stress or foster well-being such as Attention Restoration Theory (ART) by Kaplan and Kaplan [25] and Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) by Ulrich [26]. Stress is a product of an individual’s judgment of their ability to cope with environmental threats using their own resources [27, 28]. Restorative urban settings are those that help individuals recover their resources, including biological, cognitive, psychological, and social [29]. Satisfaction and emotional responses refer to the psychological and emotional reactions that people have when they interact with or observe their physical surroundings. Emotional responses to the built environment are characterized by the states and expressions that convey qualities of affect, feeling, and mood that a place invokes in an individual [30]. These expressions are deeply subjective and often shaped by sensory experiences, cultural backgrounds, and personal memories associated with a location.

Research process

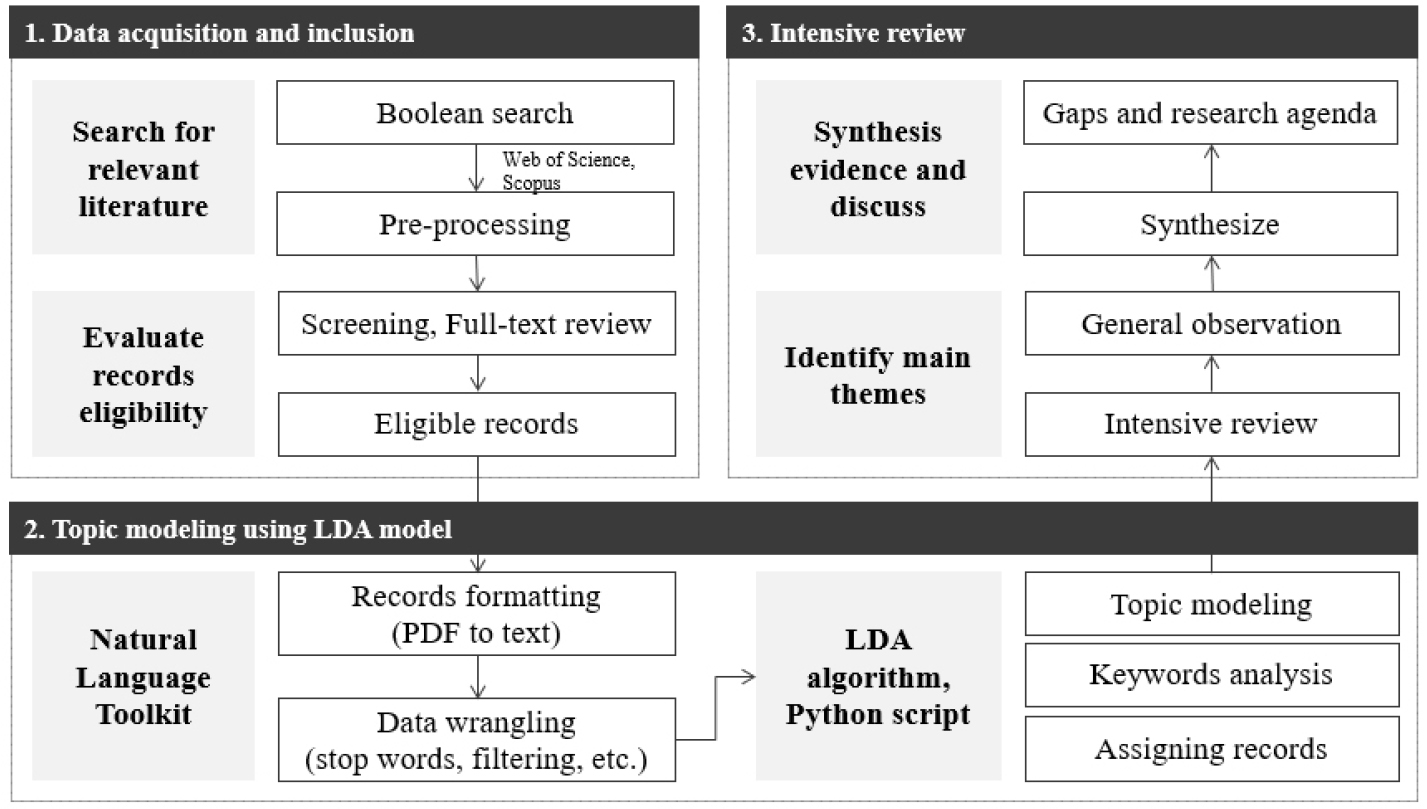

A mixed-methods approach, using narrative review and topic modeling with Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), was employed in this study. The LDA algorithm, an unsupervised machine learning technique, has become a viable assist tool to efficiently and accurately read, select, and search through large volumes of literature, with the topics identified through this rigorous, quantitative methodology rather than subjective preferences [31]. Therefore, this technique was used to initially categorize and identify the main themes of the included articles by assessing them based on the word distribution of each manuscript. This could assist scholars in speeding up the screening and categorizing process, enabling scholars to dedicate more time to in-depth review and extracting useful insights.

The research process includes three main steps: (1) data acquisition and inclusion; (2) topic modeling using LDA algorithms; and (3) intensive review, as shown in Figure 1. The first step is to identify and screen articles from well-known scientific databases, including Scopus and Web of Science. Inclusion criteria will be used to determine which records are eligible. The topic modeling technique then sought to assign each document to its proper topic based on the full-text documents of the included studies. Ultimately, the authors intensively reviewed the assigned articles based on the suggested groups by the LDA model to validate the topic assignment, taking into account their relevance to the assigned topic. Themes’ names and insights were also extracted through this procedure.

Data acquisition and inclusion

The material collection process involved two steps. First, papers were collected from respected scientific databases such as Web of Science and Scopus using relevant sets of keywords, including ‘environmental psychology’, ‘psychology’, ‘comfort’, ‘perception’, and ‘urban planning’. Second, cross-referencing was performed to ensure additional related papers were included. To be considered, a record must adhere to inclusion and exclusion criteria as shown in Table 1. After selecting papers from the database and eliminating duplicates, a total of 901 papers were manually screened (focusing on title, abstract, and keywords), resulting in 117 papers deemed suitable for a full-text review. Several papers did not meet the eligibility criteria for further analysis; consequently, a curated set of 72 publications was used for a narrative review to synthesize the findings from the literature.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for article selection

Topic modeling using LDA algorithm

After selecting the studies, the topic modeling was employed to analyze the content, facilitating the identification of key research themes. Initially, data pre-processing was required to refine the corpus, involving natural language processing techniques to parse and prepare the texts. This included converting retrieved records to plain text format and implementing several steps such as lower-casing, tokenization, removal of non-alphabetic characters, numbers, and short words (less than two characters), as well as eliminating stop words and filtering out only vocabulary words with part-of-speech tags, including nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs, using the Natural Language Toolkit package [32]. These procedures ensured the texts were clean and uniform for analysis.

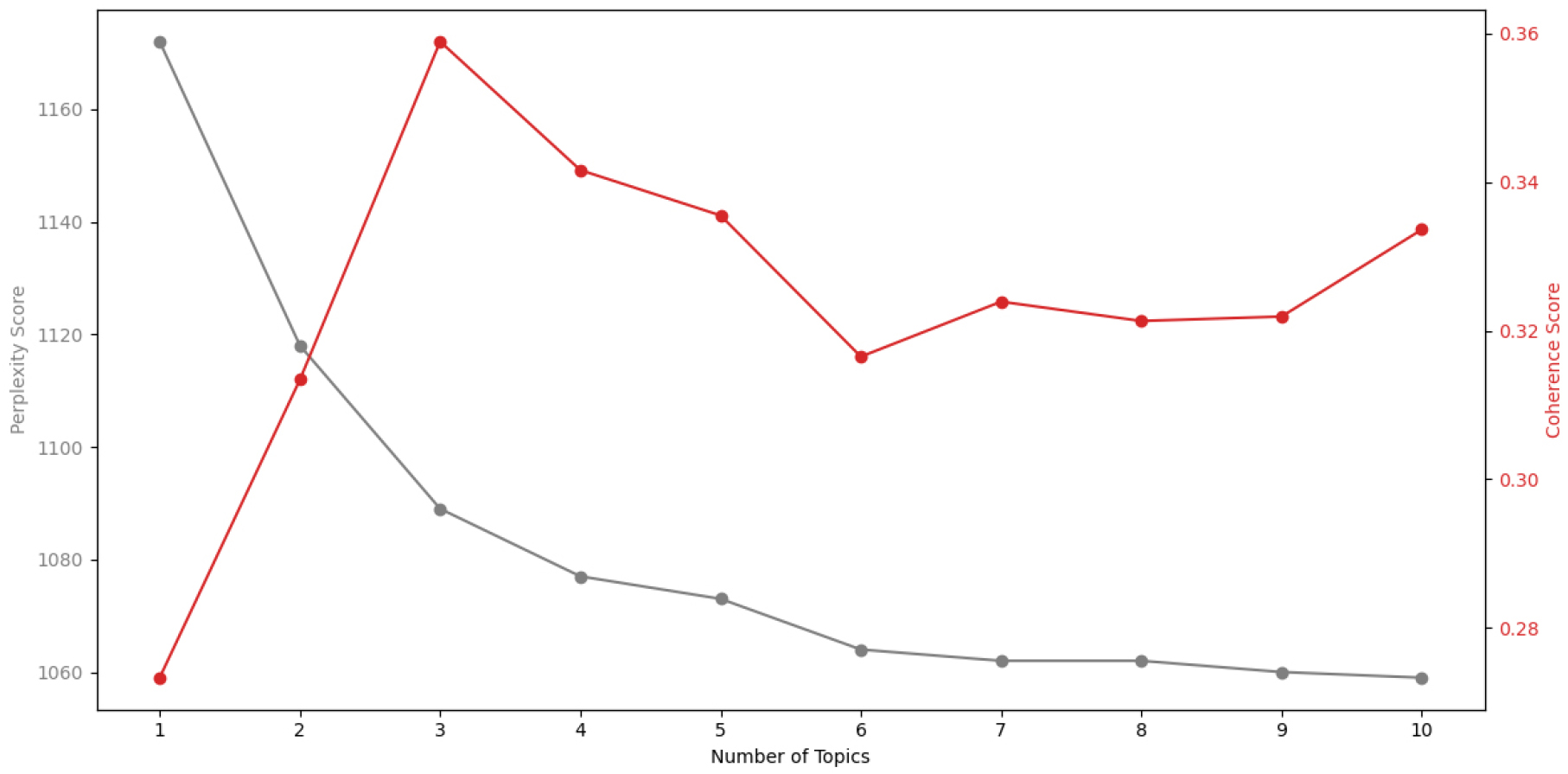

LDA, a generative probabilistic model, then analyzed the texts by treating documents as a mixture of topics, where each topic is a distribution of words [33]. To determine the optimal number of topics, metrics such as coherence and perplexity scores were employed [33, 34]. Coherence measures the semantic similarity between words within a topic for better interpretability, while perplexity evaluates the model’s predictive accuracy (Formular 1), with lower scores indicating better generalization. Where: is the likelihood of the words in document 𝑑; 𝑁 is the number of words in document; D is the total number of documents.

Due to the specific focus of this review, the maximum number of topics was defined as ten to make the review manageable. Thus, to find the optimal number of topics, a range from 1 to 10 topics with a step of 1 was tested, with the aim to minimize perplexity and maximize coherence to identify the best model [35]. It can be seen from Figure 2 that setting the number of topics to 3 resulted in the highest coherence score, at 0.3589. Besides, increasing the number of topics beyond 3 did not lead to a substantial improvement in perplexity score, at 1089. Hence, the optimal number of topics was set at three for the next steps.

Intensive review

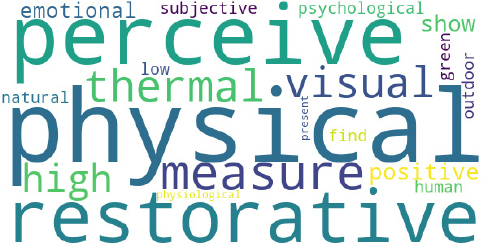

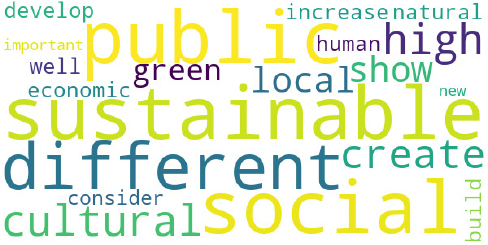

After determining the number of topics and a set of most frequent keywords for each, as shown in Table 2, the included records were thoroughly reviewed based on their respective topics. Initially, these topic themes were established through classification and word cloud analysis. Topic names and the record assignment were subsequently validated and refined through a comprehensive review process and adjustments if necessary. Ultimately, three identified topics and relevant studies are shown in Table 3. This approach is designed to enhance the organization and categorization of included articles, thereby increasing efficiency and reducing potential human errors or biases.

Table 2.

The most frequent keywords associated with three subjects determined by the LDA model

Table 3.

Topics categorizing and relevant studies

| ID | Topic name | Relevant study |

| 1 | Perceived physical built environment attributes | [7]; [30]; [39]; [40]; [41]; [42]; [44]; [45]; [46]; [47]; [48]; [49]; [51]; [52]; [53]; [54]; [55]; [56]; [57]; [58]; [59]; [60]; [61]; [62]; [93]; [105]; [106]; [107]; [108]; [109]; [110]; [111]; [112]; [113]; [114]; [115] |

| 2 | Mental-emotional cognitive mapping | [63]; [64]; [65]; [66]; [67]; [68]; [69]; [70]; [71]; [72]; [73]; [74]; [75]; [76]; [77]; [116]; [117]; [118]; [119]; [120]; [121] |

| 3 | Sustainable urban spaces and society | [79]; [80]; [81]; [82]; [83]; [84]; [85]; [86]; [87]; [88]; [89]; [90]; [91]; [122] |

Results

General observations

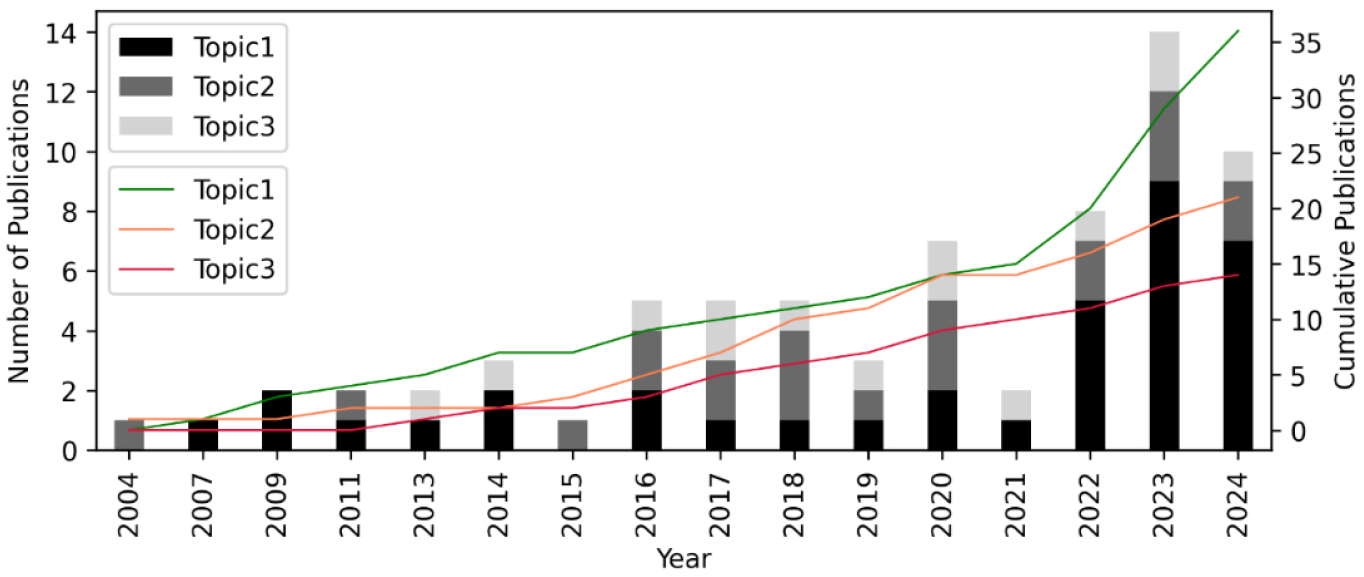

Since the built environment has a wide range of effects on human life, scholars have attempted to investigate and comprehend person-environment interactions and practices that apply this knowledge to improve contemporary cities. Overall, the environmental psychology domain has gained academic attention over the years. In Figure 3 there is a clear trend of increasing in the number of publications on this research direction. Specifically, the number of studies concerning topic 1—Perceived physical built environment attributes—rocketed after 2021, making it a dominant research theme. This could be because recent technological advancements, such as real-time tracking techniques (GPS) and ambulatory sensing, have enabled researchers to increase the empirical exploration of the relationship between urban settings and psychological reactions. Topic 2—Mental-emotional cognitive mapping—was steadily increasing, followed by Topic 3—Sustainable urban spaces and society.

Perceived physical built environment attributes

Living in cities can often correlate with mental issues, posing a significant challenge concerning psychological well-being [36]. Several facets of urban life, including both the physical and symbolic aspects of the environment, influence psychological well-being [37]. For specific, Olszewska-Guizzo, Farinha-Marques [38] categorized seven components that determine the space’s characteristics, including the landscape’s layers, landform, vegetation, light and color, compatibility, archetypal elements, and the character of peace and silence. These aspects can have either direct or indirect effects, often shaped by personal characteristics and mediated through intrapersonal psychological processes.

The natural environment, encompassing elements such as greenery, weather, and sunlight, plays a significant role in shaping human-environmental links [30, 39, 40, 41]. Even though they may be difficult or impossible to measure, humans are able to identify and use environmental cues to determine if one’s dwelling is comfortable [42]. For instance, access to natural sunlight is vital for regulating positive mood [30] and preventing conditions such as seasonal affective disorder [43]. According to Eliasson, Knez [39], favorable weather conditions, such as warm weather, low wind speed, and clear skies, significantly influence how people perceive their environment as more beautiful or calm. While this finding may hold water in cold climates, additional confirmation is required before extrapolating these insights to other climate regions. Besides, green spaces and vegetation in urban areas are crucial for promoting mental health and well-being [7]. The presence of forests or biophilic design has been consistently associated with reduced stress levels, enhanced mood, and greater overall life satisfaction [44, 45]. Despite the strong relationship between natural elements and emotional responses [46], greenery is typically limited in high-density metropolitan areas, which can lead to feelings of overcrowding and stress.

The configuration of urban spaces, including factors such as density, building layout, and the overall urban form, profoundly affects physiological responses and perceptions of citizens [47, 48, 49, 50]. High-density urban areas, while efficient in land use, can occasionally hinder restoration rates, particularly if the design does not adequately incorporate open spaces and greenery [51]. Conversely, well-planned layouts that balance building density with accessible public spaces can foster a sense of community, encourage social interaction, and enhance overall satisfaction with the environment [52]. The arrangement of buildings, amenities, and public spaces influences movement patterns, social interactions, and perceptions of safety, liveness, and comfort within an urban setting [40, 47, 51, 53]. Additionally, spaces that are both architecturally and socially characterized tend to evoke pleasant feelings such as happiness and elation, while those that are less well-designed and lived intend to evoke mild unpleasant emotions, including fatigue, boredom, and sadness [54].

Besides, design factors such as lighting, color schemes, and material choices are fundamental in influencing how people experience and connect with their environment [30, 55]. Proper lighting, particularly natural lighting, is essential for creating spaces that are both functional and comfortable [56, 57]. It affects not only visibility but also mood, productivity, and overall psychological well-being. The use of color in design further impacts human-environmental links by influencing emotions and perceptions of space; for example, bright colors may evoke positive feelings, while cool colors (blue or gray) can promote sadness, stress, and boredom [58]. Additionally, the choice of materials and textures in urban design can contribute to sensory experiences that either enhance or detract from comfort and satisfaction [47].

Beyond the tangible aspects of the urban spaces, intangible factors such as satisfaction, pleasantness, place attachment, and perceived quality of the living environment play critical roles in human-environmental connections [59, 60, 61]. The overall pleasantness of an environment, including how comfortable and safe from crime it is, contributes significantly to people’s activities such as walking [60]. Environments that offer opportunities for relaxation, whether through quiet spaces, comfortable seating, or serene views, are particularly valued for their restorative effects on mental and physical well-being [51, 53]. The relationship between the built environment features and psychological comfort also extends to the concept of place attachment, where long-term exposure to a specific environment fosters a sense of belonging and emotional connection. This connection can enhance psychological well-being by providing a sense of stability and identity. However, disruptions in this environment, such as urban redevelopment or changes in the landscape, can lead to psychological distress and a sense of loss [62]. These factors collectively shape the intricate relationship between humans and their environment, influencing not only how spaces are perceived but also how they affect psychological and emotional well-being.

Mental-emotional cognitive mapping

The mental and emotional relationship humans have with the urban environment has been of fundamental interest to urban scholars for decades [63]. Environmental psychology unfolds as an intricate exploration of how built environments influence the mental, emotional, and psychological responses of individuals. This field of study bridges the gap between architecture, urban design, and psychology, offering a holistic approach to understanding human well-being in urban settings. Historically, urban design and health have shared a connection, albeit one that primarily focuses on physical health. However, the recognition of the profound impact of urban environments on psychological well-being has gained momentum in recent years.

When assessing the quality of places, it is commonly understood that psychological well-being is subjective and differs greatly between individuals, indicating that reactions to various environments may not follow a consistent pattern. However, if such a pattern were identified, it could provide significant insights into how the spatial and social aspects of different environments affect people’s emotions and behaviors [64]. Previous studies revealed that feelings are mappable by evaluating mental and emotional responses to urban settings, focusing on understanding how individuals experience their environment [65, 66]. This involves mapping people’s sense of well-being, which fluctuates based on physical surroundings and activities. Emotional responses are shaped by various factors, including the design, functionality, and social characteristics of urban areas [67, 68]. The concept emphasizes evaluations of emotions, highlighting how urban spaces impact people’s mental states, such as stress, comfort, or enjoyment, at specific locations [65, 69].

Mapping mental and emotional responses is a crucial tool for urban planning and design, as it provides a deeper insight into how different environments affect the well-being of residents [70]. Traditional assessments of neighborhood quality often overlook these immediate and subjective experiences, relying instead on broader, generalized metrics. In contrast, feeling maps capture the dynamic and site-specific emotional experiences of users, offering a more nuanced understanding of how urban spaces function and are perceived [71]. Mapping emotions converts them into data that urbanists can readily access and analyze, facilitating improved communication between experts and the general public and promoting public discourse [72]. This data can inform decisions to improve areas that evoke negative feelings and enhance spaces that foster positive emotions, ultimately contributing to the mental health of city dwellers [73, 74].

Scholars utilize a range of tools and methods in their studies to evaluate emotional responses in urban environments from both subjective and objective perspectives. The subjective aspect of research often involves questionnaires [75], observations [68], and interviews [70] to capture individual experiences and emotions. Conversely, objective research into people’s experiences and emotions in public spaces frequently incorporates biometric techniques, measuring physiological responses such as heart and breathing rates, blood pressure, skin conductance, and body temperature [76]. Tools such as image maps, environmental cognition studies, and on-site evaluations allow researchers and urban planners to pinpoint locations that trigger specific emotional reactions. Studies conducted in cities like Oakland and San Francisco have demonstrated the effectiveness of these methods in revealing the emotional geography of urban spaces [64, 71]. Besides, Aram, Solgi [74] have developed the Aram Mental Map Analyzer (AMMA), an open- source program that equips researchers with special features and new analytical methods, enabling the conversion of mental maps into numerical data and analytical maps with enhanced accuracy and speed. Additionally, Perceived Residential Environment Quality Indicators (PREQIs) were employed to evaluate the influence of various urban features on residents’ perceptions of their surroundings [77]. The application of tools like PREQIs promotes a user-centric approach to urban problems across diverse geographic and linguistic contexts, fostering evidence-based design knowledge that informs environmental planning, design, and management. Furthermore, scholars have proposed various novel approaches to capture the nuances of psychological responses, including emotion mapping platforms [65], data mining from social media [73].

Despite its potential, the evaluation of mental and emotional responses to urban settings faces several challenges. One issue is the subjective nature of mental-emotional responses, which can be influenced by personal factors such as mood, background, and previous experiences. This variability makes it difficult to create universal solutions based solely on mental-emotional data [74]. Additionally, challenges arise in collecting sufficient and reliable data from diverse populations, especially with a physiological sensor-based approach, which tends to have a limited sample size [78]. Another gap lies in the integration of emotional data with other planning tools. While emotional maps offer valuable insights, they must be combined with spatial, social, and economic data to provide a comprehensive view of urban environments. Finally, understanding how emotions evolve over time—due to seasonal changes, development, or shifting demographics—remains an area in need of further research.

Sustainable urban spaces and society

The concept of urban life quality is evaluated across five key dimensions: physical; environmental-mobility; economic-political; social; and psychological quality of urban life [79]. These dimensions are crucial in modern cities, serving as a complex system that not only fulfills the physical and social needs of its residents but also enhances their psychological well-being [80]. The psychological quality of urban life is particularly subjective, encompassing individuals’ perceptions and evaluations of its physical, environmental, social, economic, and political facets. Hence, collecting human subjective opinions and perceptions of their surroundings could result in conflicting data, posing challenges to spatial development and quality of life [81, 82]. Thus, recognizing that an individual user’s experience is varied and persona-based is critical for urban planners, architects, and policymakers to appreciate the quality of urban space through users’ cognitive and emotional responses [83]. It is vital to address the fundamentals of psychological responses and their links, seeking to identify how these aspects might assist planners in fostering a sense of belonging in urban places and neighborhoods [84].

Research has shown that megacities, with their high concentration of human activities, increase health risks, particularly contributing to the prevalence of mental illnesses [85]. Since the psychological well-being of residents is vital, urban environments should promote safety, comfort, and a sense of community. Urban designs that promote subjective well-being can help reduce the environmental impacts of densely populated areas. To achieve this, it is critical to avoid sprawling street networks, which allow residents to engage in active movement and use urban spaces as resources that support their well-being [86]. Furthermore, avoiding overly high population densities is critical to balancing psychological impacts with social and economic benefits, as well as promoting topo-diversity in neighborhoods to create diverse local activity spaces. Furthermore, human-centric planning is an essential practice that seeks to create a spatial environment conducive to human life and sustainable development [85].

Residents’ satisfaction with their surroundings often gauges the quality of urban spaces, closely linked to their psychological well-being [87]. Factors such as access to green areas, public spaces, and local services significantly influence the residents’ perception of their living environment [80]. Thus, design strategies that incorporate these elements are more likely to result in high-quality living environments that are both sustainable and conducive to well-being. In today’s urban settings, the role of environmental psychology is critical in designing spaces that meet the physical requirements of inhabitants while also supporting their psychological health and fostering social cohesion. The integration of environmental psychology into urban planning and design is essential for creating sustainable urban spaces [88, 89, 90]. This requires a balance of environmental, social, and economic determinants, supported by innovative tools and approaches to create more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable urban environments [83, 91]. Despite existing efforts in redirecting the emphasis on urban sustainability from the city level to the development of neighborhoods, there remains a necessity to enhance methods and tools for the integration of sustainability criteria and the selection of suitable indicators in urban planning [92].

Determinants of psychological comfort in urban outdoor environments

Psychological comfort in urban outdoor spaces is a multifaceted concept shaped by various physical, environmental, and psychological factors that shape how people perceive and interact with outdoor urban spaces. These elements work together to influence an individual’s sense of security, well-being, relaxation, and satisfaction within an urban setting. The key groups of determinants are synthesized as follows:

ㆍSpatial Layout, Accessibility, and Usability: Psychological comfort is also tied to the functional and morphology aspects of urban outdoor spaces [89]. Spaces that accommodate diverse activities, from leisure to exercise, provide flexibility and cater to different needs, further enhancing psychological comfort. Additionally, ease of navigation and accessibility significantly enhance experiences in urban spaces. Spaces that are simple to navigate, well-connected, and have a clear spatial layout reduce cognitive load and increase user satisfaction [80]. Conversely, poor connectivity or complex layouts can lead to frustration, disorientation, and feelings of exclusion. Furthermore, the accessibility of recreational areas such as parks and local services, as well as pedestrian-friendly environments, encourages regular use, boosting their psychological benefits [87]. These spaces’ usability, characterized by the presence of seating and well-maintained paths, makes them engaging, thereby promoting social interactions and relaxation, all of which are essential for psychological comfort.

ㆍThermal and Physical Comfort: Physical conditions like temperature, shade, and noise significantly affect psychological comfort in urban spaces. Areas that provide shaded spaces, adequate ventilation, and protection from harsh weather enhance both physical and mental well-being, making outdoor environments more enjoyable and likely to encourage people to linger and engage. Incorporating climate-sensitive strategies into future urban design and planning initiatives is crucial, as the physical aspects of a location can be tailored to affect the local microclimate, thereby influencing how often people visit, their perceptions, and their emotional responses to the place [39]. Additionally, the overall environmental quality of an urban space deeply influences psychological comfort. Factors such as high noise levels, air pollution, or extreme temperatures can discourage the use of outdoor spaces, while clean air, minimal noise pollution, and comfortable microclimates promote longer stays and frequent visits. Thus, prioritizing environmental quality through sustainable design and climate-sensitive strategies is crucial to ensuring these spaces remain comfortable and engaging.

ㆍNatural Elements: The integration of natural elements such as trees, plants, and water features in urban spaces significantly enhances psychological comfort, drawing on the concept of biophilia—the innate human tendency to seek connections with nature [7, 45]. Environmental psychology research consistently highlights that access to nature in urban environments not only reduces stress and improves mood but also promotes relaxation [60]. Green spaces such as urban parks, gardens, and natural landscapes play a crucial role in providing physical and mental restoration [51]. They provide a restorative experience and offer mental and emotional relief from the urban built environment.

ㆍSafety and Security: Perceptions of safety are paramount for designing urban outdoor spaces [93]. Well-lit areas with clear sightlines, visible public spaces, and the presence of people generally enhance feelings of security, while poorly lit, isolated, or decaying areas can evoke fear and anxiety, causing people to perceive more stress. Ensuring the perception of safety in urban spaces is crucial, as it not only alleviates anxiety and discomfort but also fosters longer stays and more frequent use, thereby enhancing the psychological benefits of these spaces [75, 77].

ㆍSensory Experience: The sensory qualities of a space play a crucial role in influencing psychological comfort. Urban environments with excessive noise from traffic or industrial activities can elevate stress and anxiety [94], whereas spaces that incorporate calming sounds like water or wind generally enhance comfort. The quality and intensity of lighting also affect comfort levels; harsh, artificial lighting may be disorienting, while warm, natural light tends to promote a sense of well-being [55]. Tactile elements, such as smooth walkways and comfortable seating, also contribute to sensory comfort. A well-balanced sensory environment that avoids overwhelming stimuli is essential for fostering psychological comfort in urban settings [70].

ㆍAesthetics and Maintenance: The aesthetic quality of urban spaces is a critical factor in psychological comfort. Visually appealing and well-maintained outdoor environments that harmoniously blend natural and built elements, such as green spaces, water features, and art installations, promote relaxation and well-being. These aesthetically pleasing settings not only reduce stress but also heighten satisfaction among users [47]. Conversely, spaces that are neglected or cluttered with trash and graffiti can provoke stress and discomfort. The visual appeal of an area, enhanced by landscaping, architectural beauty, or vibrant public art, naturally attracts people, providing a tranquil escape from urban chaos and fostering a deeper connection with the environment. Effective design that balances these elements and provides higher levels of architectural variation can significantly enhance the overall user experience by offering both visual stimulation and comfort [49].

ㆍSocial Interaction and Inclusivity: Well-designed urban spaces that encourage social interaction while also providing flexibility in how individuals interact with their environment, enhancing a sense of connectivity [54, 84]. This includes a thoughtful design that integrates the space with its surroundings through continuity and seamless transitions between areas, such as moving from a bustling street into a tranquil park. Additionally, public spaces like parks, plazas, and markets that facilitate social encounters help foster a sense of community and belonging. An inclusive design that accommodates diverse groups, including families, the elderly, and people with disabilities, ensures that everyone can feel welcome and comfortable. Such environments promote social cohesion and reduce feelings of loneliness, but they also contribute to overall emotional well-being by encouraging positive social exchanges and reducing social isolation.

Psycho-comfort measurement—An essential research agenda

The increasing density, crowding, and chaos in cities, intensified by rapid urbanization and climate change, increasingly threaten the physical and mental well-being of urban residents [95, 96, 97]. Factors like air pollution and the urban heat island effect are significantly impacting human health [98]. Researchers have pointed out the substantial risks of heat stress and environmental pressures on human sensitivity to weather conditions [99, 100]. In response, the ‘bio-comfort’ metrics were developed to evaluate conditions adversely affecting urban residents’ physical health [101, 102, 103]. However, mental health, which is equally important, lacks a comparable ‘psycho-comfort’ metric, primarily due to the difficulties in consistently measuring spatial perception [74]. As ‘psycho-comfort’ receives less focus than ‘bio-comfort’, developing a standardized measure for its subjective aspects remains a significant challenge.

Terms like urban environmental quality, livability, quality of life, and sustainability are prevalent in public discourse and central to research, policy-making, and urban development. However, their application in research and policy contexts is seldom uniform [17]. Furthermore, the psychological dimension is inherently subjective, encompassing individual assessments and perceptions of the physical, environmental, social, economic, and political aspects of urban environments. This subjective nature presents a challenge for researchers attempting to understand the connections between objective urban features and subjective evaluations of these environments [79]. Therefore, it is vital to comprehensively examine the psychological responses to urban environment stimuli to understand better the effects of urban features, design, and planning on mental and emotional wellness. Developing a ‘psycho-comfort’ metric could enhance our grasp of how environmental factors influence psychological well-being. Comfort arises when the mind recognizes and interprets stimuli as either comfortable or uncomfortable [42]. The concept of a psycho-comfort threshold encompasses the range of mental and psychological states—both positive and negative—that individuals experience in an environment, influenced by factors such as spatial structure, aesthetics, noise levels, perceived safety, crowding, access to nature, and sensory experiences. In the context of urban design and public space research, which prioritizes place quality and social interactions within urban environments, it is crucial to validate how quantitative data correlates with environmental quality and user behavior [104].

Recognizing psycho-comfort thresholds is crucial for urban planners to design spaces that support not just physical but also mental health [67]. Environments that are psycho-comfortable can alleviate anxiety, enhance mood, and promote overall well-being. Moreover, these comfortable settings encourage outdoor activities, socialization, and community engagement, enhancing feelings of belonging and satisfaction. In urban planning, integrating psycho-comfort with bio-comfort is critical for creating comprehensive, user-centric outdoor environments that address both physical and psychological needs.

Conclusions

The relationship between the built environment and psychological well-being has become a focal point of scientific inquiry, especially in the context of rapid urbanization and its dual impact—both positive and negative—on mental health. This study contributes to this growing body of research by synthesizing evidence on how features of the built environment influence psychological responses, with the ultimate goal of guiding urban planning and design to foster public well-being. By identifying key themes—Perceived Physical Built Environment Attributes, Mental-Emotional Cognitive Mapping, and Sustainable Urban Spaces and Society—this study provides a nuanced understanding of how urban design can affect psychological experiences and emotions, thereby promoting user comfort and satisfaction.

The findings of this study carry significant implications for urban planning, policy-making, and interdisciplinary research. First, they underscore the importance of incorporating psychological well-being as a key consideration in urban design, moving beyond purely functional or aesthetic priorities. The evidence highlights the need to create spaces that not only meet physical needs but also promote mental and emotional health by addressing key environmental stressors and enhancing restorative features. Second, the study advocates for a more holistic approach to urban development, where the built environment is seen as an integral component of a broader social-ecological system. Urban planners and policymakers are encouraged to consider factors such as place attachment, perceived safety, and sensory engagement in their designs. By doing so, cities can become more inclusive and supportive of diverse communities, aligning with global sustainability goals such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Lastly, despite numerous studies investigating the impact of urban environmental stimuli on human mental-emotional responses, the subjective nature of the psychological aspect leads to a lack of uniformity in the measurements. A comprehensive ‘psycho-comfort’ measurement is essential to assist urbanists in grasping how environmental factors influence psychological well-being and designing spaces that support not just physical but also mental health. This would be a fruitful direction for further work but necessitates the need for interdisciplinary research and comprehensive evaluations to assess the effects of urban environments on human psychological comfort and well-being.

We acknowledge some limitations of this work that can be improved in the future. This study may not encompass all existing literature due to the lack of consideration for studies from other scientific databases such as PubMed or IEEE Xplore. Furthermore, even though we utilized topic modeling to facilitate the review process, we may still encounter human errors during the intensive review phase. Future research should aim to address these gaps by incorporating a broader range of literature, including gray literature and studies from diverse disciplines. Expanding the scope of analysis to include longitudinal studies and varied geographic contexts would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how urban environments influence psychological well-being over time. Furthermore, the development of standardized, interdisciplinary frameworks for measuring psycho-comfort is crucial. Such frameworks should integrate subjective and objective metrics, ensuring consistency and comparability across studies.